Guantanamo Bay in November is rocky, sunny and hot. The military commission is located in the old naval base headquarters, a light-ochre building atop a windswept hill. A badge and a military escort get you through the several checkpoints.

About 80 black-cushioned chairs in three rows are provided for the spectators - US government and military officials, journalists and trial observers. Beyond a wooden railing, the prosecutors and the defence counsel fill two tables. The members of the commission, in uniform not robes, are behind a raised judicial bench beneath flags of the US and the four military services.

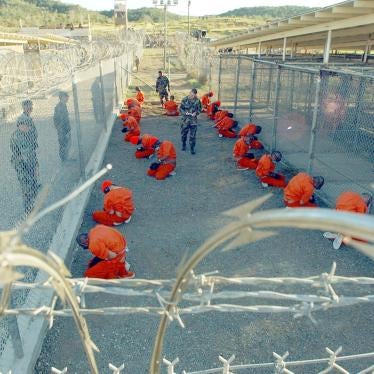

I attended the trial of David Hicks, an Australian suspected of terrorism. He and the others who face charges before the US military commissions are in nowhere near the same league as the leaders of the Third Reich who faced the Nuremburg tribunals. But the impact of the commissions on the development of international justice may be no less important.

Defence and prosecution lawyers argued fundamental and sometimes novel issues. Are unlawful acts by "unprivileged" combatants (civilians who take up arms) war crimes? Does international law recognise as a criminal offence "conspiracy to commit a war crime"? Can a person with no allegiance to the US be prosecuted for "aiding the enemy"?

Yet only one of the three commission members had legal training. And they struggled even with basic concepts of criminal law. One did not seem to understand why a law imposed ex post facto (after the crime took place) posed a problem. Another saw no difficulty in bringing charges that did not specify a clear criminal offence.

Even worse was the attitude of the commission members towards the adversarial process. All three are senior military officers with distinguished records. They reacted to defence challenges as you would expect a military commander to react to a subordinate claiming that orders from the commander-in-chief were unlawful. (Think Jack Nicholson in A Few Good Men.) The commission rejected entirely a defence request to allow expert testimony from six international law experts. And the presiding officer twice addressed one defence lawyer as "sunshine".

But the problems go deeper than the personalities. The military commissions are empowered by presidential order to prosecute persons who should not go before military commissions in the first place, including prisoners of war (who must be tried by courts martial) and persons charged with offences unrelated to any armed conflict. The rules also permit secret evidence and closed hearings to be used. And military commission decisions (unlike those of courts martial) cannot be appealed to an independent civilian court.