The Libyan government should release without conditions ailing political prisoner Fathi al-Jahmi, who remains in state custody despite recent reports of his discharge, Human Rights Watch and Physicians for Human Rights said in a joint statement today.

Al-Jahmi’s health is improving after better medical care in recent months at a state-run hospital in the capital Tripoli, Human Rights Watch and Physicians for Human Rights said, but he is considerably sicker than at the time of his arrest four years ago. He was detained in March 2004 after calling for a free press and free elections in Libya.

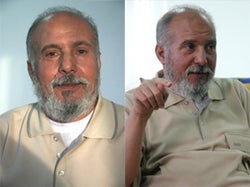

Top: Fathi al-Jahmi at an Internal Security Agency facility in Tripoli on May 10, 2005. Bottom: Fathi al-Jahmi at the Tripoli Medical Center, March 13, 2008. © Fred Abrahams/Human Rights Watch |

Representatives of Human Rights Watch and Physicians for Human Rights visited al-Jahmi, 66, at the hospital in mid-March 2008 and spoke privately with him, his family, and his doctor, as state security officers stayed outside the room. The visit was facilitated by the Qadhafi Foundation, run by Mu`ammar al-Qadhafi’s son, Saif al-Islam.

“We’re glad al-Jahmi’s health is improving, but dismayed he’s not yet free,” said Fred Abrahams, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch who met al-Jahmi in Tripoli. “He should be able to leave the hospital and seek medical care of his choice, either in Libya or another country.”

Despite recent improvements, al-Jahmi’s health had substantially worsened following his March 2004 arrest, Human Rights Watch and Physicians for Human Rights said.

“There’s no doubt that negligent care contributed to the serious deterioration of al-Jahmi’s health during his early detention,” said the doctor who examined him, Dr. Scott Allen, an adviser to Physicians for Human Rights and co-director of the Brown University Center for Prisoner Health and Human Rights. “Even though his health improved in the last few months, he remains very ill. He’s stable and can be treated as an outpatient.

As of March 28, al-Jahmi remained in the Tripoli Medical Center and security officers were controlling access to visitors. Al-Jahmi’s hospitalization under guard stems from a May 2006, court decision, which determined him mentally unfit for trial and ordered him detained at a psychiatric hospital. The authorities failed to make the hearing or the decision public, or to inform the family. Human Rights Watch and Physicians for Human Rights asked for, but have not yet received, a copy of the court’s order, as well as al-Jahmi’s full medical records.

During the roughly one year al-Jahmi spent at the psychiatric hospital, his health significantly declined, forcing his transfer to the Tripoli Medical Center in July 2007. Al-Jahmi told Human Rights Watch and Physicians for Human Rights that during his detention in the psychiatric hospital the authorities denied him access to needed medications and a doctor, as well as family visits.

According to the family, they had no information on al-Jahmi’s whereabouts during this time.

On March 13, 2008, Allen conducted a thorough examination of al-Jahmi, in private, in his room in the Tripoli Medical Center. He reviewed al-Jahmi’s medical records and concluded that his health had improved in recent months, apparently after the intervention of the Qadhafi Foundation. Al-Jahmi’s health had deteriorated badly, apparently due to improper treatment and denial of medications.

This medical examination was a follow-up to a February 2005 check-up conducted by a doctor from Physicians for Human Rights and the International Federation of Health and Human Rights Organizations. At the time, the doctor received assurances that al-Jahmi would receive proper medications and medical care. Human Rights Watch received the same assurances during a visit to al-Jahmi in May 2005.

Al-Jahmi suffers from diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, Allen said. According to al-Jahmi’s doctors, he was experiencing severe heart failure at the time of his transfer from the psychiatric facility to Tripoli Medical Center in July 2007. On admission, an echocardiogram showed a dangerously impaired heart muscle.

Despite the recent improvements, significant and pressing health problems remain, Human Rights Watch and Physicians for Human Rights said.

“Mr. al-Jahmi is in urgent need of a cardiac catheterization to evaluate ongoing heart disease,” Allen said. “While Tripoli Medical Center appears well-equipped for this procedure, there is impaired trust in an environment of state control.”

Human Rights Watch and Physicians for Human rights said they left Libya with the distinct impression that al-Jahmi and his family were not free to make independent decisions about his medical care due to real or perceived pressure from the government. The real or perceived pressure is detrimental to adequate care and taints the principle of informed consent.

Allen found no evidence of significant mood or thought disorders despite the fact that al-Jahmi had been confined for psychiatric reasons. He was not taking any psychiatric medications at the time of the evaluation, and it is unclear if he had received psychiatric medication in the past.

“This raises the question of the misuse of medical professionals to confine a patient under the guise of medical treatment, a violation of medical ethics and human rights,” Allen said.

The legal aspects of al-Jahmi’s detention also raise serious concerns, Human Rights Watch and Physicians for Human Rights said. Arrested for a second time in March 2004 for criticizing Libya’s political system and its leader, the Internal Security Agency at first detained al-Jahmi, his wife and eldest son, purportedly for their own protection.

The secret trial began in late 2005, with al-Jahmi apparently charged with trying to overthrow the government, insulting Libyan leader Mu`ammar al-Qadhafi, and contacting foreign authorities. The third charge, al-Jahmi said, resulted from conversations he had with a US diplomat in Tripoli. Al-Jahmi was provided, but rejected, a court-appointed lawyer.

“Fathi al-Jahmi has never used violence or called for the use of violence,” Abrahams said. “He never should have been arrested in the first place. He has suffered four years of detention and health deterioration for speaking about a free press, free elections and nonviolent democratic reform.”

Background

Internal security forces first arrested al-Jahmi, an engineer and former provincial governor, on October 19, 2002, after he criticized the government and Libyan leader Mu`ammar al-Qadhafi, calling for the abolition of al-Qadhafi’s Green Book, free elections in Libya, a free press, and the release of political prisoners. A court sentenced him to five years in prison.

On March 1, 2004, US Senator Joseph Biden met al-Qadhafi in Tripoli and called for al-Jahmi’s release. Nine days later, an appeals court gave al-Jahmi a suspended sentence of one year and ordered his release on March 12.

That same day, al-Jahmi gave an interview to the US-funded al-Hurra television, in which he repeated his call for Libya’s democratization. He gave another interview to the station four days later, in which he called al-Qadhafi a dictator and said, “All that is left for him to do is hand us a prayer carpet and ask us to bow before his picture and worship him.”

Two weeks later, on March 26, 2004, security agents arrested al-Jahmi for a second time, together with his wife and their eldest son. The Internal Security Agency detained them in an undisclosed location for six months, without access to relatives or lawyers. The authorities released al-Jahmi’s son on September 23, 2004, but his wife refused to leave until November 4.

The Internal Security Agency held al-Jahmi at a special facility on the coast near Tripoli. The head of the agency told Human Rights Watch in 2005 that al-Jahmi was being held there for his own protection and because he is “mentally disturbed.”

“I’m responsible for his health care, his detention, and I want to say this: if this man was not detained, because he provoked people, they could have attacked him in his home,” Col. Tohamy Khaled said. “Therefore, he is facing trial. … He’s in special detention because he’s mentally disturbed and we’re worried he will cause a problem for us.”

Physicians for Human Rights visited al-Jahmi in February 2005, and determined that he suffered from diabetes, hypertension and heart disease. The organization called for al-Jahmi’s unconditional release and access to medical care.

Human Rights Watch visited al-Jahmi in May 2005 at the special facility in Tripoli. He said then that he faced charges on three counts under articles 166 and 167 of the penal code: trying to overthrow the government; insulting al-Qadhafi; and contacting foreign authorities. The third charge, he said, resulted from conversations he had with a US diplomat in Tripoli.

Article 166 of the Libyan penal code imposes the death penalty on anyone who talks to or conspires with a foreign official to provoke or contribute to an attack against Libya. Article 167 orders up to life in prison for conspiring with a foreign official to harm Libya’s military, political or diplomatic position.

Al-Jahmi’s continued detention violates both Libyan and international law. The apparent misuse of psychiatry and medical diagnosis to justify detention remains a paramount concern.

Article 31 of Libya’s 1969 Constitutional Proclamation states that detained individuals must be free from “mental or physical harm.” Article 2 of Libya’s Great Green Charter for Human Rights prohibits any punishment that “would violate the dignity and the integrity of a human being.” Both the proclamation and the charter carry constitutional weight.

Libya is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the United Nations Convention Against Torture, and the regional African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. As such, it has multiple, binding legal obligations to ensure that no one is arbitrarily detained or denied basic due process. Persons in detention must not be exposed to inhuman and degrading treatment, but treated “with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person,” including access to necessary health care and medical treatment.

As spelled out in the United Nations Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment, a state’s responsibility to those in their detention includes the provision that “medical care and treatment shall be provided whenever necessary.”

For photos of Fathi al-Jahmi from 2005 and 2008, please contact Ella Moran in New York: morane@hrw.org