Outside the camps, throughout Xinjiang, Turkic Muslims face arbitrary arrest and surveillance by the authorities. Their passports are confiscated, and they are required to attend flag-raising ceremonies and meetings where they denounce their families and praise the Party. Human Rights Watch interviews researcher Maya Wang about what she learned speaking with former detainees and people whose relatives live in Xinjiang.

What is happening in Xinjiang?

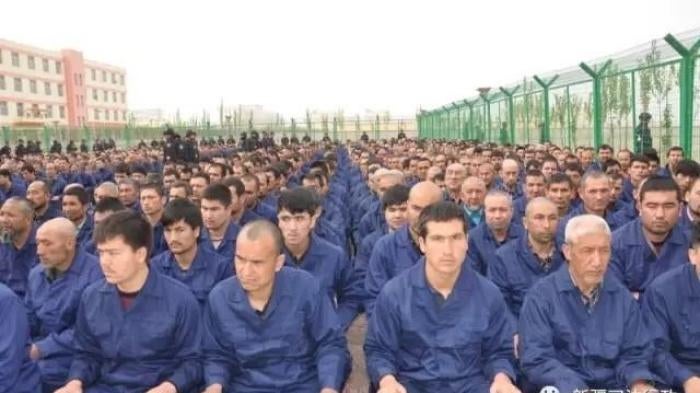

The Chinese government is carrying out a large-scale repression of Turkic Muslims, who are primarily ethnic Uyghurs and Kazakhs. The authorities have sent many to political education camps in Xinjiang. In addition to singing propaganda songs and learning Mandarin Chinese, which is not their native language, Turkic Muslims are forbidden from saying “As-Salaam-Alaikum,” [an Islamic greeting, meaning “peace be unto you”] and must say hello in Mandarin instead. If they resist, or officials deem they have failed their lessons, they are punished. They may be subjected to solitary confinement, not be allowed to eat for a certain period, or required to stand for 24-hour periods, among other punishments.

The political education camps are just one part of the crackdown. Turkic Muslims are also being held in detention centers and prisons. Official figures suggest a three-fold increase in formal arrests in Xinjiang in the past five years.

The repression also has an impact outside of China. Many ethnic Uighurs and Kazakhs live abroad, and the crackdown has been tearing families apart. Some family members may be held in Xinjiang and cannot leave because authorities have confiscated their passports, or they have been detained, and the other part of the family is outside of China. People have not been able to communicate with each other.

Why has the level of repression increased in recent years?

In late 2016, Party Secretary Chen Quanguo moved from Tibet to Xinjiang. In Tibet, he instituted a number of repressive policies, some of which, including deploying tens of thousands of government and party officials across the region, have since been replicated in Xinjiang. The Chinese government already tightly controls the practice of religion throughout China. What we’re seeing in Xinjiang is China’s senior leadership persecuting an ethnic and religious minority.

Why have Turkic Muslims been sent to political education camps?

Chinese authorities have targeted people with connections to a list of “26 sensitive countries,” including Kazakhstan, Turkey, and Indonesia. For example, someone who has visited Turkey for two weeks could be targeted. They have also targeted people who have communicated abroad using cell phone applications like WhatsApp. Others have been sent to political education camps for having a beard, since facial hair is banned. But there’s no legal justification to hold anyone in political education camps, as they have not been charged or convicted of crimes.

How long do detainees spend in a political education camp?

The detainees we spoke with spent several months in the camps. They were told they would be there for 10 days, or 3 months, or 6 months, and that once they completed the so-called education program, they would be able to leave. But there is no telling when anyone is going to be released. There is no formal procedure.

Does the Chinese government acknowledge the existence of these camps?

Domestic state media reports and government documents do talk about these camps. They explain that these camps are necessary to cure the minds of Turkic Muslims who have an “ideological illness.”

However, internationally, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has repeatedly denied that political education camps exist, and in a United Nations review of human rights in China in August, officials portrayed these facilities as benevolent vocational training centers. This is false – our research confirmed other findings that people are being held against their will.

How does the government justify sending people to political education camps?

The government says there is a problem of terrorism and extremism in Xinjiang, and that the “extreme thoughts” of Turkic Muslims need to be cured. The government claims to be carrying out a “civilizing mission” for Turkic Muslims.

The government has adopted a very broad and vague definition of terrorism. There have been a number of violent incidents in Xinjiang and other parts of China, but it is hard to independently verify what happened because the Chinese government controls this information. The government adopted a “Strike Hard Campaign” ostensibly to combat terrorism, but instead the authorities used its broad mandate to punish and control Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang without regard to basic rights.

What other repressive policies have been implemented in Xinjiang, outside the camps and detention facilities?

Conditions outside detention facilities have a striking resemblance to those inside. Movement is restricted. The impact on people’s lives and their families has been devastating. The authorities punish anyone who contacts people abroad. Turkic Muslims must apply for permission to leave their local area if they want to visit their families, or even to see a doctor. Authorities have also required people to return their passports for “collective safekeeping.” Some people who have left Xinjiang but returned for visits – are now stranded there.

One woman left Xinjiang to pursue further education. She brought one child with her, and she left her other two children with her parents, believing that in a few months she would bring them over. But since authorities recalled passports, her children are now in Xinjiang and she hasn’t been able to get in touch with them for over a year. She doesn’t know what’s happened to her parents. She’s heard that children are forcibly sent to orphanages, separated from caretakers if caretakers are deemed politically unreliable.

Neighbors are encouraged to spy on each other and they are watched by local officials. They are also watched by mass surveillance systems. Within Xinjiang, there are countless checkpoints with facial recognition cameras. Homes have QR codes near the front door, so officials can scan the codes to make sure the people in the home are supposed to be there. The authorities are also collecting biometrics on a mass scale, even from children. As part of the “Becoming Family” campaign, party officials spend at least five days every two months in the homes of Xinjiang residents, primarily those living in the countryside.

The government has heightened religious restrictions – practicing Islam has effectively been outlawed. During the Muslim holiday of Ramadan, local officials monitor homes for anyone who might be turning on the lights early in the morning for the pre-dawn meal that Muslims eat before they fast for the day. Mosques have been closed, converted for other purposes, or demolished. Authorities are confiscating prayer mats and asking people how many times a day they pray.

The Chinese government is also harassing some Turkic Muslims abroad, forcing them to return to China and threatening to harm their families if they don’t.

What is the human toll of the government repression?

The people we interviewed outside of China expressed great concern for their family members suffering back in China. In some cases, they have been told by officials to return to Xinjiang and decided with apprehension to go back. One man said, “I’m not sure if I’m going to come out alive, but I’m going to go back home because I’m worried about my family back home.” It’s really heartbreaking, and many said they suffer great distress and have had suicidal thoughts. Desperate financial situations compound the stress.

One woman said, “It’s minus 30 degrees in winter and I have three children and one of them is sick now. I used up all my money to pay for his medication and I’m sick now. I don’t have money to keep the heater going but if I turn it off the kids will freeze.” Her husband is in a camp because of his link to her, generating feelings of guilt, along with her inability to provide for her children. It’s horrible that someone would have to make these choices, when none of these people are even accused of crimes.

How did you conduct this research?

We interviewed 58 people, five of whom were former detainees in political education camps or detention centers. Over a dozen of them left Xinjiang after January 2017, meaning that they’ve experienced the crackdown under Party Secretary Chen Quanguo. The others are family members of people who are currently detained or who are unable to leave Xinjiang because their passports have been confiscated.

We only spoke with people who have left Xinjiang because we didn’t want to endanger people inside Xinjiang. The government does not permit our access to the region and trying to interview people there would put them at risk. We also analyzed many official documents and state media reports.