(Berlin) – Turkish authorities have detained and prosecuted large numbers of people in recent weeks over social media posts criticizing Turkey’s military operation in the northwest Syrian district of Afrin, Human Rights Watch said today. The crackdown violates the right to peaceful expression.

According to the Turkish Interior Ministry, authorities detained 648 people between January 20 and February 26, 2018, over social media posts criticizing Turkey’s military operations in Afrin. Authorities held another 197 people for expressing criticism in other forms, including street protests or expressing solidarity with protesters on social media. The Interior Ministry has indicated that more criminal investigations have been opened since the end of February.

“Detaining and prosecuting people for tweets calling for peace is a new low for Turkey’s government,” said Hugh Williamson, Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “Turkish authorities should respect people’s right to peacefully criticize any aspect of government policy, including military operations, and drop these absurd cases.”

This most recent social media crackdown has targeted a wide range of people, affecting journalists; human rights activists; politicians, including four members of parliament from the pro-Kurdish HDP opposition party; members of nongovernmental organizations; academics; construction workers; physicians; and high school and university students.

Human Rights Watch has examined in detail five cases of criminal investigations and prosecutions over tweets related to Afrin, involving a journalist, a politician, a documentary maker, an LGBT activist, and a member of a human rights organization, as well as one conviction of a physician for an earlier case of nonviolent speech on social media. Human Rights Watch examined interrogation protocols, indictments, and court rulings, and interviewed three people who are under criminal investigation for sharing nonviolent content on social media, as well as 10 human rights lawyers working on social media cases.

After examining the cases, Human Rights Watch believes that some of the police raids and criminal investigations are being used as a form of punishment rather than out of genuine belief that criminal behavior has occurred. Even if a case does not go to trial or ends in acquittal, people labeled as terrorism suspects face adverse consequences due to police investigations and criminal proceedings, including possible loss of employment and social exclusion.

On February 7, Harlem Désir, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s representative on media freedom, criticized the detention of hundreds of social media users for their opposition to the Afrin operation as “unacceptable.” The European Parliament condemned Turkish authorities’ repression of dissenting views on the military incursion in a resolution on February 8.

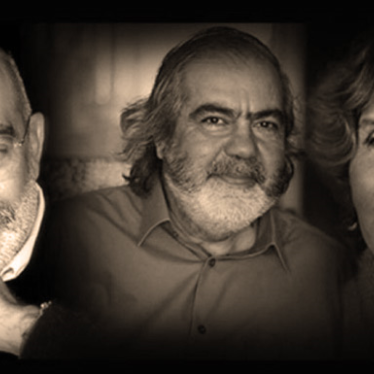

In addition to police action over social media posts relating to the Afrin operation, the police have targeted people and groups for publishing statements and organizing news conferences to protest the offensive. They include 11 senior members of the Turkish Medical Association (TTB), including its chairman, Raşit Tükel; Mithat Can, the 73-year-old head of the Hatay branch of the Human Rights Association (IHD); and senior members of the rights group People’s Houses, including its co-chair, Dilşat Aktaş, all of whom are currently under criminal investigation.

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly criticized the arbitrary use of overbroad antiterrorism legislation in Turkey to punish nonviolent activities, including critical writing and online activism, in violation of the right to freedom of expression. Human Rights Watch research has also found that investigations and prosecutions for terrorism-related offenses in Turkey often lack concrete evidence and fail to adhere to due process.

The criminalization of peaceful speech on the internet has a chilling effect on social media use and has led to increased self-censorship. According to a 2017 report by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, the use of Facebook and Twitter in Turkey have both declined, possibly due to fears of government surveillance. Some of those Human Rights Watch interviewed said that people in Turkey now think twice before posting or reacting to online content criticizing the government.

According to transparency reports published by Twitter, Turkey was the world leader in requests to remove accounts or content – so-called “take down” requests – between 2014 and mid-2017. According to the nongovernmental organization Freedom House, internet freedom in Turkey has steadily deteriorated, with its Freedom Net Overall Score slipping by 21 points, from 45 in 2011 to 66 in 2017, with the higher score meaning more violations.

“There is no justification for Turkish authorities using the criminal justice system against peaceful critics,” Williamson said. “The Turkish government needs to tolerate dissenting views in society, even if they are sharply opposed to its own.”

Activists Prosecuted for Social Media Posts

Nurcan Baysal, a journalist and human rights activist, is on bail awaiting trial on charges of “inciting hatred and enmity among the population” for posting a number of tweets criticizing the Turkish military incursion into Afrin on her personal Twitter account. If convicted, she faces up to three years in jail. None of the eight tweets listed in the indictment, seen by Human Rights Watch, promote or incite violence. On the contrary, the posts criticize war and the use of violence. Baysal, who spent three days in police custody, described the late-night raid on her house when she was detained:

Despite the fact that I was visible from the outside – I was watching TV at the time – they tried to break in the door without ringing the doorbell. About 20 policemen entered my house wearing masks and trained their automatic rifles on me.

Mehmet Türkmen, deputy head of the Labor Party of Turkey (EMEP), a leftist political party with no seats in Parliament, was detained at the airport in Gaziantep by anti-terror police on January 28 over a January 20 Facebook post in which he stated his opposition to the Afrin offensive. His post, illustrated with a photograph of a street demonstration in the city of Afrin and of a TV screen showing Turkish coverage of the military operation, does not promote violence in any way. The post ends with: “Everyone in Turkey and the region who is on the side of friendship between peoples and peace has to say ‘No’ to this war.” He was arrested on January 31, facing charges of “spreading propaganda for a terrorist organization.” He remained in detention pending trial as of March 26.

Ali Erol, a well-known LGBT rights activist, was among 16 people detained in Ankara on February 2 for their online criticism of the Afrin military operation. Erol is co-founder of the Ankara-based LBGT rights group Kaos GL. The police questioned Erol about one tweet and two retweets, none of which promoted violence. The tweet, posted on his timeline on January 21, shows a picture of a poster reading “Shame on you,” hung in an olive tree, a reference to the official Turkish name of the Afrin offensive, “Operation Olive Branch.” Above the picture Erol had listed the hashtags: “NOToWarInAfrin,” “NoToWar,” and “Olive.” He is being investigated for “propaganda for a terrorist organization” and “inciting hatred and enmity among the population.” He was conditionally released after five days in police custody. The Fifth Ankara Peace Court imposed a travel ban and required him to sign in at his local police station every Monday. One of Erol’s lawyers told Human Rights Watch that during the time Erol spent in police custody, the police took no action to collect additional evidence:

There was no reason for Ali Erol to remain in police custody for five days. This leads me to believe that the custody itself is used to intimidate and punish people for criticizing the military operation in Afrin.

Sibel Tekin, a documentary filmmaker, was detained on February 2 in a morning raid on her Ankara home on accusations of terrorism propaganda. The police questioned Tekin about four tweets and five retweets, made from the shared Twitter account of a citizen journalist video collective she has occasionally been involved in. The tweets, none of which promoted violence, for the most part reported on police repression of peaceful protests against the Afrin offensive and on detentions of protesters. Other tweets included critical analyses of the military incursion. Tekin did not write any of the Twitter posts she was questioned over. She was released under judicial supervision on February 5.

Kutay Meriç, an executive member of People’s Houses (Halk Evleri), a human rights group, was detained on February 13 during a police raid on his home in Antalya over several of his Facebook posts criticizing the military operation in Afrin, none of which promote or praise violence. Seven days later the First Antalya Peace Court ordered his pretrial detention on charges of “propaganda for a terrorist organization.” He was later released pending trial on February 28.

Others subject to criminal investigation over social media posts on Afrin include at least four members of parliament from the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). Turkish media reported that the head prosecutor in Ankara has announced criminal investigations against the four for their social media posts criticizing the Afrin operation. On March 7, the Ankara head prosecutor sent applications to the Justice Ministry to investigate three more of the party’s parliament members for “terrorism propaganda” via their social media accounts.

Social Media Crackdown

Turkey has a long tradition of misusing the criminal justice system and overbroad terrorism laws to prosecute journalists, activists, and other government critics. Prosecutors have repeatedly applied articles of the law such as, “inciting hatred and enmity among the population,” and “spreading terrorist propaganda” to intimidate and silence peaceful dissent both on- and offline.

Due to sustained government attacks on independent and critical media, Turkish citizens have increasingly taken to social media to get and share information, which in turn has prompted increased online surveillance and censorship by the authorities.

The recent detention and prosecution of online critics intensifies a crackdown on freedom of speech online that has been going on for several years. Internet censorship also has an extended history in Turkey. Human Rights Watch has documented the arbitrary and disproportionate blocking of entire websites in violation of the right to freedom of speech and the right to access information online. Following the start of Turkey’s military operation in Afrin on January 20, peaceful speech on social media has become the main target for arbitrary terrorism charges and criminal investigations.

The northwest Syrian district of Afrin is under the control of the Syrian Kurdish political party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), and their armed forces, the People’s Protection Units (YPG), which the Turkish government regards as a terrorist organization. On March 18, the Turkish government claimed that it had taken control of Afrin city.

Human Rights Watch interviews with lawyers suggest that people who make critical statements on social media are increasingly being investigated for an alleged “membership of an armed terrorist organization,” rather than association or propaganda offenses, with the evidence cited against them consisting of nothing but their opinions expressed on social media, shared use of hashtags, or the fact that they are part of the same civil society group. Suspects under investigation on charges of membership in armed organizations are more frequently placed in pretrial detention, due to the gravity of the charge, and face longer sentences if found guilty.

A prominent human rights defender and medical doctor, Ömer Faruk Gergerlioğlu, was sentenced by the 2nd Kocaeli Heavy Penalty Court to two years and six months in prison on February 21 for social media posts about the Kurdish issue and the breakdown of the peace process in 2015. He has appealed the verdict.

The evidence cited against him consisted of several posts promoting an end to the Turkish-Kurdish conflict and demanding peace on his social media accounts in 2016. None of them advertised or encouraged violence. The one tweet cited in the detailed ruling, seen by Human Rights Watch, consisted of a link to a news article published on the Turkish online news website T24 illustrated with a photograph of three armed PKK militants and headlined: “PKK: If the government takes a step forward, peace will come in one month.” The judge listed the headline and the photograph, both editorial choices made by T24, as reasons for a terrorism propaganda conviction. The detailed ruling also falsely identifies Gergerlioğlu as the author of the article.

Gergerlioğlu was the subject of an intense smear campaign by pro-government media during the criminal investigation and trial, and was dismissed from his job at the Izmit Seka State Hospital before his conviction. Gergerlioğlu told Human Rights Watch: “I have always promoted peace. During the peace process I was praised by the government for saying this, and now I was turned into a criminal for still saying the exact same things.”