The international media don't send reporters to cover genocides, it seems. They cover genocide anniversaries.

We've just finished a spate of front-page stories, television docu-histories and somber panel discussions on "Why the Media Missed the Story" in Rwanda, pegged to the 10th anniversary of one of the most shocking tragedies of last century, or any century. More than 500,000 people were killed in a small African country in only 100 days, and the world turned away.

But even as the ink was drying on the latest round of mea culpas, another colossal disaster in Africa was already going uncovered.

Nearly a million people have been displaced from their homes in western Sudan; many have fled into neighboring Chad. They report that militias working with the Sudanese government have been attacking villages, ransacking and torching homes, killing and raping civilians. These armed forces are supposedly cracking down on rebel groups based in the Darfur region, but in fact they are targeting the population.

The rainy season comes to western Sudan in May. If farmers don't get back to their villages by then, the crops will not get planted this year -- and that could mean mass starvation as well. But no one will go back as long as the janjaweed (literally, "armed horsemen") militias remain in the area.

So where are the journalists?

At the annual meeting of the Overseas Press Club last week, I took a random and admittedly unscientific survey of foreign editors.

"Do you have anyone in Darfur?" I asked.

"We did have someone there!" said one editor brightly. "But she's been covering all of Africa." He changed the subject to authoritarian trends in Putin's Russia.

"We're covering the Washington angle this week," said another, referring to the Bush administration's conundrum of how to wrap up a peace agreement between the government of Sudan and rebels in the southern part of the country -- just as Khartoum is attacking another set of ethnic groups in the west.

"I think we have a stringer now in Chad," offered a third.

If few editors could find Rwanda on a map 10 years ago, fewer still have found Darfur today.

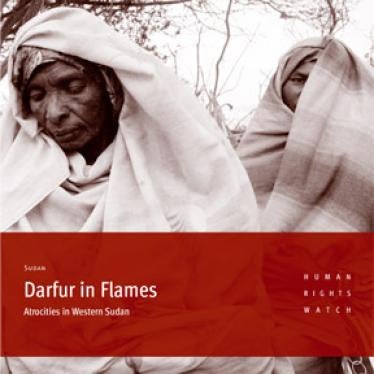

Of course, Khartoum isn't giving visas to camera-wielding international TV crews. But although Darfur is hard to get to, it isn't impossible. A Human Rights Watch researcher just spent three weeks sneaking back and forth to Sudan from Chad, and she brought back with her solid evidence of what's happening on the ground.

For Human Rights Watch to adequately cover the tragedy in Darfur, we have to take people away from their regular jobs -- following the Lord's Resistance Army in northern Uganda, the worsening civil war in Ivory Coast and other global tragedies. But if we can do it, with the scarce resources of a nonprofit, then why not the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times?

Part of the answer is Iraq. The Chicago Tribune's Cairo bureau chief, for instance, who could be covering north Africa, just got bundled off for another tour of Baghdad. The war is a story that involves Americans -- our men and women in uniform -- and Americans are understandably preoccupied with it. (Ten years ago, the media were transfixed by the O.J. Simpson trial -- so maybe you can call this progress.) Covering the war in Iraq has depleted foreign news budgets, and sending reporters into Sudan is not cheap either.

Reporters have begun trickling to the scene. The Los Angeles Times has a correspondent en route to Darfur, as does the New York Times. But the fact is, with or without a war in Iraq, American journalists are generally slower to cover mass death if the victims are not white. The Rwandan genocide is a case in point.

The tragedy in Darfur may not cross the genocide threshold, but should that really make a difference? Thousands of civilians have been killed, and the pattern and intent behind these massive crimes must be carefully mapped and loudly broadcast around the world if there is to be any hope of stopping them.

We need more information and more firsthand reporting. We need reporters at the scene, making this disaster real to their audience by telling the stories of individual victims.

It's the media's job to inform us. They should do it, and quickly -- because 10 years from now there won't be any excuse for another round of hand-wringing.