Australia’s relationship with China has been tumultuous of late: political scandals, security threats, a perceived need for draconian new legislation, angry rhetoric from Beijing. It’s not a surprise that officials, including members of the new Australian government, and ordinary people across Australia have struggled to find the right answers to a complex and charged relationship.

But as Australia tries to strike a balance between benefiting from and being threatened by its relationship with Beijing, a key piece of solving this puzzle has largely dropped out of the debate: pressing for better respect for human rights inside China.

Since coming to power in 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping and his government have directed the most pervasive rollback on rights since the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre. China has adopted a slew of laws on national security, cyber-controls, and civil society that further restrict everything from the right to a fair trial to privacy rights to freedom of expression and association. Authorities have increased deployed mass surveillance technology to stamp out perceived dissent, and directed particular hostility at ethnic and religious minorities: hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs, an ethnically Turkic Muslim minority, are currently being arbitrarily detained for “political education” without a legal basis for doing so.

Not content to limit human rights at home, Chinese authorities have taken their repressive policies global. Human Rights Watch has documented concerted efforts by China to undermine key United Nations human rights mechanisms, limiting the ability of independent voices—even those not focused on China—from making use of these global arenas. China is launching its own rights-free institutions, like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and skillfully manipulating existing ones, such as Interpol, to carry out abuses.

The Chinese Communist Party is so confident in its global hunt for corruption suspects that Chinese police and party “discipline” officials go to countries such as Australia to intimidate their targets into returning—and without informing local law enforcement. Threats to free inquiry on university campuses worldwide are now painfully clear to the Australian public.

Australia’s response to these developments has been at best perfunctory. It opted to confine most of its human rights concerns through an official bilateral dialogue which, like most others, was virtually invisible to those who need to see the outside world defending their human rights: activists and ordinary people across China. Those dialogues also suited Chinese officials intent on keeping the discussion contained and out of high-level meetings. China began pressing to downgrade the dialogue around 2014, and a round hasn’t been held since (a fact that seems to have escaped former Foreign Minister Alexander Downer, who once heralded these dialogues).

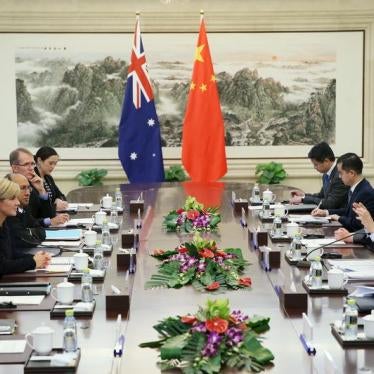

From time to time Australia has joined - but not led - critically important, coordinated international interventions, including an unprecedented joint statement on the crackdown against activists and lawyers at the March 2016 United Nations Human Rights Council, and a joint letter calling for an end to Beijing’s abuses of human rights lawyers in March 2017. Former foreign minister Julie Bishop’s March 2017 Singapore speech suggested she was taking a tougher position on China’s lack of democratic rule. And Australian diplomats in China do try to monitor political trials and meet with human rights defenders.

But has Australia weighed in consistently with China to defend the values it says it cherishes on the occasions when it’s needed most? Quite simply: no.

When Liu Xiaobo, an imprisoned Chinese literary critic, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, then-opposition leader Bishop penned an editorial calling for him to be allowed to attend the Oslo ceremony. When Liu died in state custody in 2017, she issued the tersest of statements.

Indeed, it is hard to remember the last time senior Australian diplomats said anything publicly about justice for the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre, or publicly challenged Chinese leaders over their abuses of human rights defenders. Earlier this year China proposed a resolution at the Human Rights Council that threatens key elements of international human rights law and norms - leaving decisions to states, squeezing out independent civil society, rejecting discussion of accountability. Australia abstained.

Even in the high-octane debate about Chinese political interference in Australia, Canberra focused narrowly on concerns about espionage, registering “foreign agents”, and restrictions on foreign funding to political parties and “political” organisations. Less attention has been paid to intimidation of critics and members of the diaspora in Australia - and less still has been devoted to mitigating some of these problems at their root in China. If the Chinese Communist Party wasn’t so intent on censoring criticism and imposing its views worldwide, there might not be concerns about threats to academic or press freedom in Australia. If China had a credible, independent legal system, Australia would likely face far fewer headaches over trade—or over cases like Stern Hu or Feng Chongyi.

Recently Beijing blinked in the face of relentless public and private diplomacy, and finally released Liu Xia, Liu Xiaobo’s widow who had been held under house arrest for eight years, and let her leave the country. Her release demonstrates that values-based interventions on human rights can produce the desired result.

China’s human rights abuses do not stem from a lack of robust Australian interventions, but the Australian government’s half-hearted pressure has helped embolden the Chinese government. It is encouraging to see Australia reject a role for problematic Chinese firms like Huawei and ZTE as threats to security, and to hear new Foreign Minister Marise Payne state that Australia’s greatest challenges come from countries - including China - that do not follow the rules-based international order.

But there’s far more for Australia to do. It can demonstrate the commitments articulated in its role as a member of the UN Human Rights Council by consistently raising concerns about human rights abuses in China, and threats posed by China to the UN human rights system. It can pivot from the Huawei decision to ensure that Australian companies operating in China do so in conformity with the UN principles on business and human rights. The new government should prioritise ensuring that Australians live free of fear of Chinese government or Communist Party intimidation. And Foreign Minister Payne and others should in all high-level meetings with Chinese counterparts unambiguously challenge China’s human rights violations, which threaten that international rules-based order.

At this moment it couldn’t be clearer that China’s and Australia’s human rights realities are increasingly intertwined. The question is whether Australia will face that challenge squarely and fight for everyone’s rights.