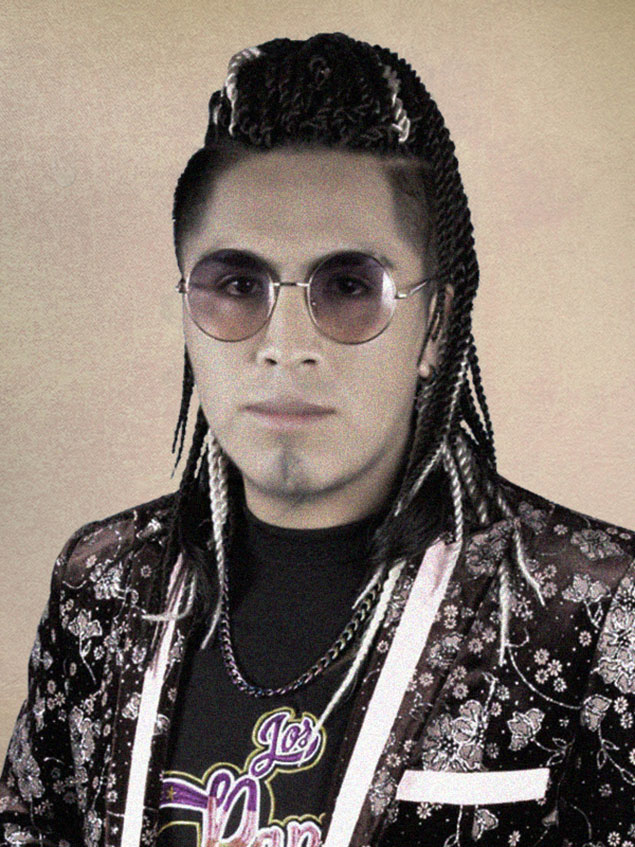

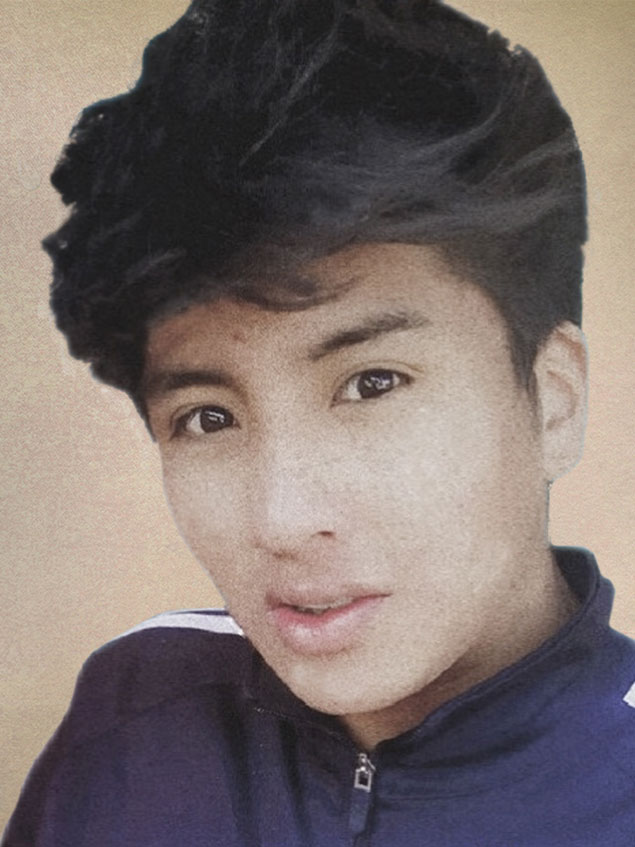

Marco Antonio Samillán was painting his family’s small store in Juliaca, a city in Puno department in southern Peru, when he learned police had killed a protester near the city’s main airport.1

Protests had broken out across the country in the wake of then-President Pedro Castillo’s attempted coup on December 7, 2022.2 In Juliaca, too, demonstrators took to the streets in largely peaceful protests, as anxiety over the national political crisis melded with local concerns ranging from poverty to access to public services.3

Samillán, 30, a medical student, ran up to the first floor of the home he shared with his seven siblings and grabbed his medical kit. He headed to the airport – knowing that if one protester had been killed, there might soon be other victims in need of urgent medical attention.4

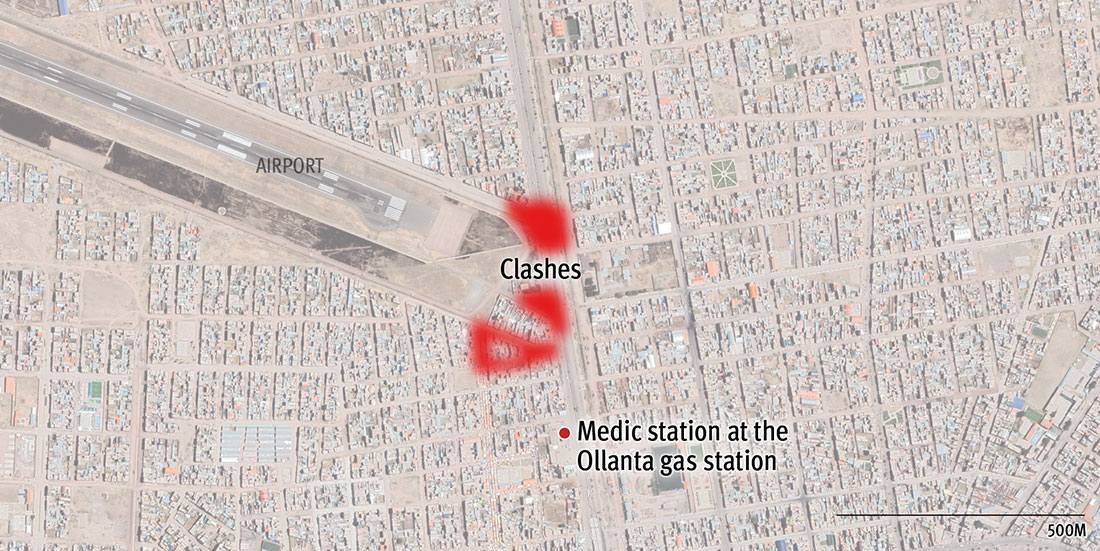

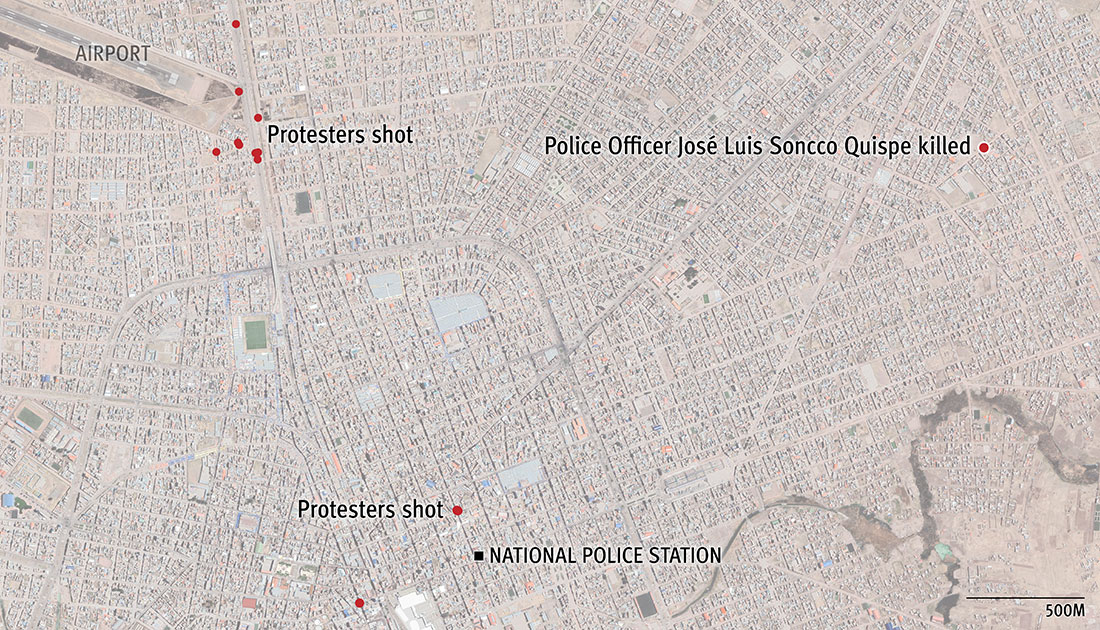

By the time Marco arrived at the airport, clashes between police and protesters were reaching a boiling point. The people at the front lines of the protest, closest to the airport, threw rocks toward police officers. But those further back from the airport, who constituted the majority of the protesters, appeared largely peaceful. Police pelted protesters with tear gas, and later used lethal force to fire into the largely peaceful crowds. The first victim was a bystander — 19-year-old Reynaldo Illaquita Cruz — who was shot in the thorax as he walked past demonstrators on his way to lunch.5 By the end of the day, 17 other protesters — including three children — were shot and died. One police officer also died later that day approximately three kilometers away from the airport. 6

Marco, according to his sister, was attending the wounded with other volunteer medics. At one point in the protest, Marco was forced to move away as police advanced, and he went to a surrounding neighborhood about a block from the airport, where he had been told there were several wounded people.7

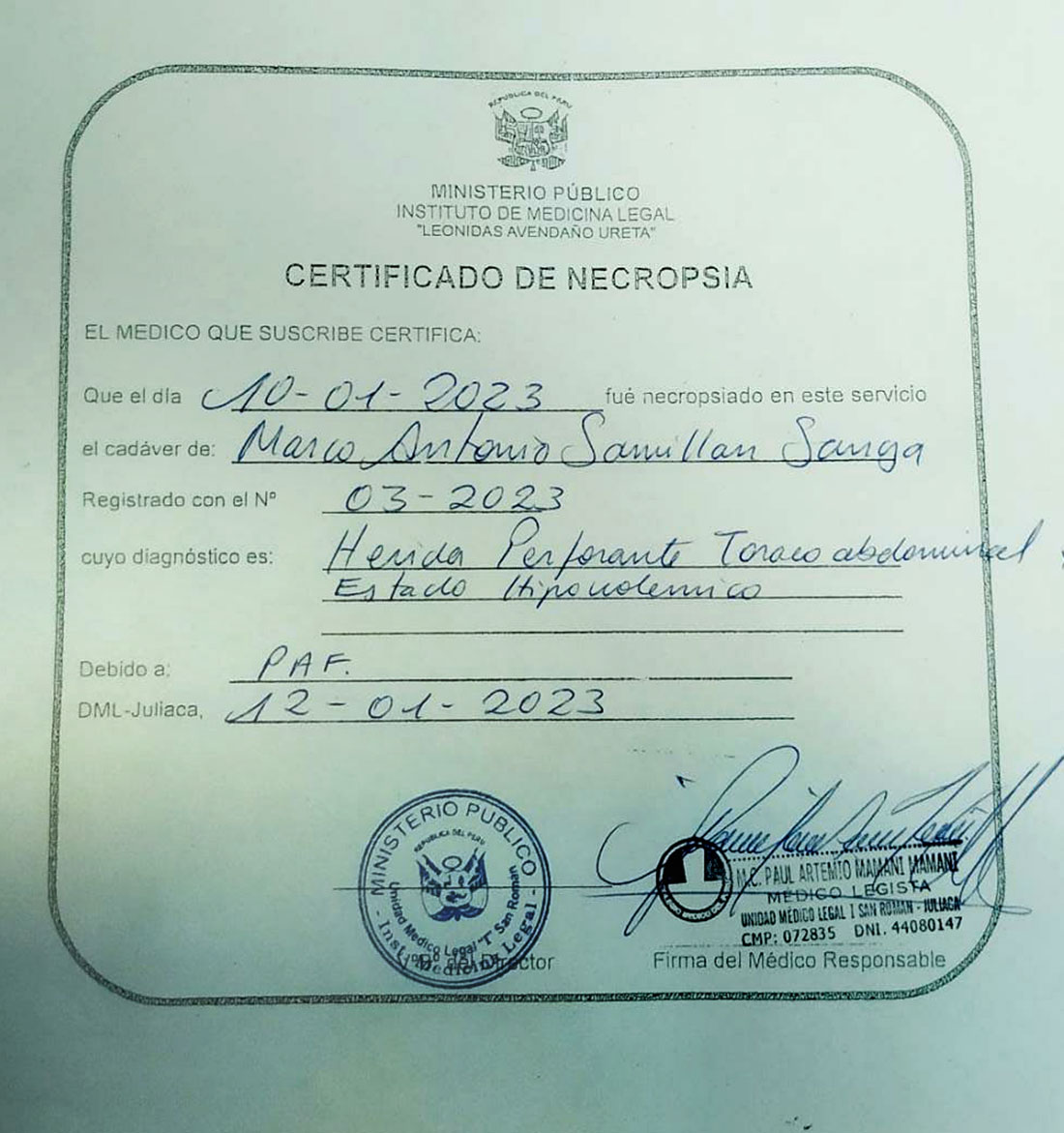

As he bent over to help a wounded man lying in the street, Marco was shot in the back. A witness rushed out, and with the help of another person dragged Marco to a nearby house. He was taken by ambulance to a nearby hospital.8

“My brother arrived at the hospital alive,” said his sister Milagros Samillán. “Some of his fellow medical interns were attending there. They prioritized him… They took him to surgery and tried to stop the internal bleeding, but he went into cardiac arrest and died.”9

In late January, President Dina Boluarte said that “Puno is not Peru,” and claimed that the “majority” of those who died in Juliaca were killed by homemade weapons. The evidence establishes this was incorrect. More than three months later, no one has been held to account for the lethal force used against Marco and the others killed that day. The Attorney General’s Office has opened investigations, including into the responsibility of Boluarte and the then Ministers of Defense and the Interior, under whose command the military and police were at the time of the events, but in Juliaca and nationwide, there are serious concerns about how these cases are being handled. The Ministers of Defense and the Interior remain in post.

Meanwhile, Milagros, and the other families of victims, wait. “We want those who committed these acts to face justice,” she says.10

What follows is an account of the January 9 protests in Juliaca and the final moments of Samillán and other victims. To piece together the events of that day Human Rights Watch reviewed more than ten hours of video footage posted to social media and 543 photographs from the protests in Juliaca. We also interviewed 26 witnesses, lawyers, prosecutors, and family members of victims, and reviewed autopsy reports and the criminal file of the investigation by the local prosecutor’s office.

Our conclusion: Peruvian security forces used indiscriminate and excessive force against protesters, in violation of international laws. Nearly all victims died of gunshot wounds caused by assault rifles and handguns. A credible, impartial judicial investigation is now needed, going up the chain of command, to ensure that those responsible are held to account.

A Country in Chaos

On December 7, 2022, Peru’s then-President Pedro Castillo announced measures amounting to a coup, including the temporary dissolution of Congress and the “reorganization” of the judiciary.11 Democratic institutions and civil society quickly rejected Castillo’s actions. Congress approved Castillo’s removal the same day. Police detained him and prosecutors charged him with rebellion, conspiracy, and abuse of power.12 Vice President Dina Boluarte assumed the presidency and announced that she would govern until the end of Castillo’s term in 2026.13

Thousands of people took to the streets across the country with a variety of demands, including a call for early elections.14 These protests in part reflected popular disenchantment with the current political system, seen by many as corrupt, and driven by private interests. In the face of the protests, Boluarte changed her initial position and called on Congress to approve early presidential and legislative elections.15 Congress has rejected this call five times.16

In Juliaca, protesters first took to the streets around January 4 to draw attention to the city’s high levels of poverty and lack of access to public services. They also demanded an end to police repression.17 Protesters soon blocked the department’s main highways and attempted to take the airport – leading it to suspend operations on January 6.18

Although some protesters in Juliaca and elsewhere committed acts of violence during demonstrations, the reaction of the police and military was brutal. In total, 49 protesters and bystanders were killed from December through February 2023, mostly in southern Peru, as police and military repeatedly used indiscriminate and excessive force against protesters.

The Morning of January 9 in Juliaca: Protesters March Peacefully to the Main Airport

On the morning of January 9, the atmosphere in Juliaca was jovial as protesters gathered mostly in the north of the city. At around 9:30 a.m., hundreds crossed the Wonders of Juliaca bridge and headed south toward the city center.19 The 60-minute march took them — chanting, singing, and laughing — to the east end of Juliaca‘s Inca Manco Cápac International Airport. There they met another group that had already gathered in front of the fences around the tarmac.20

At 10:34 a.m., roughly 75 police officers stood along the east end of the airport behind fences that were knocked down during protests earlier that month.21

A large group of protesters continued marching past these officers into the city, gathering first at the Plaza de Armas, and arriving at the Superior Court of Justice of Puno at 11:40 a.m. But around a thousand others remained on Avenida Independencia, just outside of the airport.22

Peru police regulations prohibit shooting tear gas canisters “at people’s bodies.” The regulations warn of “lethal risk and serious harm” from the use of tear gas.23 The chief of the Lima police region said officers should fire tear gas canisters at the sky or the ground, never horizontally at people.24

In Juliaca, police first used tear gas on the crowd on Avenida Independencia at 11:38 a.m., according to reports by Radio Exa Asillo, a local radio station. A gap then opened between the protesters and police at the edge of the airport, but the protesters largely stayed where they were. Police did not fire additional tear gas for the next seven minutes.

As protesters continued to file past the airport, a 6x6 and two 4x4 covered trucks, as well as several pickup trucks, transported roughly 50 military officers to the east end of the tarmac. They lined up in formation 80 meters west of the police stationed closest to the airport’s eastern fence.

Security Forces Converge at Airport, Standoff Soon Turns Violent

Using videos and photographs shared online, Human Rights Watch identified the number and location of police and military officers on the Inca Manco Cápac tarmac at around 12:20 p.m. on January 9, 2023. © 2023 Diario Sin Fronteras

By 12:20 p.m., over 450 officers were stationed at the Inca Manco Cápac airport, as can be seen in videos recorded on the tarmac and shared on Facebook.25 In addition to the around 50 military officers, the group was mostly made up of police from Juliaca, Lima’s Special Operations Team, and the National Police Special Services Units from Lima, according to a lawyer representing the victims and a criminal file seen by Human Rights Watch.26

At 12:20 p.m., the commanding general of the military’s Fourth Mountain Brigade of Puno, Manuel Fernando Alarcón Elera, told a reporter inside the airport that the majority of protesters were acting in a peaceful manner, but that “three, four, five” of them were behaving violently to provoke the police and that “the police have tear gas that they will use at the appropriate moment.”27 Alarcón Elera was accompanied by General David Pablo Villanueva, head of the national police in Puno department at the time. Villanueva was removed from his position on March 18, 2023.28

Eight minutes later, the officers began firing tear gas as some of the protesters tried to enter the airport.

Over the next four hours, some protesters tried to enter Juliaca’s airport, threw rocks with huaracas (a type of sling), and fired homemade fireworks (avellanas) at the security forces. The security forces responded by opening fire in the direction of the protesters and bystanders.29

Three Facebook livestreams recorded from the northeastern corner of the airport show a rapid rise in the level of force used against protesters over 20 minutes from 12:45 p.m., from infrequent warning shots to an increased use of tear gas and frequent gunfire.

The violence continued to escalate over the next hour.

At 1:41 p.m., a Peruvian military Mi-171Sh cargo helicopter seen earlier that day outside the Inca Manco Cápac terminal began circling above the protesters near the airport.30

Soon after, an officer in the helicopter began firing what appears to be tear gas at the protesters below.

Witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch confirmed that the

police who stood along the east end of the airport shot firearms in

the direction of unarmed protesters. Out of the 474 photographs and

49 videos that Human Rights Watch verified near the Juliaca airport,

not one showed protesters carrying firearms. Peru’s chief of police

told Human Rights Watch that they did not seize any firearms from

protesters in Juliaca, or in protests elsewhere in the country.31

However, protesters did set off homemade fireworks in the direction of officers stationed at the eastern end of the airport and at the helicopter as it flew overhead.

Volunteer Medics Mobilize to Treat the Wounded; Many Do Not Survive

Protesters were wounded soon after the clashes began. Other protesters brought the wounded to the Ollanta gas station, where volunteers gave them first aid. Serious cases were transferred to medical centers and the Carlos Jorge Medrano hospital.32 Milagros Samillán said that her brother, Marco, and several health brigade members, attended the wounded.33

Killings Begin

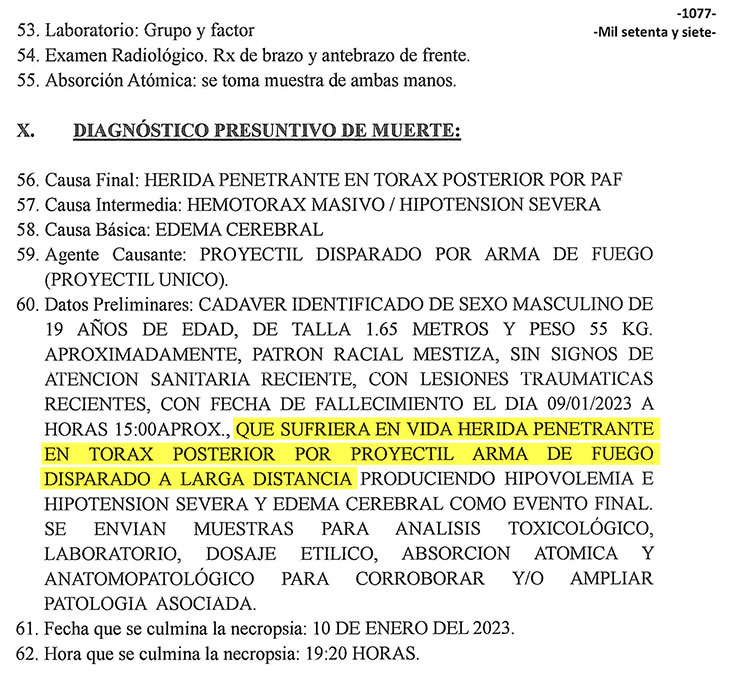

Using a combination of testimonies, videos, photos, autopsies, and the criminal file, Human Rights Watch confirmed that 15 of the 18 civilian victims died from wounds caused by gunfire. In at least 8 of these cases, evidence suggests that security forces fired directly at the victims’ vital organs, such as the head and lungs. Three other victims died from pellets fired by shotguns used by police.

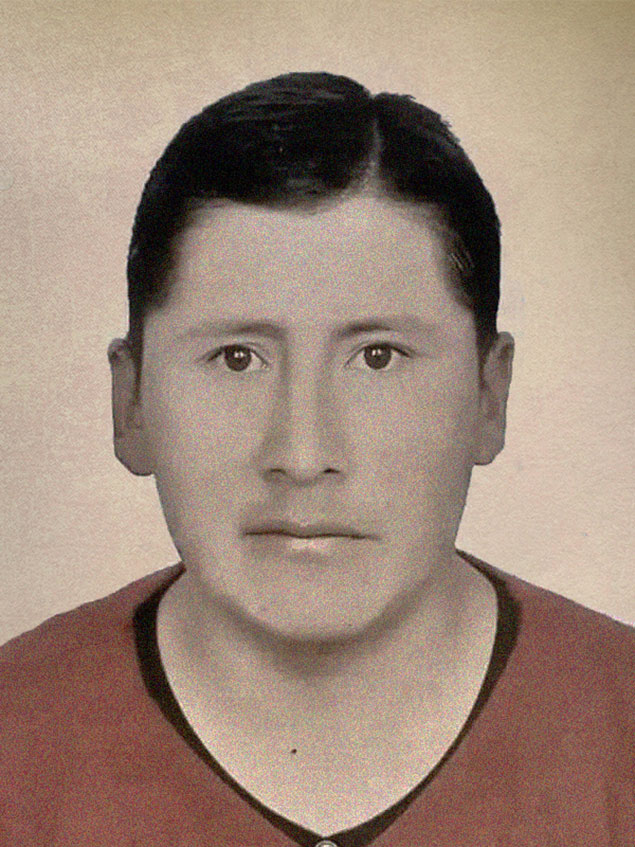

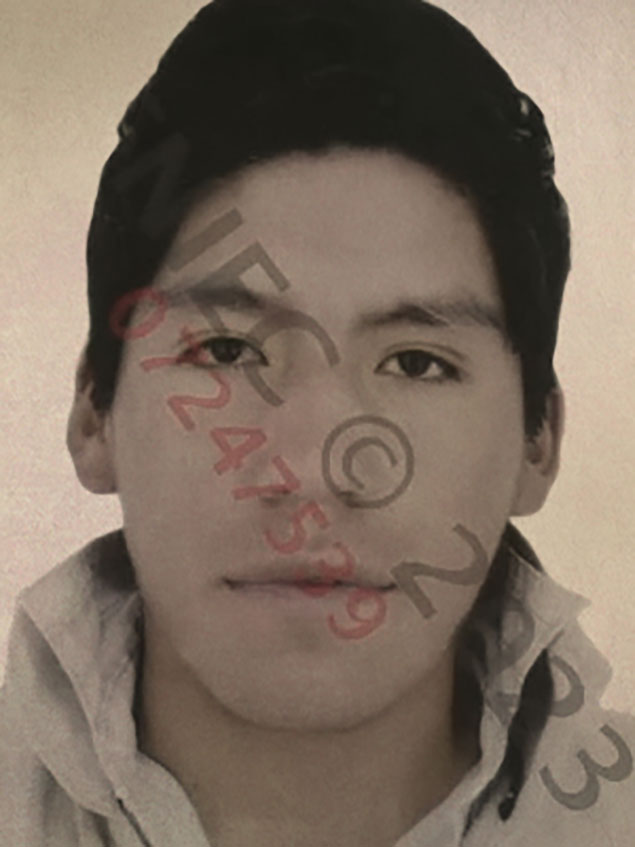

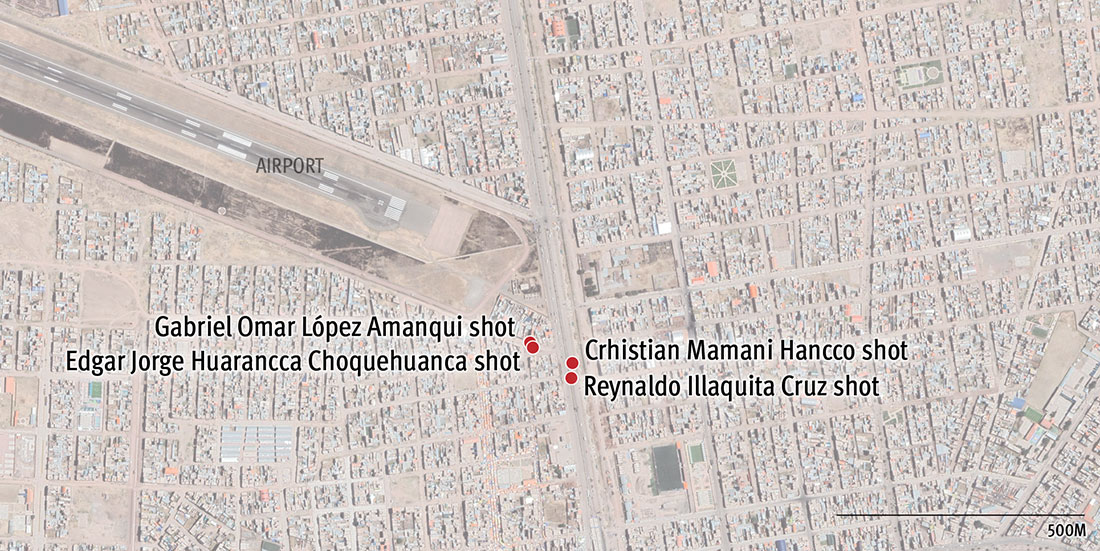

The first victim was a bystander, 19-year-old Reynaldo Illaquita Cruz. He worked at a sawmill to save money for the business management degree he hoped to earn, but for which his family could not afford to pay. At around 1:30 p.m., he left work on Avenida Independencia to go for lunch, when he was shot in the thorax with a 7.62mm bullet as he was walking past the demonstrators.34

A photo of Reynaldo Illaquita Cruz, as well as his autopsy report which states a “long-range firearm” caused his fatal wound. © 2022 Courtesy of Reynaldo Illaquita Cruz’s family. The highlighted text indicates that he “suffered from an antemortem penetrating wound in the rear thorax due to a long-distance firearm projectile.”

The size of the bullet that killed Illaquita Cruz matches the size of ammunition used in Kalashnikov-pattern assault rifles. Both military and police officers carried this weapon at the airport earlier that day.

7.62x39mm cartridges for Kalashnikov-pattern rifles and marked with a PNP headstamp, standing for Peruvian National Police, were found near the airport later that day.35

Forty minutes later, 35-year-old Gabriel Omar López Amanqui, a construction worker and father of two children, was on his way to his father’s house.

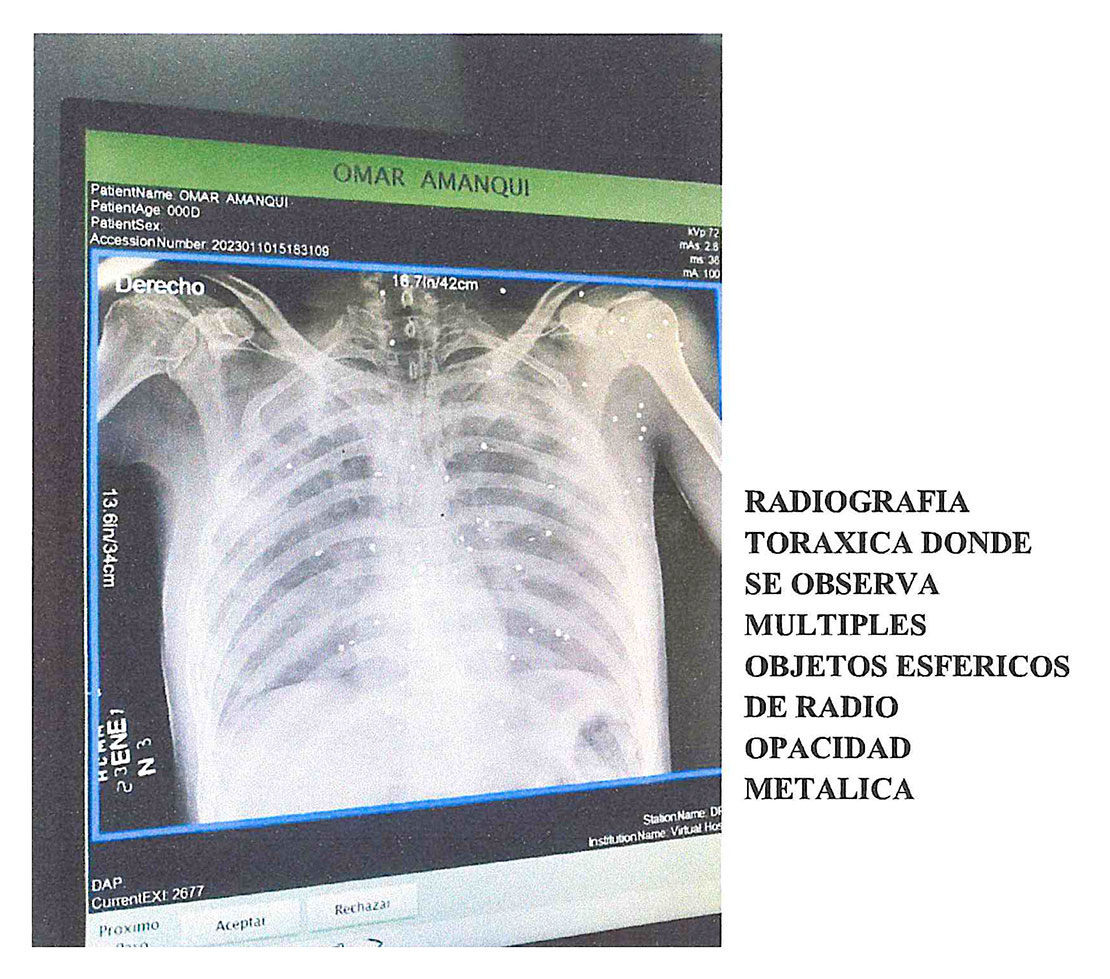

He was shot with a lead pellet shotgun just west of the same avenue.36 Photos taken at 2:08 p.m., show protesters carrying López Amanqui away from a group of at least 21 police officers who were stationed at the southeast edge of the airport at that time. Additional videos and photos from 130 meters south of the southeast corner of the airport show protesters and volunteer medics treating the many small wounds to López Amanqui’s back before loading him onto a motorcycle.37 In these images López Amanqui is seen being evacuated on a motorcycle.38 The driver took López Amanqui to Posta Revolución Medical Center. His relatives rushed there too. Later that day a doctor told them that López Amanqui had died from gunshot wounds. Lead shotgun pellets had left 72 holes in his body, according to his autopsy and the ballistics analysis.39

An X-ray included in Gabriel Omar López Amanqui’s autopsy report shows many pellets lodged in his thorax.

The autopsy report states: “Thoracic X-ray showing multiple spherical objects with metallic radiopacity.”

Autopsy report on file at Human Rights Watch.

At 2:16 p.m., roughly eight minutes after López Amanqui was shot, two other men were receiving treatment at the makeshift medical station just south of where López Amanqui was shot. One had at least 25 similar small wounds in his right arm. Next to him, another man was bleeding from his forehead.40

Pellets, fired from 12-gauge shotguns, likely caused the wounds sustained by both López Amanqui and the man receiving treatment for wounds to his arm. Videos and photographs show police officers using shotguns throughout the day, and protesters collected and shared images on social media of expended shotgun pellet cartridges. The Peruvian police’s internal manual of regulations for less lethal weapons mentions shotguns firing pellets but does not provide guidelines on how to use them or specify what type of ammunition or size of pellets are allowed.41 The chief of the Lima police region said they should aim shotgun pellets at the lower body.

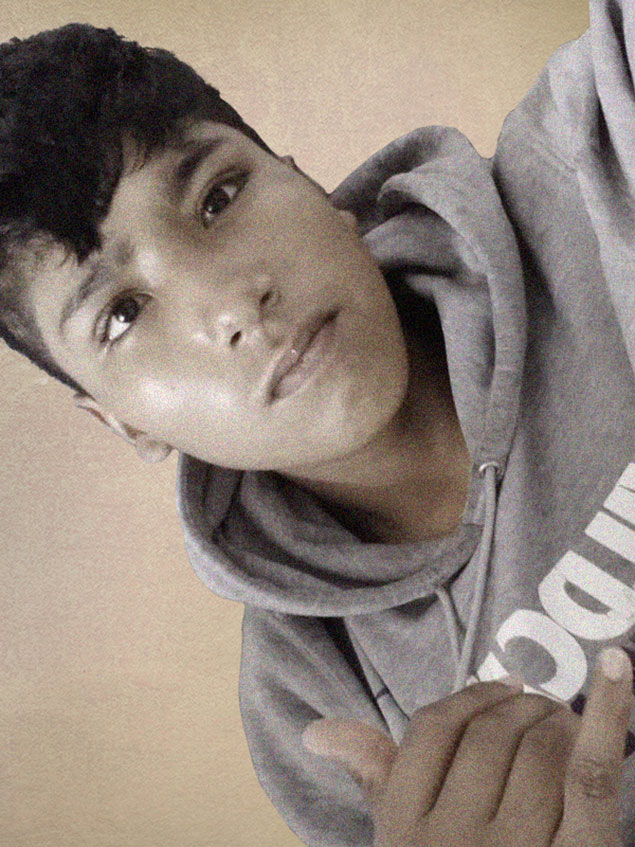

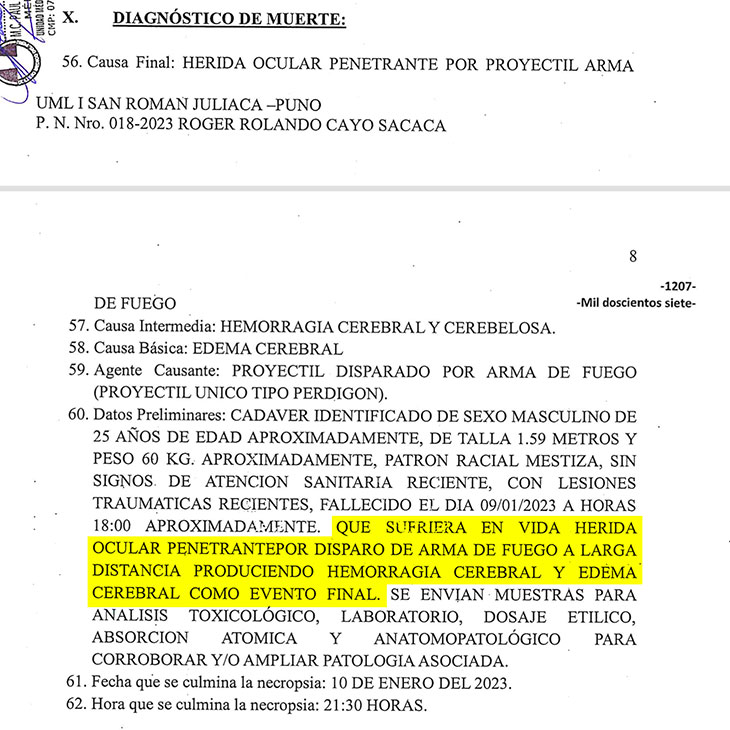

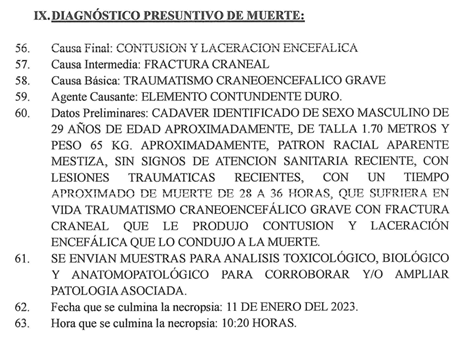

At around 2:30 p.m., a projectile with the “oval metallic density” of a pellet hit Roger Rolando Cayo Sacaca, a 25-year-old motorcycle taxi driver, in his eye. His autopsy report states a long-range firearm shot the projectile into his brain, causing the cerebral bleeding and cerebral edema that killed him. He had come to see the protests in Juliaca’s main square, Plaza de Armas, with a friend, and was walking home along the Avenida Independencia. Cayo Sacaca, who wanted to become a mechanic, was finishing high school, and working as a motorcycle taxi driver to help his parents.42

A photo of Roger Rolando Cayo Sacaca, as well as his autopsy report which states that a single shot-type projectile from a long-range firearm caused his fatal wound. The highlighted text indicates that he “suffered from an antemortem penetrating eye wound by a long-distance firearm shot producing cerebral hemorrhage and cerebral edema as the final event.” Autopsy report on file at Human Rights Watch. © 2022 Courtesy of Roger Rolando Cayo Sacaca’s family

Edgar Jorge Huarancca Choquehuanca, a 22-year-old gastronomy student, was shot in the head and chest with 9mm caliber bullets just before 2:56 p.m. 43 Protesters rushed him away from the airport on Jirón Andahuaylas to the Ollanta gas station where volunteers had set up a makeshift medical center.44

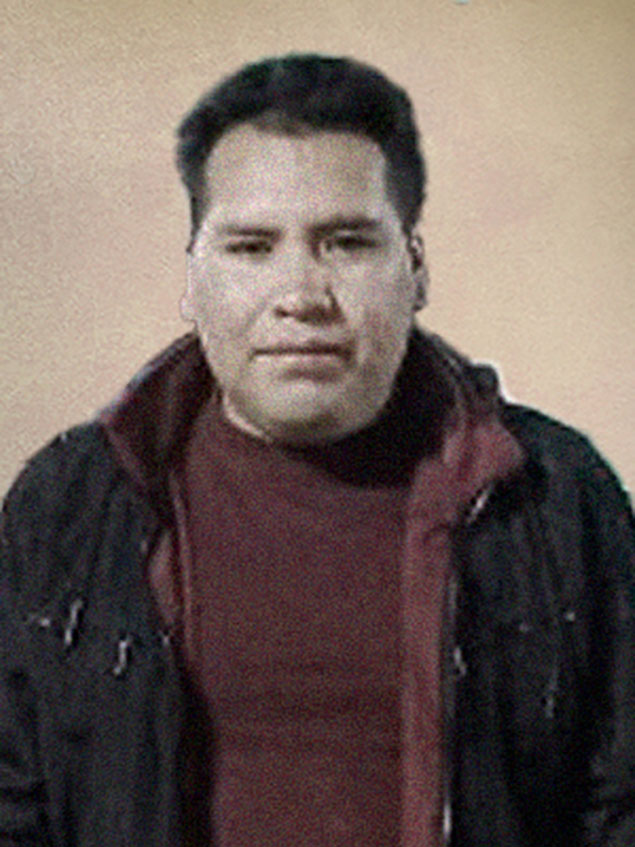

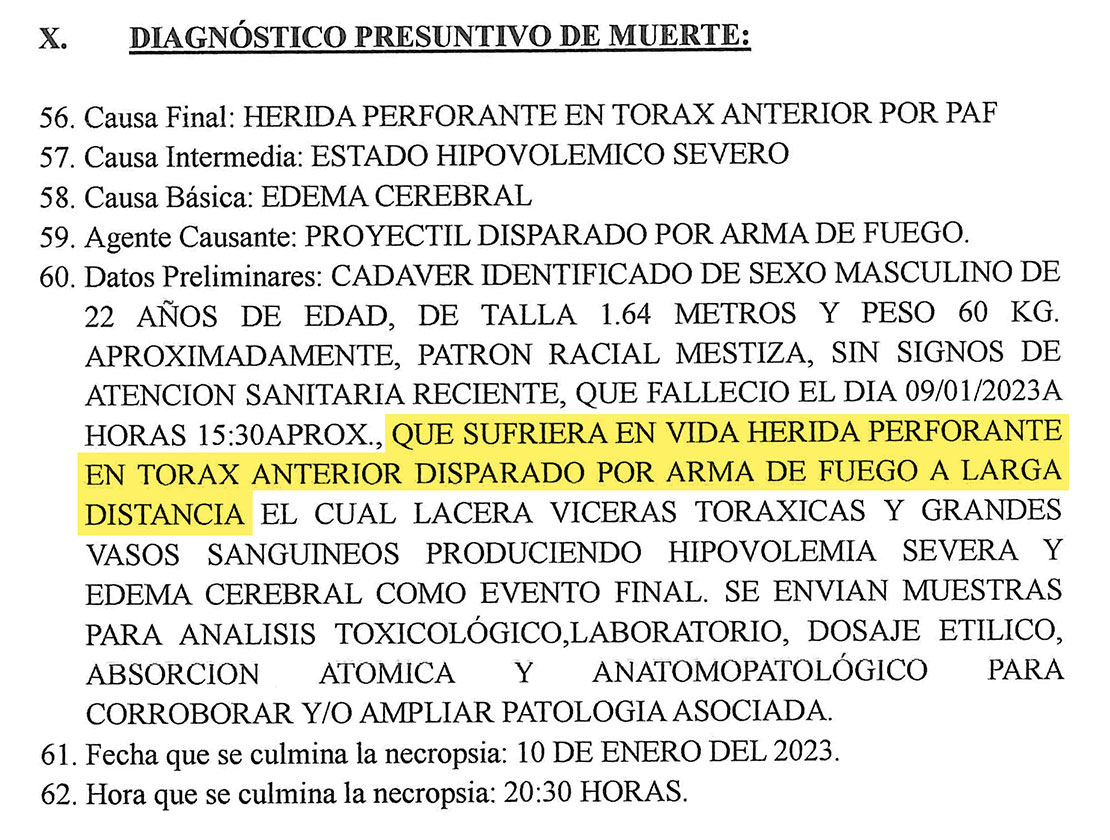

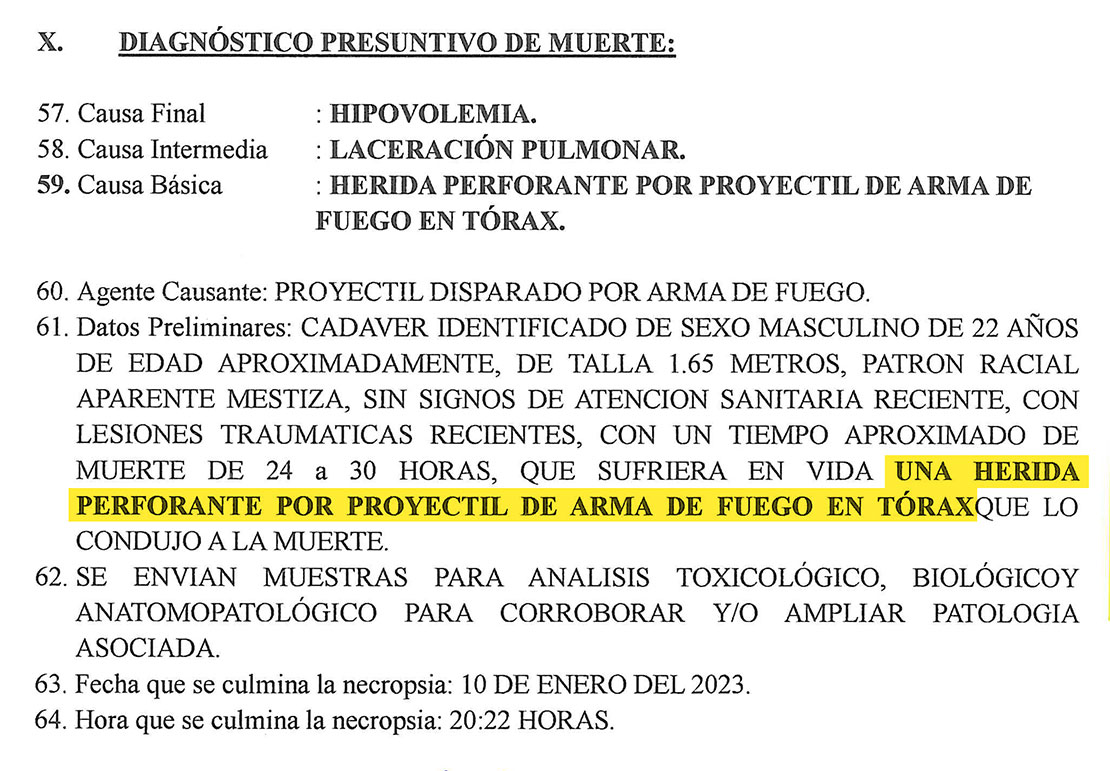

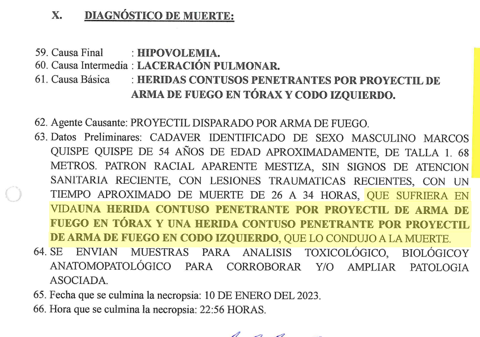

Around 3:30 p.m., Crhistian Mamani Hancco, a 22-year-old singer and dancer, was shot in the thorax and through both lungs as he returned home with a friend along the Avenida Independencia where police officers were shooting at protesters according to a witness.45 He died of these wounds. His autopsy report declared that they were caused by a “long-range firearm.”46

Crhistian Mamani Hancco, dancer who was killed during the January 9, 2023, protests in Juliaca. © 2022 Courtesy of Crhistian Mamani’s family

The Killing of Samillán, the Volunteer Medic

Milagros Samillán recounted to Human Rights Watch what she heard from Marco’s health brigade colleagues:

At around 4 p.m., the police were attacking demonstrators with more force, firing tear gas and firearms, so several of the demonstrators and the health brigade members ran out along the main avenue, Avenida Independencia. According to what one of them told me, my brother ran alone, in the opposite direction, into the neighborhood, because he was told that there were several wounded people lying on the ground about a block from the airport, on the Avenida Abancay, between Ugarte and 24 de Junio streets.47

Ten minutes later, Marco Antonio Samillán was shot in the back while providing first aid to an injured young man. His sister recounted what happened next:

A lady told me that she saw from her house that my brother bent down to the ground and began to try to revive another young man who was wounded on the ground. [Marco] was helping him and had his back to the street when he was hit by a bullet. She said she only saw Marco fall to the ground, but not who shot him. She told me that there were a lot of police in that street and there was no way to record [what was happening] because the police were firing tear gas canisters into people’s houses.48

[She] left the house where she was, and together with another person dragged Marco to another nearby house. She saw my brother was getting paler, and that is when they realized that he might be bleeding internally. She asked the people in the house for a blanket and with the help of two other people they put Marco on the blanket and took him to a nearby medical center. From there an ambulance took him to the Carlos Monge Medrano hospital.49

My brother arrived at the hospital alive, according to what the nurse told me. Some of his fellow medical interns were attending there. They prioritized him... They took him to surgery and tried to stop the internal bleeding, but he went into cardiac arrest and died.50

Crackdown on Protesters Continues through the Evening

Protesters calling for help for Nelson Huber Pilco inside the airport after officers shot him. © 2023 AFPTV via Getty Images

The killings near the airport continued. Nelson Huber Pilco, 22, from the San Miguel district, was shot in his thorax with live ammunition 12 meters inside the airport’s eastern fence at around 4 p.m. He died of his wounds.

Pilco worked as a motorcycle taxi driver to help support his parents and five siblings.51

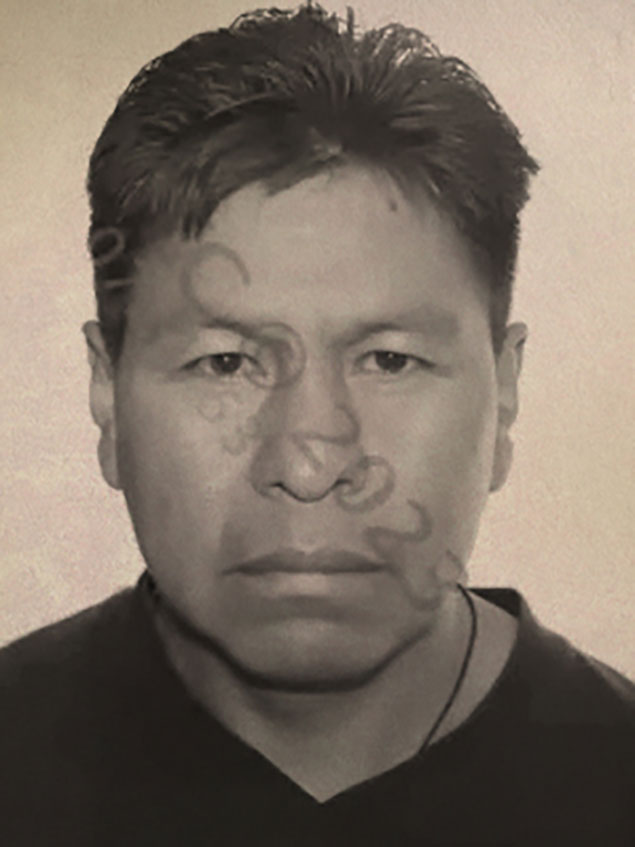

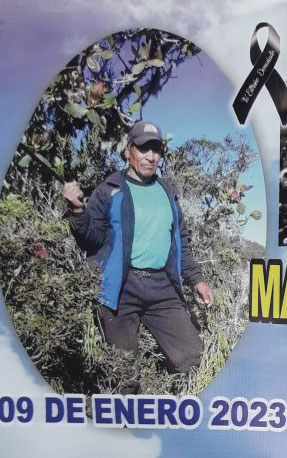

A memorial photo of Marcos Quispe Quispe. © 2022 Courtesy of Marcos Quispe Quispe’s family

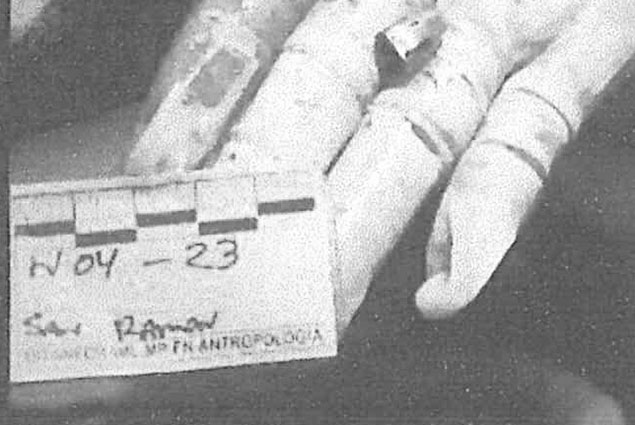

Marcos Quispe Quispe, 54, was a bricklayer who took care of his daughter and his two-year-old granddaughter. At 4:30 p.m., he was shot twice while he watched the protests at Avenida Independencia; once in his thorax with a lead pellet gunshot and once in his left elbow.52 Quispe died from these wounds. His daughter is bereft and says she does not know how she will survive and raise her child as a single mother with no income.53

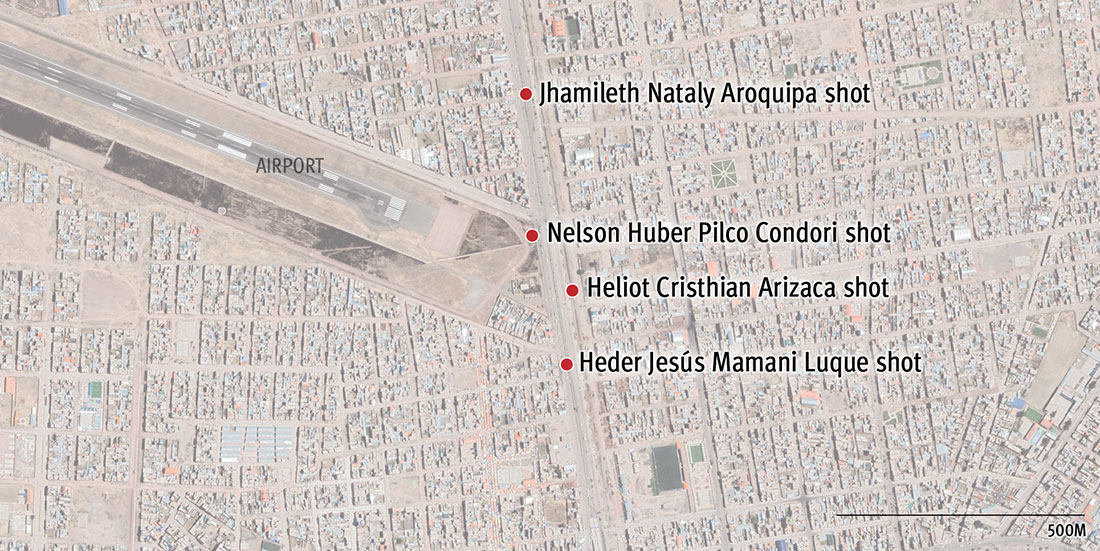

At around the same time, 17-year-old psychology student Jhamileth Nataly Aroquipa was out grocery shopping with her family at Avenida Independencia when she was shot in the stomach.54 A relative who witnessed the events told Human Rights Watch that, at the time, the police were firing tear gas canisters and firearms towards the protesters.55 The forensic ballistics expert report, reviewed by Human Rights Watch, shows that the projectile found in Aroquipa’s autopsy corresponds to a projectile for a 9mm pistol cartridge.56

[W]e were near the Grifo Pecsa gas station and considering crossing the Avenida Independencia to walk along another block and to avoid the protesters. At the time, there were clashes between them and the police – we could see the protesters were throwing rocks and the police were firing tear gas and shooting firearms. I know because I heard sounds like pistol shots. It was when we started crossing the main road that Jhamileth was shot in her stomach.57

9mm bullets are used by a variety of handguns, one of which is the Sig Sauer SP2022 handgun, which is standard issue among Peruvian National Police.58 It has an effective range of 50 meters, meaning the officer that would have shot Jhamileth was likely less than 50 meters away from the 17-year-old girl when he shot her.

Around 4:30 p.m., Heder Jesús Mamani Luque, a 37-year-old father of three, was shot in the head and died when he was walking along the same avenue, 150 meters south of the airport, according to a witness.59

Just before 5:45 p.m., 18-year-old Heliot Cristhian Arizaca was on his way home along Avenida Independencia after grocery shopping with his family when he was shot 50 meters east of the airport. He died of a long-range gunshot wound to the thorax, according to his autopsy report.60 He had planned to join the army.

Violence Spreads from the Airport to the City

Clashes between police and protesters continued into the evening of January 9, and spread to other areas of Juliaca as the night progressed.

Just before 8 p.m., three people were shot on the corner of Ramon Castilla and Jirón Moquegua, about two kilometers south of the airport and two blocks north of a Peruvian National Police station. Around the same time, another man was shot on the corner of Jirón San Roman and Simón Bolívar streets, roughly 530 meters west of the police station. All four died of their wounds.

Two videos recorded around 7:30 p.m., show a man, whom IDL-Reporteros identified as 38-year-old Héctor Quilla Mamani, get shot to the ground.61 Quilla Mamani’s autopsy report indicates he was shot in the thorax.62

Brayan Apaza Jumpiri, a 15-year-old high school student who helped his mother work in the fields, was shot in the head around 7:50 p.m. Apaza Jumpiri died on January 12, after three days in intensive care with brain trauma.63

Paul Franklin Mamani Apaza, a 20-year-old construction worker, was shot in his thorax around the same time.64

Two videos recorded around 7:50 p.m., show a man, whom the New York Times identified as 40-year-old Eberth Mamani Arqui, being shot in the face.65 The forensic ballistics expert report shows that the projectile found in Mamani’s autopsy corresponds to a projectile for a 9mm pistol cartridge.66

Family members told Human Rights Watch that residents of the area told them officers at the police station were firing at protesters and bystanders around that time.67 A video recorded around 8 p.m. shows police officers armed with assault rifles and shotguns about 300 meters west from the corner where the three were shot.68 Another video shared on TikTok at 8:34 p.m. shows police officers on the corner where Mamani Arqui was killed firing 37mm riot guns to the north.69

Human Rights Watch was informed of three other killings on January 9: Elmer Zolano Leonardo Huanca, 16; Ghiovanny Gustavo Illanes Ramos, 21; and Rubén Fernando Mamani Muchica, 53. According to their autopsy reports, reviewed by Human Rights Watch, all victims died from gunshot wounds.70 In Illanes Ramos’ case, the projectile extracted in his autopsy corresponds in size to a rifle bullet approximately 7.62mm in diameter.71

Volunteer medics continued to treat the wounded, following the crowds of protesters into the evening. At around 8 p.m., a group of them attended to at least two people in the Primero de Mayo square, one bleeding from their foot and another from his chest. Although the medics were dressed in blue medical gowns, police officers fired tear gas at them and the wounded moments later, forcing the medics to flee their makeshift health station.

Police tear gassed volunteer medics in Primero de Mayo square after 8 p.m.

At approximately 11 p.m., the Carlos Jorge Medrano hospital issued an official press release reporting that it had received 73 wounded people and 17 dead people.72 On January 10, the hospital updated the figures for the wounded to 112, including 12 with gunshot wounds. Thirty-three remained hospitalized on January 11.73.

Killing of a Police Officer

Twenty-nine-year-old police officer José Luis Soncco Quispe, a member of the Juliaca police who was patrolling by car with another officer in Juliaca on January 9, was also killed that night. A group of people intercepted the officers and forced them out of the vehicle, Peru’s chief of police said.74 Human Rights Watch verified a video shared to Facebook showing a group of roughly 15 people in civilian clothing beating Soncco Quispe by the side of a building 185 meters northeast of Juliaca’s San Martin School, over three kilometers away from the airport and the location of the documented nighttime protests. Another video shows people in civilian clothing attacking the patrol vehicle one block to the southwest. Soncco Quispe died from a blow to the head with “a blunt object,” according to the autopsy.75 His charred remains were found inside the burned patrol vehicle at the location shown in the video. Soncco Quispe’s partner, Ronald Villasante Toque, 23, escaped with a head injury. On March 25, police detained a former police officer and another man whom they accused of committing the killing. Local press said the two men were members of a criminal group.76

Waiting for Justice

Peruvian Attorney General Patricia Benavides told Human Rights Watch that her office had opened 189 investigations into deaths and injuries of protesters and bystanders, and also into acts of violence by protesters, as of February 8, 2023.77 However, Human Rights Watch is not aware of any security force officers who have been arrested for their role in the indiscriminate and excessive force used against protesters in Juliaca on January 9.

Human Rights Watch has identified serious flaws in some of these criminal investigations, including failures to collect precious initial evidence that can compromise the entire investigation. In Juliaca, authorities failed to secure crime scenes and collect bullet casings and other evidence. Also, prosecutors had not taken statements from security officers as of early March, according to the lawyer representing many of the victims in Juliaca.78

Marco Samillán’s sister Milagros, like all relatives of victims Human Rights Watch interviewed, is waiting for those responsible for killing her loved one to be held to account. “We want those who committed these acts to face justice,” she said.79 The families of the victims told Human Rights Watch that they are calling for a diligent and efficient criminal investigation of the events, accountability for the security forces and the current government, and a true commitment to ensure that these events do not happen again.

This page was amended on May 11, 2023 after a witness told Human Rights Watch that she had incorrectly identified one of the people seen in some of the pictures that we published.

May 10, 2023

Human Rights Watch published a 107-page report that addresses the factors that led to the current political and social crisis in Peru and documents disproportionate and illegal use of force and other abuses by security forces, as well as acts of violence by protesters.

Read the report »

More on Human Rights Watch’s work in Peru »

Acknowledgments

We thank the victims’ relatives, witnesses, lawyers, and civil society representatives who made this research possible. They shared their experiences and provided us with photos, videos, and relevant documents. Thanks also to the civilians and journalists who recorded and uploaded videos and photographs of the repression. This documentation enabled Human Rights Watch researchers to report on incidents with a higher level of accuracy and nuance.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with Milagros Samillán, Marco Samillán’s sister, February 14, 2023.

Juan Carlos De Santos Pascual, “Miles de peruanos marchan a Lima para manifestarse contra el Gobierno de Boluarte,” Euronews, January 17, 2023, https://es.euronews.com/2023/01/17/miles-de-peruanos-marchan-a-lima-para-manifestarse-contra-el-gobierno-de-boluarte (accessed on March 8, 2023); Lucia Castro, “Peruanos marchan pidiendo renuncia de presidenta Boluarte y cierre del Congreso,” La República, January 12, 2023, https://www.larepublica.co/globoeconomia/peruanos-marchan-pidiendo-renuncia-de-presidenta-boluarte-y-cierre-del-congreso-3522220 (accessed on March 8, 2023).

Human Rights Watch phone interview with Jaime Borda, Red Muqui, February 1, 2023; Human Rights Watch phone interview with Edwin Poire, February 7, 2023; Poverty in Puno: These are the factors that contribute to social discontent, “Pobreza en Puno: Estos son los factores que contribuyen al descontento social,” RPP Noticias, Januray 11, 2023, https://rpp.pe/economia/economia/pobreza-en-puno-estos-son-los-factores-que-contribuyen-al-descontento-social-noticia-1459517 (accessed on March 8, 2023).

Human Rights Watch phone interview with Milagros Samillán, Marco Samillán’s sister, February 14, 2023.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with a victim’s relative, February 15, 2023. She asked not to be identified; Autopsy conducted by Paul Artemio Mamani, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch; Necropsy diligence certificate conducted by provincial deputy prosecutor Rolando Agramonte Ramos, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch.

“Crisis política y protesta social: Balance defensorial tras tres meses de iniciado el conflicto,” Ombudsperson’s Office report number 190, March 2023, https://www.defensoria.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Informe-Defensorial-n.%C2%B0-190-Crisis-poli%CC%81tica-y-protesta-social.pdf (accessed on April 2, 2023).

Human Rights Watch phone interview with Milagros Samillán, Marco Samillán’s sister, February 14, 2023.

“Pedro Castillo intentó disolver el Congreso y decretar estado de excepción,” La República, December 7, 2023, https://www.larepublica.co/globoeconomia/peru-anuncia-un-golpe-de-estado-despues-de-que-castillo-anuncia-cierre-del-congreso-3504829 (accessed on March 8, 2023).

Lucia Castro, “Pedro Castillo sería acusado por rebelión y conspiración: ¿cuántos años de cárcel recibiría?,” La República, December 8, 2023, https://larepublica.pe/politica/2022/12/08/pedro-castillo-que-son-delitos-de-rebelion-y-conspiracion-por-los-que-fiscalia-podria-darle-hasta-20-anos-de-carcel-atmp (accessed on March 8, 2023); Supreme Court of Justice, File 00039-2022-4-5001-JS-PE-01, January 27, 2023, https://www.pj.gob.pe/wps/wcm/connect/c83497004a303e40bd26fd9026c349a4/ CASTILLO+TERRONES++JOSE+%281%29.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=c83497004a303e40bd26fd9026c349a4 (accessed on March 8, 2023).

“Dina Boluarte juró como nueva presidenta del Perú e hizo un llamado al diálogo,” Infobae, December 7, 2023, https://www.infobae.com/america/peru/2022/12/07/dina-boluarte-juramento-como-nueva-presidenta-del-peru/ (accessed on March 8, 2023); “Pedro Castillo es vacado del cargo y detenido por la Policía luego de intentar golpe de Estado,” Ojo Publico, December 7, 2022, https://ojo-publico.com/ultimas-noticias/3933/castillo-es-vacado-y-luego-detenido-al-intentar-cerrar-el-congreso (accessed on March 8, 2023).

Juan Carlos De Santos Pascual, “Miles de peruanos marchan a Lima para manifestarse contra el Gobierno de Boluarte,” Euronews, January 17, 2023, https://es.euronews.com/2023/01/17/miles-de-peruanos-marchan-a-lima-para-manifestarse-contra-el-gobierno-de-boluarte (accessed on March 8, 2023); Lucia Castro, “Peruanos marchan pidiendo renuncia de presidenta Boluarte y cierre del Congreso,” La República, January 12, 2023, https://www.larepublica.co/globoeconomia/peruanos-marchan-pidiendo-renuncia-de-presidenta-boluarte-y-cierre-del-congreso-3522220 (accessed on March 8, 2023).

“Dina Boluarte dejó de lado el llamado a nuevas elecciones y espera gobernar hasta 2026,” Infobae, December 7, 2022, https://www.infobae.com/america/peru/2022/12/07/dina-boluarte-dejo-de-lado-el-llamado-a-nuevas-elecciones-y-espera-gobernar-hasta-2026/ (accessed on March 8, 2023); Renzo Gómez Vega, “Boluarte presiona al Congreso para adelantar a octubre las elecciones y atajar las protestas en Perú,” El País, January 29, 2023, https://elpais.com/internacional/2023-01-30/boluarte-quiere-adelantar-las-elecciones-en-peru-a-octubre-y-cambiar-la-constitucion-de-1993.html (accessed on March 8, 2023).

Wilber Huacasi, “Por quinta vez el Parlamento archiva adelanto de elecciones,” La República, March 15, 2023, https://larepublica.pe/politica/congreso/2023/03/15/congreso-por-quinta-vez-el-parlamento-archiva-adelanto-de-elecciones-comision-de-constitucion-hernando-guerra-1234560 (accessed on March 20, 2023).

Human Rights Watch phone interview with Jaime Borda, Red Muqui, February 1, 2023; Human Rights Watch phone interview with Edwin Poire, February 7, 2023; Guadalupe Gamboa, “Pobreza en Puno: Estos son los factores que contribuyen al descontento social,” RPP Noticias, Januray 11, 2023, https://rpp.pe/economia/economia/pobreza-en-puno-estos-son-los-factores-que-contribuyen-al-descontento-social-noticia-1459517 (accessed on March 8, 2023).

“Manifestantes intentaron tomar aeropuerto de Juliaca,” RPP Noticias, January 6, 2023, https://rpp.pe/peru/puno/puno-manifestantes-intentaron-tomar-aeropuerto-de-juliaca-noticia-1458494 (accessed on March 8, 2023);”Paro nacional: 16 heridos en Juliaca es el saldo de la violenta jornada de manifestaciones de este viernes,” Infobae, January 7, 2023, https://www.infobae.com/america/peru/2023/01/06/paro-nacional-6-de-enero-en-vivo-minuto-a-minuto-y-ultimas-noticias-de-las-protestas-y-movilizaciones/ (accessed on March 8, 2023).

Radio Exa Asillo, post to Facebook, January 9, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/RADIOEXAASILLOPunoperu/videos/497988452469694 (accessed on February 18, 2023).

Radio Exa Asillo, post to Facebook, January 9, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/RADIOEXAASILLOPunoperu/videos/893517288757978 (accessed February 18, 2023).

“Manual de derechos humanos aplicado a la función policial,” August 14, 2018, p. 39, https://static.legis.pe/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Manual-de-derechos-humanos-policia-nacional-Legis.pe_.pdf

Human Rights Watch interviews with general Víctor Zanabria, chief of the Lima police region, Lima, February 6, 2023.

“Yo apoyo a Pedro Castillo,” post to Facebook, January 9, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/PedroCastilloDelPueblo/videos/1935185210159122 (accessed on March 22, 2023).

Human Rights Watch phone interview with attorney Wilmer Quiroz, March 8, 2023; Criminal file 23-2023 on file at Human Rights Watch; Luz Alarcón C. and Abel Cárdenas, “Cadena de mando: los jefes de la Policía y el Ejército detrás de los planes operativos en la represión de Puno y Ayacucho,” Ojo Público, February 19, 2023, https://ojo-publico.com/4311/los-jefes-policiales-y-militares-la-represion-puno-y-ayacucho (accessed on March 10, 2023).

“Comandante General de Puno y General de la PNP hacen llamado a la paz,” Infobae, January 9, 2023, https://www.infobae.com/america/peru/2023/01/09/comandante-general-de-puno-y-general-de-la-pnp-hacen-llamado-a-la-paz/ (accessed on March 10, 2023); Liubomir Fernández, “Ejército en Puno indica que ya no se usará hondas y huaracas para reprimir a protestantes,” La República, January 3, 2023, https://larepublica.pe/sociedad/2023/01/03/ejercito-en-puno-indica-que-ya-no-se-usara-hondas-y-huaracas-para-reprimir-a-protestantes-lrsd (accessed on March 10, 2023); “Yo apoyo a Pedro Castillo,” post to Facebook, January 9, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/PedroCastilloDelPueblo/videos/1935185210159122 (accessed on March 22, 2023).

“Resolución Suprema Nº 047-2023-in ,” El Peruano, March 18, 2023, https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/aprueban-reasignacion-en-el-cargo-de-diversos-oficiales-gene-resolucion-suprema-n-047-2023-in-2161667-1/ (accessed on April 3, 2023)

Human Rights Watch phone interview with David Arias, journalist, February 10, 2023; Human Rights Watch phone interview with witness and victim’s relative, February 15, 2023. He asked not to be identified for fear of reprisals; Human Rights Watch virtual interview with victim’s family member, February 15, 2023. He asked not to be identified; Human Rights Watch phone interview with witness and victim’s relative, Rosa Luque Mamani, February 20, 2023.

Radio Exa Asillo, post to Facebook, January 9, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/RADIOEXAASILLOPunoperu/videos/729952458369025 (accessed on March 24, 2023)., https://www.facebook.com/diariosinfronteras/videos/701206551588293 (accessed on March 31, 2023).

Human Rights Watch interview with general Raúl Alfaro, then-commander of Peru’s police, Lima, February 7, 2023.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with Milagros Samillán, Marco Samillán’s sister, February 14, 2023.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with Milagros Samillán, Marco Samillán’s sister, February 14, 2023.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with a victim’s relative, February 15, 2023. She asked not to be identified; Autopsy conducted by Paul Artemio Mamani, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch; Necropsy diligence certificate conducted by provincial deputy prosecutor Rolando Agramonte Ramos, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch.

Photos sent to Human Rights Watch by Hugo Curotto Olaechea, photojournalist and stringer for Reuters/AP, January 9, 2023.

Human Rights Watch virtual interview with victim’s family member, February 15, 2023. He asked not to be identified; Public Ministry Forensic Analysis Office, “Informe pericial de balística forense No. 09/2023,” January 23, 2023, signed by Augusto Antonio Bambaren on file by Human Rights Watch.

Max Nina, post to Facebook, January 9, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=10223224974308392&set=pcb.10223224975788429 (accessed on January 10, 2023).

FAMA TV, post to Facebook, January 9, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/famatv27/videos/1581763675603352 (accessed on February 2, 2023).

Autopsy conducted by Julio Wilbert Barrio Nuevo, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch. Public Ministry Forensic Analysis Office, “Informe pericial de balística forense No. 09/2023,” January 23, 2023, signed by Augusto Antonio Bambaren on file by Human Rights Watch.

Max Nina, post to Facebook, January 9, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=10223224975068411&set=pcb.10223224975788429 (accessed on January 10, 2023).

“Manual de derechos humanos aplicado a la función policial,” August 14, 2018, p.39, https://static.legis.pe/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Manual-de-derechos-humanos-policia-nacional-Legis.pe_.pdf.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with Mauro Cayo Sacaca, February 20, 2023. Autopsy conducted by Paul Artemio Mamani, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with Edgar Jorge Huarancca Choquehuanca’s uncle, Pedro Luque, February 15, 2023. The autopsy concluded he sustained three gunshot wounds. Autopsy conducted by Milton Edgar Condori, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch; Public Ministry, Forensic Analysis Office, “Informe pericial de balística forense No. 07/2023,” January 23, 2023, signed by Augusto Antonio Bambaren, on file at Human Rights Watch.

Photo shared with Human Rights Watch by Hugo Curotto Olaechea, photojournalist and stringer for Reuters/AP, January 9, 2023.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with victims’ relative, February 14, 2023. She asked not to be identified.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with victims’ relative, February 14, 2023. She asked not to be identified; Autopsy conducted by Paul Artemio Mamani, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with victim’s relative, February 17, 2023. He asked not to be identified; Autopsy conducted by Milton Edgar Condori, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch; A video verified by Human Rights Watch shows him on the ground past the airport’s fence.

Autopsy conducted by Milton Edgar Condori, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch; Public Ministry Forensic Analysis Office, “Informe pericial de balística forense No. 08/2023,” January 23, 2023, signed by Augusto Antonio Bambaren, on file at Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with Marcos Quispe Quispe’s daughter Vilma Quispe February 17, 2023.

Autopsy conducted by David Chuquipoma Pacheco, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch; Public Ministry Forensic Analysis Office, “Informe pericial de balística forense No. 05/2023,” January 23, 2023, signed by Augusto Antonio Bambaren, on file at Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with victim’s relative, February 15, 2023. He asked not to be identified for fear of reprisals. Autopsy conducted by David Chuquipoma Pacheco, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch.

Public Ministry, Forensic Analysis Office, Forensic Ballistics Expert Report, “Informe pericial de balística forense No. 05/2023,” January 23, 2023, signed by Augusto Antonio Bambaren, on file at Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with victim’s relative, February 15, 2023. He asked not to be identified for fear of reprisals.

SIG Sauer states their SP2022 handgun uses ”9mm Luger” rounds, which are the same as 9x19mm Parabellum rounds. SP2022 Nitron Carry, SIG Sauer, https://www.sigsauer.com/sp2022-nitron-carry-size.html (accessed on April 4, 2023); ”Sig Sauer será el proveedor de pistolas 9 mm para la Policía de Perú,” Infodefensa, December 9, 2015, https://www.infodefensa.com/texto-diario/mostrar/3132639/sig-sauer-sera-proveedor-pistolas-9-mm-policia-peru (accessed on April 4, 2023).

Human Rights Watch phone interview with victim’s relative, February 15, 2023. She asked not to be identified; Autopsy conducted by David Chuquipoma Pacheco, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch verified a video shared on Twitter and two photographs uploaded to Facebook that show Heliot Cristhian Aricaza 50 meters east of the airport bleeding from a wound to his neck and being carried away to the south; Human Rights Watch phone interview with Aricaza’s mother Rosa Luque Mamani, February 20, 2023; Autopsy conducted by Feliz Uscamayta Chipana, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch.

“Homicidios en Juliaca,” IDL-Reporteros, April 9, 2023, video clip, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eV_s0t0KYg4 (accessed on April 10, 2023).

Autopsy certificate signed by Yuriza Karol Neyra Flores on January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch.

“How Peru Used Lethal Force to Crack Down on Anti-Government Protests,” The New York Times, March 16, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/16/world/americas/peru-protests-police.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare (accessed on March 17, 2023).

Public Ministry Forensic Analysis Office, “Informe pericial de balística forense No. 06/2023,” January 23, 2023, signed by Augusto Antonio Bambaren, on file at Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch phone interview with Brayan Apaza Jumpiri’s mother, Asunta Jumpiri Olvea, February 17, 2023; Human Rights Watch phone interview with Paul Franklin Mamani Apaza’s father, Mateo Mamani Tito, February 17, 2023.

@coaquirapablo, post to TikTok, January 9, 2023, https://www.tiktok.com/@coaquirapablo/video/7186827278523845894 (accessed on February 2, 2023).

@charoch19, post to TikTok, January 9, 2023, https://www.tiktok.com/@charoch19/video/7186830925446040837 (accessed on March 17, 2023).

Autopsy conducted by David Chuquipoma, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch; Autopsy conducted by Paul Artemio Mamani, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch; Autopsy conducted by Yuriza Karol Neira Flores, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch; Autopsy conducted by Yuriza Karol Neira Flores, January 10, 2023, on file at Human Rights Watch.

Public Ministry Forensic Analysis Office, “Informe pericial de balística forense No. 04/2023,” January 23, 2023, signed by Augusto Antonio Bambaren, on file at Human Rights Watch.

Carlos Jorge Medano Hospital, post to Facebook, January 10, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/HospitalCarlosMongeMedrano.Oficial/photos/pcb.1918847415136115/1918884881799035/ (accessed on March 8, 2023).

Red Salud San Román, post to Facebook, January 11, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=487427973571711&set=pcb.487428456904996 (accessed on March 8, 2023).

Human Rights Watch interview with General Raúl Alfaro, then-commander of Peru’s police, Lima, February 7, 2023.

“Informe Pericial de Necropsia Médico Legal Número 019-2023,” Public Ministry, no date, on file at Human Rights Watch.

“Expolicía está implicado en crimen de suboficial calcinado en Juliaca,” La República, March 24, 2023, https://larepublica.pe/sociedad/2023/03/24/puno-expolicia-esta-implicado-en-crimen-de-suboficial-calcinado-en-juliaca-protestas-9-de-enero-lrsd-783816 (accessed on March 30, 2023).

“Crisis política y protesta social: Balance defensorial tras tres meses de iniciado el conflicto,” Ombudsperson’s Office report number 190, March 2023, p. 41; Human Rights Watch interview with Peru’s attorney general, Patricia Benavides, Lima, February 8, 2023. The attorney general’s office had not responded to a request from Human Rights Watch to specify how many investigations were for possible abuses by security forces and how many for violence by protesters, as of March 28, 2023. However, the Ombudsperson’s Office reported the attorney general’s office had opened 105 investigations into crimes by protesters, such as disobedience to authority, rioting, and disturbing public order.