This year's State Department Human Rights Country Reports are largely honest and hard-hitting, Human Rights Watch said today, while urging the Bush Administration to heed the reports' findings in setting policy towards key allies.

For the most part, the reports candidly describe human rights abuses committed by U.S. allies in the war on terrorism, including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Uzbekistan, China and Russia. One exception is a reference in the reports' introduction to elections in Pakistan producing a "reasonably representative" government. In fact, key moderate parties were banned from standing in the elections for parliament last year.

"The Bush administration has not pulled many punches in this report," said Tom Malinowski, Washington advocacy director for Human Rights Watch. "But it should also be troubled that some of its closest allies in the war on terrorism engage in repressive practices that fuel support for terrorists."

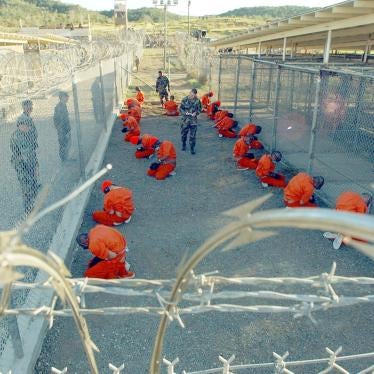

Human Rights Watch pointed out that the State Department reports condemn practices abroad in which the United States itself reportedly engages. For example, the reports condemn as torture so called "stress and duress" interrogation techniques such as sleep deprivation and the shackling of prisoners in painful positions in a number of countries, including Burma, Iran, Egypt, and Eritrea. According to U.S. officials quoted in press accounts, U.S. interrogators have used similar techniques against suspected Al Qaeda detainees in Afghanistan and elsewhere.

The United States has also reportedly transferred custody of terrorist suspects to countries that the State Department reports condemn for torturing prisoners.

"The Bush administration needs to address this glaring inconsistency," Malinowski said. "Its moral clarity will mean little if it doesn't rebuild its moral authority."

Comments on specific country chapters of the State Department reports follow:

Afghanistan: The report rightly calls attention to violent assaults on nongovernmental and humanitarian organizations, the lack of progress towards accountability for past abuses, continued attacks on ethnic Pashtuns, and the reappearance of the religious police who enforce restrictions on public conduct and dress. Nevertheless, the report overstates human rights progress since the fall of the Taliban. For example, the authority and effectiveness of the Karzai government is exaggerated, and human rights abuses leading up to last year's Loya Jirga meeting are downplayed. References to "regional commanders" or "rogue warlords" are carefully couched in language that doesn't convey their dominant role in the country. Grave abuses against Afghan women, in the western province of Herat and elsewhere, are mentioned, but these reports are usually attributed to other sources in a way that leaves unclear whether the U.S. government believes them. In Geneva, at the UN Commission on Human Rights, a draft resolution on Afghanistan is under consideration, but the US is strongly opposing any reference to a UN recommendation for a mechanism to catalogue abuses committed by all parties since 1978.

China: The report candidly describes China's overall human rights record. Commendably, it criticizes China for misusing the war on terrorism to justify a crackdown against Uighur separatists and peaceful religious leaders. It is more detailed and critical than past reports on China's restrictions on the Internet, and is more skeptical than past reports about China's progress on legal reform. It includes a strong section on abuses of religious freedom, and good analysis of economic dislocation and protests by unemployed workers. At the same time, the report gives credit to China for issuing invitations, without conditions, to U.N. human rights experts, even though no such visits have yet been scheduled. It does not adequately address the lack of freedom of association and expression for AIDS activists and journalists reporting on the epidemic. And it overplays progress in Tibet, crediting China for early releases of dissidents, although many had served all but a few months of their terms - and none should have been sentenced in the first place. Moreover, on the basis of this overwhelmingly damning report, the United States should have introduced weeks ago a resolution on China at the U.N. Human Rights Commission and launched a diplomatic campaign to promote it.

Colombia: The State Department must by law certify twice each year whether Colombia is cutting ties to paramilitary groups to maintain full funding for military aid to the country. This year's report acknowledges that members of Colombia's armed forces and police continued to commit serious human rights abuses, in particular through continuing links to illegal paramilitary groups. However, throughout the report and despite abundant evidence of these links, this alliance is minimized by language that reduces the phenomenon to isolated units and individual officers. The report also overplays a decline in massacres attributed to paramilitary groups. In fact, this decline is a result of a tactical decision by the paramilitary leadership, currently engaged in negotiations with the government, and not of effective measures by the government to arrest and prosecute paramilitary leaders. Finally, the report makes an unfortunate attempt to defend the work of Colombia's Attorney General, who has systematically undermined and derailed many of the key human rights cases mentioned in the report.

Kazakhstan: By law the State Department must certify that Kazakhstan is making progress on human rights to continue assistance to its government. This year's report accurately concludes that the Kazakhstan government's already poor human rights record "worsened" in 2002.

Nigeria: The report discusses abuses committed by police, army and security forces as well as vigilante groups including the Bakassi Boys in Abia and Anambra states and the O'odua People's Congress (OPC) in the southwest. It also notes human rights abuses by the police against the OPC and other groups. Armed groups were also used by politicians and their supporters to carry out violence and intimidation against political opponents, and the report correctly states that serious violence occurred during the local primaries of the ruling People's Democratic Party (PDP). It notes that a commission of inquiry was set up to investigate clashes in Benue and neighboring states, including the killing of over two hundred civilians by the military in Benue State in October 2001. However, it fails to stress that no action has been taken against the members of the Nigerian armed forces who took part in these killings. The U.S. Congress has since suspended Nigerian participation in U.S. military training programs under International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) until the Bush administration submits a report to Congress about whether members of the armed forces responsible for taking part in the massacres in Benue are being suspended from service and what steps are being taken to bring them to justice.

Pakistan: In general, the report paints a sobering picture of the way the Musharraf government hijacked democracy and boosted the military's power through a referendum, rigged elections, and constitutional amendments. It highlights an increase of sectarian attacks on Christians, continuing abuses suffered by women, government controls of the media, and wide-scale detentions of political opponents and activists. However, the introduction of the report inexplicably claims that the government elected in what it concedes were rigged elections was "reasonably representative." The report is also weak in its description of Pakistan's Anti Terrorist Act, amended in 2001 and strengthened last November by Musharraf, and of the country's anti-terrorist courts. This highlights how U.S. policy towards Pakistan has increasingly become driven by cooperation in the war against terrorism, which has muted U.S. efforts to promote democratic change and basic human rights.

Uzbekistan: The State Department by law must certify that Uzbekistan is making progress on human rights to continue assistance to its government. The report offers scant evidence of progress. It paints a straightforward picture of the arrest and brutal treatment of human rights defenders in Uzbekistan, and the virtually complete absence of political and media freedoms. It acknowledges that more than 6,000 people remain in prison in the country for political and religious reasons and that prisoners are routinely subject to torture. And it describes how prosecutors in Uzbekistan's courtrooms are able to dictate proceedings and, almost always, obtain guilty verdicts. At the same time, the report consistently refers to non-violent religious prisoners, the victims of a merciless campaign of religious persecution, as "suspected Islamic extremists" or people suspected of having "extremist Islamic political sympathies," terms that the Uzbek government could read as justifying its policy of arresting and torturing members of unregistered religious groups. The report also incorrectly claims that the Uzbek government "permitted the existence of opposition political parties." In fact, no genuine opposition party is permitted to function. Discussion of Uzbekistan's highly restrictive religion law focused disproportionately on how it affected small Christian groups.