As told by Elaine Pearson

Large bruises were still visible on Nika's face and body. The week before, she had been brutally beaten by municipal security guards in a public park. She had been talking on her cell phone and didn't hear them when they told her to "move."

One guard kicked her, then three others joined in - two held her hands, while two beat her with bamboo sticks and their radio. Nika tried to fight back, but was overpowered. Police officers walked by and did nothing. Her clothes were ripped. The flogging lasted for about 30 minutes.

Nika, 28, is a sex worker. She sounded both fiery and frustrated as she told me how a legal aid organization said it couldn't help her if she didn't have witnesses. Plenty of people - other sex workers and motorcycle taxi drivers - witnessed the attack, but they feared police retaliation if they came forward.

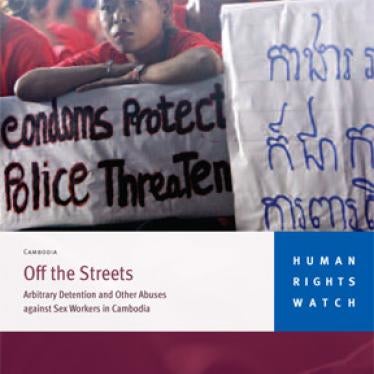

Human Rights Watch recently spoke with more than 90 female and transgender sex workers who said that police had beaten them with their fists, sticks, and electronic shock batons. Several said officers raped them while they were in police detention. Every single sex worker we spoke with said the police demanded bribes or stole money from them. Some officers demanded sex.

"I feel sad and disappointed," said Nika, whose only experience with the police or municipal guards has been officers beating or chasing her. "I was seriously beaten [by the guards]. I know no one will help me. I was scared. I want to tell you this because I want to make every effort to stop abuse."

In 2008, Cambodia passed a law on "The Suppression of Human Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation." While the intention was to protect people who have been forced into sex work, Human Rights Watch found little evidence that this has happened, or that prosecutions for trafficking have been pursued. Instead, officers were more likely to use the law as a convenient excuse to continue to exploit and abuse sex workers, many of whom entered sex work because of poverty and lack of economic opportunities.

For example, provisions like the one outlawing "solicitation" make it possible for corrupt police officers to harass nearly all sex workers who ply their trade, without facing prosecution.

The law's definition of what constitutes procurement of women is so vague that it could lead to criminalization of advocacy and outreach activities by sex worker groups and those who support them.

Many sex workers are arrested in regular police sweeps of Phnom Penh's streets and parks. Some are released; some, including children or those who have been trafficked, are sent to a government office for processing.

But some sex workers are forced into an abysmal government-run center, Prey Speu, or others like it. In 2008, Cambodian rights groups and the United Nation's human rights office in Phnom Penh documented suspicious deaths, rape, and torture in Prey Speu. The Cambodian government responded by saying it would stop sending sex workers there. But as recently as last June, sex workers reported being detained - and abused - in Prey Speu.

On top of these abuses, fear of arrest and detention forces sex workers underground, making outreach to find those who have been trafficked or on issues such as HIV/AIDS more difficult.

Since releasing our report, Human Rights Watch has held meetings with the US State Department, select members of the US Congress and Senate, and USAID, as the United States is one of Cambodia's largest donors and a major supporter of its anti-trafficking efforts. We want countries that finance anti-trafficking activities in Cambodia, such as police training, to pressure Cambodia to hold their police forces accountable, and to stop the abuse.

We ultimately want the Cambodian government to suspend the legal provision on solicitation, until the issue of police abuse is resolved. Officers who abuse sex workers should be held accountable, and the government should close abusive detention centers like Prey Speu.