(New York) – The trial before Egypt’s state security court of 25 defendants accused of membership in a terrorist organization fails to protect the due process rights of defendants, Human Rights Watch said today. A Human Rights Watch representative monitored the first session of the trial today before the state security court, which the judge adjourned until March 20.

“The government’s reliance on a state security court that lacks fair trial protections means the verdict will be unsound,” said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “If the prosecution feels it has sufficient evidence, it should bring this case before a regular Egyptian criminal court.”

There was a heavy security presence at today’s session, with the result that some families and journalists were denied access to the courtroom. Two mothers of defendants told Human Rights Watch that security officials would only allow one family member per defendant into the courtroom, so they had been unable to see their sons.

The families had only been able to see the defendants during their interrogations before the prosecutor and were not allowed to approach the cage where the defendants are required to sit during the trial. Defense lawyers asked the judge to allow them to meet their clients in private and provide them with 106 pages of prosecutor and police reports they had not been given.

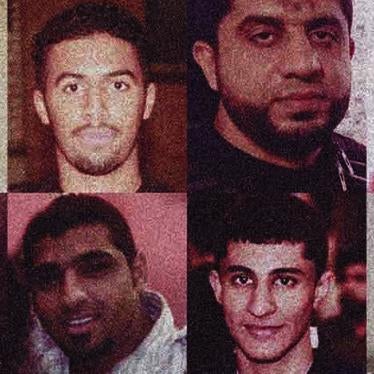

State Security Investigations (SSI) officers arrested 24 of the defendants – 22 Egyptians and two Palestinians – on June 26, July 1, and July 2, 2009. The twenty-fifth defendant is abroad and is being tried in absentia. The ministry of interior announced in a July 9 news release that SSI officers had arrested the 24 men in connection with the armed robbery of a jewelry shop in May 2008 in Cairo’s Zeitoun district and plans to attack Suez Canal shipping. The robbery led to the murder of the shop’s owner, a Coptic Christian, and three employees, prompting the media to call the case the “Zeitoun Cell” trial.

SSI officers detained the men without charge for several weeks, using consecutive 15-day detention orders permitted under the country’s emergency law. The orders, issued by the minister of interior, allow for administrative detention without charge. All were held incommunicado until July 22 and some, such as Mohamed Fahim Hussein, until August 19.

From the time of the arrests, defense lawyers filed a series of complaints before the General Prosecutor to determine where state security officers were detaining the men, to ensure that they had access to a forensic medical doctor, and to seek an order that they be brought before the state security prosecutor and charged immediately. The General Prosecutor opened an investigation into one of these complaints on July 19. The families of the detainees testified about the arrests and their relatives’ inability to locate the men, but the prosecutor did not summon the officers in question and told the lawyers he was unable to determine where the detainees were being held.

In the first session of the trial on February 14, defense lawyers asked the judge to allow them to meet with the defendants in private since they had been unable to do so thus far. One defense lawyer, Ahmed Ezzat, told Human Rights Watch that the first time the detainees’ lawyers were able to make contact with the detainees was when they appeared before the State Security Prosecutor, Hisham Badawy, for interrogation on July 22. Even then, security officers prevented some lawyers from attending the prosecutor’s interrogation of their client. Defense lawyers Khaled Ali and Haitham Mohamedein told Human Rights Watch that the state security prosecutor had interrogated their clients, Mohamed Fahim Hussein and Khaled Abdelhalim respectively, in their absence. Defense lawyers were thereafter able to see the defendants only during subsequent interrogations by the prosecutor and did not otherwise have access to them because security officials did not allow them to visit their clients in detention.

Some of the defendants told the prosecutor that state security forces had tortured them in custody and obtained confessions from them under torture about plans to make weapons to conduct attacks. Mohamed Shabana, another defense lawyer for Mohamed Fahim Hussein, said his client had told the prosecutor that SSI officers had tortured him. Ahmad Adel Hussein, another defendant, told the prosecutor on August 30 that SSI officers had tortured him with electric shocks after his arrest on July 2 and that the torture continued for two weeks. The prosecutor ordered an examination by a forensic medical doctor on September 3, three months after the alleged torture, but the doctor’s report said that he had found no physical traces to prove that torture had taken place.

“There is no justification for failing to provide these men with a fair trial, whatever the charges against them,” Whitson said. “All defendants are entitled to consult with counsel, and all allegations of torture must be investigated in a timely manner.”

Badawy ordered the transfer of the case to the Emergency State Security Court on January 4. He charged all 25 suspects under provisions 86 and 86bis of the penal code with “membership in an illegal organization,” in connection with their alleged affiliation to a group called “El Walaa Wal Baraa” (Loyalty and Innocence), which uses terrorist means to achieve its goals of overthrowing the government, attacking tourists, Copts, and Suez Canal shipping, and illegally possessing weapons. In addition, Badawy charged Mohamed Hussein with establishing and leading the organization, four others with leadership roles in the organization, and the remainder with charges ranging from illegal possession of weapons to illegal entry into and exit from the country via Egypt’s Eastern border.

Human Rights Watch has documented how trials before Emergency State Security courts fail to meet international standards on due process because they do not provide the right to an appeal. Judges in these courts routinely fail to investigate allegations of torture properly, to dismiss confessions obtained under torture, and to allow defendants adequate access to lawyers outside the courtroom. Human Rights Watch monitored the 2006 trial of the men accused of conducting a series of bombings in the Red Sea resort of Taba and concluded that the trial was unfair because of serious allegations of torture and forced confessions, as well as prolonged incommunicado detention and lack of consultation with counsel.

“Governments have a right to protect their citizens from terrorist attacks,” Whitson said. “But real security will not come from a conviction in an unfair trial.”

Egypt’s Emergency Law, under which the 25 men were originally detained, allows for prolonged incommunicado detention, in contravention of international legal standards on the right to a fair trial and to adequate representation by a lawyer. It is during such periods of prolonged incommunicado detention that detainees are at greatest risk of abuse, and it is during this time that three of the defendants in this case alleged having been tortured to force them to confess.

In its report, “Anatomy of a State Security Case,” Human Rights Watch documented the violations that occur in the run-up to a trial before a state security court. One former detainee told Human Rights Watch:

State Security, when they torture you under interrogation, they hint at what your answer should be like. They will throw a headline for a subject to the detainee and then torture him to get the details. Like for example. . . [an SSI officer], he would ask the detainee, the State Security officer would ask: “So what’s the story of the bombings that you were planning to do in this country?” And of course, under torture, the detainee wants this torture to stop, so he wants to say anything that would make this torture stop.

In 2002, The Human Rights Committee, the expert body that monitors compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), expressed concern that Egypt’s “military courts and state security courts have jurisdiction to try civilians accused of terrorism although there are no guarantees of those courts’ independence and their decisions are not subject to appeal before a higher court,” as required by the ICCPR.

In a 2009 report on his visit to Egypt, Martin Scheinin, UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, reiterated “the trial of civilian terrorist suspects in military and Emergency Supreme State Security Courts raises concerns about the impartial and independent administration of justice and furthermore does not comply with the right to have a conviction and sentence fully reviewed by a higher court.” His report will be discussed at the UN Human Rights Council session in March. On February 17, the UN Human Rights Council will review Egypt’s human rights record as part of its Universal Periodic Review of all member countries.

“Governments participating in the review of Egypt’s human rights record should take the Mubarak government to task for its reliance on state security courts,” Whitson said.

Human Rights Watch is also concerned that the charges in the Zeitoun case carry with them a death penalty sentence. Human Rights Watch opposes capital punishment in all circumstances because of its cruel and inhumane nature. International human rights standards stipulate that where the death penalty has not been abolished, it may be imposed only in cases where due process has been scrupulously applied, including the right of the defendant to competent defense counsel, to be presumed innocent until proven guilty, and to appeal both the factual and legal aspects of the case to a higher tribunal.

The defendants in this case are:

1. Mohamed Fahim Hussein

2. Mohamed Khamis Ibrahim

3. Ahmed Saad El Shaarawy

4. Mohamed Salah Abdelfattah

5. Khaled Adel Abdelhalim

6. Ahmad Adel Hussein

7. Yasser Abdel Qader Bassar

8. Ahmad Elsayed El Mansy

9. Farag Radwan El Maany

10. Hani Abdelhayy Abu Muslim (in absentia)

11. Mohamed Ahmad El Dessouky

12. Ahmad Farhan Sayed

13. Ahmad Elsayed Ali

14. Ibrahim Mohamed Taha

15. Mostafa Nasr Mostafa

16. Abdallah Abdelmungid Abdelsamad

17. Ahmad Saad Habib

18. Sameh El Sayed Taha

19. Ahmad Ezzat Noureddin

20. Mohamed Hussein Shouhsa

21. Mohamed Radwan El Maany

22. Tamer Mohamed Abou Gazar (Palestinian national)

23. Mohamed Hassan Abdelmo’ty (Palestinian national)

24. Said Ahmad Mukhaymar

25. Mohamed Ibrahim El Abasiry