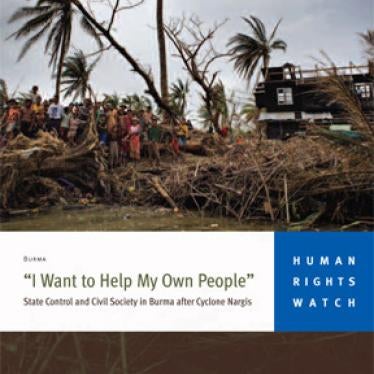

BANGKOK--Two years ago, in early May 2008, Cyclone Nargis destroyed much of Burma's Irrawaddy Delta and parts of its former capital city Rangoon with 160 kilometer winds and a massive storm surge, killing more than 140,000 people. The ruling military junta, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) then failed to help, prioritizing their iron-clad grip on the country over the well-being of the Burmese people. They refused visas to international emergency relief workers, set up roadblocks to stall and in some cases seize aid, and expelled foreign reporters who were bringing the desperate situation to light. Only after the completion of the SPDC's charade referendum on a new constitution did they finally allow international aid to reach the storm victims.

But thousands of ordinary Burmese didn't wait. Many organized friends and colleagues, pooled their resources, and went to the affected areas to help distribute food and water, build shelters, tend to the injured, bury the dead, and assist survivors rebuild. They were myriad groups of private citizens such as engineers, doctors, rock stars, businessmen, travel agents, religious leaders, and others from all over in Burma who came to help any way they could.

In those desperate days after the cyclone, these brave Burmese thumbed their noses at their repressive government frozen by its inability to switch from brutality to compassion. One Burmese aid worker remarked: "It was Cyclone Nargis which created the space for us to engage in humanitarian work, not the government."

Hundreds of new ad-hoc civil society groups bloomed and grew, and networked to sustain the response. But there were limits, again set out by the SPDC: the military punished those who helped but then felt compelled to criticize the government's poor response. The famous comedian Zargana and twenty other community aid workers were arrested, hit with trumped up charges, and thrown into prison with long sentences - Zargana got 35 years - where they continue to languish, largely forgotten.

Optimism flourished in the months after the cyclone, with some foreign observers believing growing international aid response would help normalize aid relations and lead to a deeper understanding with SPDC leaders about the need for international assistance and expertise in development. The Tripartite Core Group of the SPDC, UN and ASEAN was presented as a model to expand operations throughout Burma.

Two years on, those hopes have not been realized. Humanitarian aid workers inside Burma told Human Rights Watch the major dividends from the Cyclone Nargis have not translated into expanded access for assistance in the rest of the country. One foreign aid worker remarked that "if the generals just took their boots off people's throats, Burma [and its development] would take off," he said.

Burma remains a development basket-case. It has the worst maternal mortality rate in Asia after Afghanistan. One-third of the country lives below the poverty line. The SPDC's limitations on operations of aid agencies contribute to Burma's status as one of the lowest per capita foreign aid recipients in the world, with only US$2.80 per capita. By comparison, neighboring Laos receives close US$50. Major health and livelihood challenges remain in the central dry zone of Burma, and in former opium growing areas of Shan state. Severe malnutrition affects many of the one million stateless Rohingya Muslims in Northern Arakan state. In eastern Burma, the world's longest running civil war has displaced millions, and access by aid workers is constrained by government restrictions, fighting and landmines. Major humanitarian aid donors like the European Union and Australia balk at finding new ways to deliver cross border assistance to conflict zones, despite the urgent needs.

Meanwhile, the SPDC is estimated to hold more than US$5 billion in foreign reserves and receives an estimated US$150 million per month in revenues from natural gas exports, but it hardly shares this largesse with its people. What limited assistance the Burmese government does provide is non-transparent, and channeled through its surrogates and contracts awarded to politically connected companies close to the military, such as Asia World, Htoo Trading, and Max Myanmar; all three companies are on Western sanctions lists. The regime spends most of the country's wealth on military hardware, infrastructure, and building the new capital city at Naypyidaw. The international community needs to better calibrate and coordinate targeted financial sanctions against the regime leadership and their close business associates to exert pressure on this state perpetrated perfidy. Only increased pressure on the leadership's interests and income will compel them to observe more responsible distribution of resources.

The real hope for expanding humanitarian space in the country rests with Burmese civil society itself. International donors and UN agencies should find ways to increasingly support their efforts, while ensuring that assistance does not benefit the military, or the companies of military families and favored tycoons. The people of Burma are the real hope, and the only solution, to their country's problems.

David Scott Mathieson is Burma researcher for Human Rights Watch