Around the world ordinary civilian courts deal with the most complex of terrorism cases, where judges can draw on years of precedent to sort out basic issues such as jurisdiction and access to evidence. Sticking with the military commissions means that the United States risks having its own system of justice being put on trial even as it pursues justice for the terrible crimes of September 11, 2001.

Being on the Guantanamo Bay naval base is an experience in itself, part rocky beachfront, part small-town America. It’s a balmy Caribbean February. The observers, together with the media, are housed on the west side of the bay, which separates us from the main base, the stores and residences, and the inaccessible detention facilities. To get to the commission hearings we have to cross the bay itself - usually in fast gunboats. The base is much larger than I expected, with McDonald's, Starbucks and other amenities to make it feel like home for the military personnel. One distant gate marks the boundary of the base with Castro’s Cuba. Signs around the base warn that anyone harming the rare iguanas found here faces a $10,000 (£5,000) fine. There are no such signs concerning the protection of the detainees.

I spent a week in Guantanamo to observe for Human Rights Watch hearings in the only two criminal cases presently being heard there: those of Omar Khadr, a Canadian, and Salim Hamdan, a Yemeni once a driver and bodyguard to Osama bin Laden. Both cases are in pretrial hearings.

Six years after the first detainees were brought to Guantanamo, there has still not been a single trial.

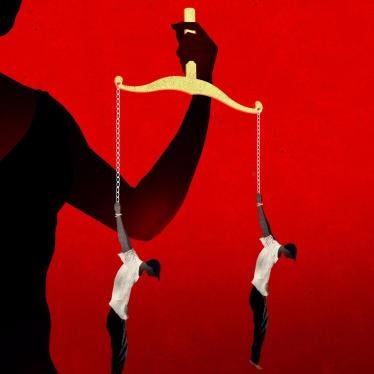

There are several reasons but the key is the initial decision of the Bush Administration not to pursue cases in a regular US federal court, or even in a court martial, but before special military commissions.

Last Monday the US Government announced that six alleged key conspirators of September 11, including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind, would be charged with various offences and face the death penalty. But that still leaves more than 260 people without any criminal charges. They are simply being detained.

In 2006 the US Supreme Court in Hamdan’s case found the military commissions at Guantanamo to be illegal because they permitted prosecutions in violation of the Geneva Conventions and were not in conformity with the US Code of Military Justice. In response, the US Congress passed legislation to create a new structure of military commissions.

The courtroom at Guantanamo was created for the commissions and a permanent building is in the works. However, it’s not just the buildings but an entire justice system that is being created from scratch. It is therefore not surprising that many of the pretrial arguments have been about fundamental questions of jurisdiction and what crimes, and what suspects, the commissions can deal with. The US Government is claiming that this novel system of justice cannot rely on any other body of established law and thus the commissions have no precedents to draw on in deciding highly complex issues.

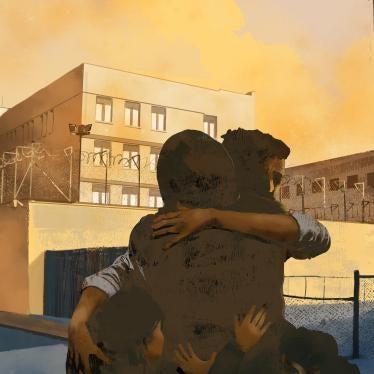

One of these is the Government’s oft-repeated arguments that Guantanamo detainees have no rights under the US Constitution or international law. For example, in the case of Omar Khadr, the Government believes that the commission can try a child soldier without any regard for his juvenile status. Khadr was 15 when taken prisoner during a firefight in Afghanistan with US soldiers in which he is alleged to have killed an American.

International law places a duty on states to treat juvenile soldiers with an eye to rehabilitating them. Unlike the couple of other children held at Guantanamo, the US has never treated Khadr as a child, for instance, by housing him in quarters separate from adults.

At the pretrial hearing the Government argued that the military commissions not only apply to juveniles but require them to be treated as adults. Thus, Khadr will be tried without any specialist juvenile judge, despite the trial focusing on his actions and words between the ages of ten (the age he is alleged to have been forced to join al-Qaeda) and 15. Indeed, the Government contends that the commissions could apply the death penalty against juveniles, though it has just chosen not to in Khadr’s case. The juvenile death penalty has been abolished in the United States.

These fundamental problems have emerged in the first two, supposedly simple, cases. Now the US is attempting to use this ad hoc system of justice to prosecute those accused of planning and executing the September 11 attacks and other major crimes. Among a multitude of issues, the commissions will need to address whether evidence obtained through coercive interrogation — including torture — can be admitted.

The issue of criminal trials is, of course, separate from the legality of the detention of the 275 people who remain incarcerated at Guantanamo. Until this month the number of Guantanamo detainees charged with criminal offences was precisely three. (The third person charged, Mohammed Jawad, has not yet had a hearing.)

Only one prisoner, David Hicks, has been convicted. He agreed to a guilty plea after nearly six years of detention allowing him to return home to Australia and serve a nine-month prison sentence.

For the criminal cases, there remains a relatively simple solution. Rather than continue to construct a new system of justice, they should be transferred to US federal courts. Around the world ordinary civilian courts deal with the most complex of terrorism cases, where judges can draw on years of precedent to sort out basic issues such as jurisdiction and access to evidence. Sticking with the military commissions means that the United States risks having its own system of justice being put on trial even as it pursues justice for the terrible crimes of September 11, 2001.