Two years since President Nayib Bukele announced a “war against gangs” in El Salvador, the country has gone through rapid change.

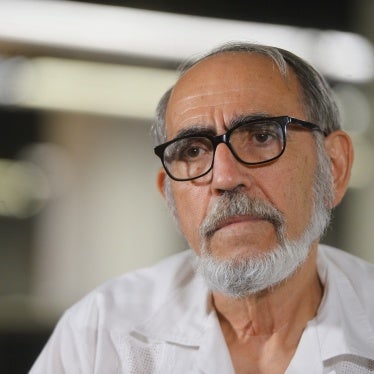

Agustín, not his real name, was 16 when Bukele made the announcement. When Human Rights Watch researchers met him a year-and-a-half later he had already personally experienced the country’s quick turn from being gang-ridden to, increasingly, a police state.

Agustín first suffered from gang violence in Cuscatancingo, a few kilometers north of the capital. As in many areas in El Salvador, gangs controlled his neighborhood, and many aspects of his family’s lives. “It was suffocating,” his mother told us. “You had to think about what to say, how to walk and what to wear. They saw everything. It was like being with your enemy 24 hours.”

The MS-13, one of El Salvador’s most prominent gangs, tried to recruit her son when he was 12. Five adolescent gang members promised him better shoes, clothing, and cigars. Many boys from the neighborhood joined, he said, but he refused.

The gangs have recruited thousands of children. Studies show mostly join these criminal groups between ages 12 and 15. A lack of educational and economic opportunities makes it easier for gangs to recruit them, even in exchange for shoes and cigars.

Violence took a turn for the worse for Agustín in June 2021. MS-13 gang members beat his stepfather and threatened to kill his mother, a community leader, after she helped police distribute food during the Covid-19 pandemic. “Talking to the police or a soldier was like a death sentence,” she said.

The violence forced the family to flee to Mejicanos, a city near San Salvador. They escaped the immediate threat but did not find safety. The 18th Street gang, the country’s second largest, controlled their new neighborhood. A few months later, they threatened to kill Agustín’s mother, forcing the family to leave again.

In January 2022 they tried to find peace in San José Guayabal, a small town largely untouched by gang presence. They even became hopeful about their country when in March, President Bukele launched his “war against gangs” and his supporters in the Legislative Assembly declared a state of emergency, suspending basic rights.

Yet a few months later, police officers and soldiers appeared at his house to arrest Agustín and his stepfather. Officers did not provide a warrant or a reason for the arrest. They said they were taking him, then 16, to a police station to “investigate him.”

He is one of 2,800 children sent to jail since the state of emergency began. What followed for him, as in many other cases human rights groups in El Salvador documented during the emergency, was a harrowing sequence of abuses.

He told us that soldiers simulated his execution on a deserted road as they were transferring him between police stations. One soldier laughed, as he triggered a gun to his head, he said. Then they reportedly told him to run away, with his feet cuffed.

He said he was held, for several days, in an overcrowded cell, where 70 children shared three beds. He recalls being forced to sleep on the floor. Guards did nothing when other detainees kicked him, virtually every day, while they counted the seconds out loud, always up to 13—an apparent reference to the MS-13.

As with most of the 78,000 people detained during the “war against gangs,” prosecutors accused him of “unlawful association,” the crime of belonging to a gang, which does not require proving the defendant has committed a violent or other unlawful act. The crime is defined so broadly under El Salvador’s law that anyone who has interacted with gang members, willingly or not, may be prosecuted.

The judge in his case found no evidence against him and released Agustín after 12 days. But police and soldiers, who have overbroad powers and little to no oversight in El Salvador, kept insisting that he was a gang member. Some harassed him in the local park, beating him and threatening to arrest him again.

He left school and took a construction job in another city. When Human Rights Watch met him, the gangs that had long tormented his family were no longer his biggest concern. Homicides in the country have dropped significantly and gangs appear to be weakened, for now. But as his mother told us, he “now cries every time he sees soldiers or police.”

Salvadorans should not be forced to choose between living in fear of gangs or of security forces. They should be offered a brighter future, one in which the government protects children from violence and abuse and minimizes the risk of gang recruitment by ensuring children have the educational and other support they need. One in which law enforcement conducts meaningful investigations to identify real gang members—and dismantle their groups—instead of relying on arbitrary arrests and abusive treatment.

“We want to leave El Salvador,” his mother told us. “I want my child to forget everything.”