When I took an internship at Human Rights Watch for the summer, I thought I would spend it at a desk researching international human rights law. But last week I unexpectedly found myself at Guantanamo Bay -- fortunately not as a detainee, but to observe a hearing in the case against Noor Uthman Muhammed.

Noor Uthman Muhammed (known simply as Noor), a Sudanese national taken into custody in Pakistan, is charged with conspiracy and providing material support for terrorism. Both charges are included in the Military Commissions Act of 2009, which the Obama administration said would fix the flawed Bush-era military commissions, but neither charge is a traditional war crime under the laws of armed conflict.

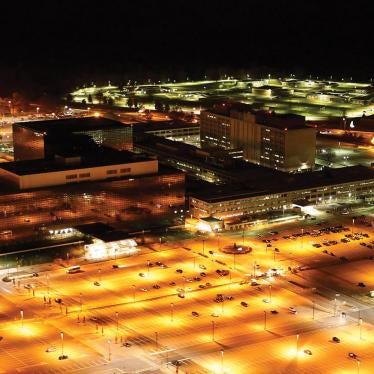

Arriving at Guantanamo on Monday, June 28, the three other nongovernmental organization monitors and I were greeted by a military escort, who took us to the place we would call home for the next four days -- a tent in what is called Camp Justice. From the window of my tent, beyond a chain-link fence and coils of razor wire, I could see the courthouse. The monitors fly down to Guantanamo along with the prosecutors, defense lawyers, courtroom support staff and journalists. Since there are certain things the lawyers can only do at Guantanamo (including, for the defense lawyers, meeting with their clients), the rest of us waited around for two days, until the hearing on Wednesday.

During those two days, every move we made outside of Camp Justice was monitored by a military escort. Wherever we went we were required to move as a team. The US military has legitimate security concerns at Guantanamo, but even our escorts seemed to recognize how irrational some of the rules are. When we called a defendant a "prisoner," our escort quickly told us that military personnel must call them "detainees." I asked another escort where the camps are with the detainees. He said that information is only revealed on a need-to-know basis, and then added that I could Google it. "I'm sure it's on the internet," he said.

On the day of the hearing, we passed through multiple security checks before being allowed into the courtroom. Our escort's name was no longer on his uniform. All the soldiers had numbers or titles in place of their names. We were told that there was a seating chart, and NGO monitors were placed in the back corner. The journalists sat at the opposite end of the courtroom, with a rope separating them from other observers.

The courtroom was empty when we arrived, but the lawyers eventually filed in. The judge entered, and we all rose, but the defendant was still not present. As I glanced over the press section, another NGO observer pointed out that Carol Rosenberg, a journalist with the Miami Herald who has covered every military commission, was also absent. The government had barred her and three Canadian journalists from attending further commissions because they had published the name of a government witness even though his name has been publicly available for years.

The government lawyer, Navy Lieutenant Commander Arthur Gaston, a tall uniformed man with a regulation haircut, announced that the defendant was not present. The parties were aware of Noor's refusal to attend the hearing and had stipulated that the absence was voluntary, so the hearing could continue.

The judge, Navy Captain Moira Modzelewski, a soft-spoken woman, swiftly moved to the primary issue of the hearing -- the defense's request for the government to pay for a specific psychiatric expert, Dr. Jess Ghannam, to examine Noor. While the military commission rules allow for the appointment of psychiatric experts to determine if a defendant is legally competent -- something commonly done in federal court as well -- the defense had different reasons for requesting a psychiatrist.

Navy Commander Katharine Doxakis, the lawyer arguing for the defense, laid out several reasons, primarily to determine whether Noor had been subjected to ill-treatment during the interrogations in which he made statements, 17 of which the government plans to base its case on. In a standard criminal case, a coerced statement cannot be used, in part because such statements are unreliable. But surprisingly, under the military commission rules, a coerced statement is not automatically considered involuntary. It is up to the military judge to decide that.

In addition to its argument before the commission, the defense submitted a written brief to the judge that the prosecution is not allowed to see. The defense said the brief included arguments that went to the defense's theory of the case, and therefore need not be shown to the prosecution. The government lawyer countered that the request should not be approved because the defense had not shown that it was necessary for Noor to be examined by Dr. Ghannam. He argued that the defense must provide more information to show necessity, even if that information goes to the defense's theory of the case and they do not want to disclose it to the prosecution at this point. It is ironic that the government focused its argument on transparency given the vast amount of classified information it will use in this case -- information that will never be shared with the defendant.

The judge asked if there were any other issues to address before the recess. I assumed she meant lunch, but she meant the end of the hearing. Noor has spent more than eight years in detention and has waited more than two months in his cell since his last hearing to get one issue before the judge, an issue that would probably not need to be addressed if his trial was in federal court.

The judge will rule on whether an independent psychiatrist can examine Noor before the commission has determined whether it has jurisdiction over him. That issue will not be taken up until his next hearing, scheduled for late-September.

As the closing of Guantanamo becomes a fading priority, it is business as usual at the military commissions.