Update: On September 13, 2017, the court of First Instance in Ain Tedles, Mostaganem, sentenced Mohamed Fali to a term of six months in prison, suspended, and a fine.

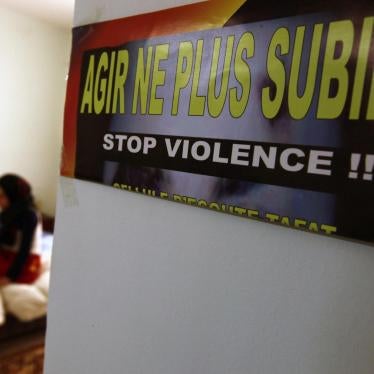

(Beirut) – The arrest of Mohamed Fali, president of Algeria’s Ahmadiyya community on August 28, 2017, is the latest example of a crackdown on the religious minority, Human Rights Watch said today.

Scores of Ahmadis have been prosecuted since June 2016, and some imprisoned for up to six months. Senior government officials have at times claimed that Ahmadis represent a threat to the majority Sunni Muslim faith, and accused them of collusion with foreign powers.

“The persecution of Ahmadis and hateful speech from government ministers shows intolerance for minority faiths, whether they claim to be Muslim or not,” said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “The authorities should immediately release Mohamed Fali and other Algerian Ahmadis and stop attacking this defenseless minority.”

At 9 a.m. on August 28, police came to Fali’s home in Ain Sefra, in the province of Naama, and arrested him on the basis of a 15 February in absentia judgment sentencing him to 3 years in prison.. He is being held in Mostaganem prison.

Founded in India in 1889 by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the Ahmadiyya community identifies itself as Muslim. There are an estimated 2,000 Ahmadis in Algeria, according to the community.

Human Rights Watch interviewed six Ahmadis who faced prosecution around the country, including Fali (before his arrest). Human Rights Watch also reviewed the case files in three trials.

Fali told Human Rights Watch that the prosecutions started in June 2016 in the Blida governorate, and spread to other areas. A year later, some 266 Ahmadis had faced charges around the country, Fali said. Human Rights Watch could not independently confirm this figure.

Authorities charged them under one or more of the following charges, Fali said: denigrating the dogma or precepts of Islam; participation in an unauthorized association; collecting donations without a license; and possession and distribution of documents from foreign sources that endanger national security. At least 20 have faced a charge of practicing religion in an unauthorized place of worship under Algeria’s 2006 law governing non-Muslim religions, Fali told Human Rights Watch, even though Ahmadis consider themselves Muslim.

Fali said that convictions and sentences were issued in 123 cases, and have ranged from three months to four years in prison. There were four acquittals. The remaining 161 prosecutions are still in the investigative phase. Fali said 36 persons spent time behind bars, with the longest to date being six months.

Several Ahmadis have faced two or more trials, sometimes in different parts of the country. For example, Fali faces charges in six cases and is either under investigation or on trial in Blida, Chlef, Mostaganem, Boufarik, and Sétif. He spent three months in Chlef prison in provisional detention from February to May. Another Ahmadi, who did not want to be identified, said he was prosecuted in three different trials in Blida, Boufarik, and Chlef.

Fali told Human Rights Watch that the courts had placed under judicial control at least 70 Ahmadis facing prosecution. This required the defendants to sign in on a regular basis with the court.

Authorities have also denied Ahmadis the right to form an association, using broad language in the Associations Law that they had previously used to restrict the right of other Algerian groups to form associations. They demolished a building in Larbaa, in the province of Blida, that Ahmadis were intending to use as a place of worship and as the headquarters for their association, on the pretext that it was an “unauthorized place of worship.”

Several Ahmadis told Human Rights Watch that authorities confiscate religious books, documents about the Ahmadiyya faith, computers, identity cards, and passports during searches. One Ahmadi said that they confiscated his university diplomas and never returned them.

Ahmadi representatives told Human Rights Watch that at least 17 Ahmadis were suspended from their public-sector jobs. Human Rights Watch reviewed five of these suspensions; in each case, the only grounds provided were the ongoing prosecutions and court cases against the individual.

Under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Algeria ratified, governments must ensure the right to freedom of religion, thought, and conscience of everyone under their jurisdiction, and in particular religious minorities. This right includes the freedom to exercise the religion or belief of one’s choice publicly or privately, alone or with others. Algeria’s constitution guarantees freedom of religion but states that “this freedom must be exercised in respect of the law.”

Hateful Speech

Government ministers have made several anti-Ahmadi comments. In October 2016, the Minister of Religious Affairs Mohamed Aissa described the Ahmadi presence in Algeria as part of a “deliberate sectarian invasion” and declared that the government brought criminal charges against Ahmadis to “stop deviation from religious precepts.” In February, he stated that Ahmadis are damaging the very basis of Islam.

In an interview in April 2017, Aissa seemed to have tempered his position. He said that the Algerian state does not intend to fight the Ahmadiyya sect. However, on July 5, he reiterated his belief that Ahmadis are manipulated by “a foreign hand” aiming to destabilize the country, and accused their leaders of collusion with Israel.

In April, Ahmed Ouyahia, then chief of cabinet to President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, said that “there are no human rights or freedom of religion” in the matter of the Ahmadis, because “Algeria has been a Muslim country for 14 centuries.” He called on Algerians to “protect the country from the Shia and Ahmadiyya sects.”

Denial of the Right to Form an Association

On November 15, 2015, a group of Ahmadis held a constitutive general assembly to create a new association they called the “Ahmed al-Khair Association” (Ahmed Charity), whose objective, according to bylaws Human Rights Watch has reviewed, is to perform charity projects and to help poor and marginalized communities. On March 26, 2016, they submitted the founding documents to the Ministry of Interior to register the association, as required by the 2012 Associations Law. On May 26, they received a letter from the ministry notifying them of the refusal to register the association.

According to the ministry’s reply, which Human Rights Watch has reviewed, the refusal is based mainly on articles 2 and 27 of the Associations Law. Article 2 gives the authorities broad leeway to refuse authorization if they deem the content and objectives of a group’s activities to violate Algeria’s “‘fundamental principles’ (constantes nationales) and values, public order, public morals, and the applicable laws and regulations.” Article 27 lists all the necessary papers and required documents that the association must provide to the ministry to be legally registered.

Interference with Faith During Trials

Authorities prosecuted the 266 Ahmadis under one or more charges: denigrating the dogma or precepts of Islam, punishable by a prison term of three to five years and a fine of up to 100,000 Algerian dinars (US$908), under article 144 of the penal code; participation in an unauthorized association, under article 46 of the Associations Law, punishable by a prison sentence of three to six months and a fine of 100,000 to 300,000 dinars; collecting donations without a license, under articles 1 and 8 of the decree 03-77 of 1977 regulating donations; conducting worship in unauthorized places, under articles 7, 12, and 13 of Ordinance 06-03 Establishing the Conditions and Rules for the Exercise of non-Muslim Religions; and possession and distribution of documents from foreign sources threatening national security, under article 96-2 of the penal code, punishable by up to three years in prison.

Several Ahmadis and their lawyers told Human Rights Watch that prosecutors and trial judges asked defendants intrusive and offensive questions about their religious practice. For example, Salah Dabouz, a lawyer defending many of the prosecuted Ahmadis, said that in a hearing on June 21 before the Batna appeals court, the prosecutor asked defendants: “Why do you profess allegiance to a Hindu and not to the Prophet of Islam? Why do you pray alone and not in a Mosque as other Muslims do?”

Mohamed Fali said that the judge in his trial in the first instance court in Chlef, on May 22, 2017, asked him: “Do you believe that Muhammad is the last of the prophets? Why don’t you pray at the Friday prayer at the mosque?”

The judges’ reasoning in several convictions of Ahmadis, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, demonstrates that the trials are based on religious arguments.

For example, the written judgment against six Ahmadis at the first instance court of Batna, dated March 27, 2017, states that the gendarmerie, while monitoring the activities of the religious groups in its region, received information about the existence of a group of people belonging to the Ahmadiyya faith. They searched their houses and seized all their books, computers, and other documents related to the “offense.” When the gendarmerie interrogated them, they admitted belonging to the Ahmadiyya community and exercising their faith in private settings. They also provided information on why and when they joined the faith. The judgment cites as its basis for the guilty verdict these statements attributed to the six defendants by the police.

The written judgment includes quotes from the representative of the Ministry of Religious Affairs who said that the ministry decided to join the case as a civil party (partie civile) because the Ahmadis were disseminating “ideas that are foreign to Algerian society that could have a dangerous impact on the beliefs of the society and its stability.”

To justify a guilty finding on the charge of distributing foreign material harmful to national security, the court cites only the seizing of books printed in Great Britain and documents printed from an Ahmadiyya website. It states, “[t]hese books and publications contain ideas that are alien to the national religious framework and this leads necessarily to harming the national interest.” The court defines national interest as being “the economic, military, cultural, or religious principles of the state,” and finds that Ahmadiyya doctrine challenges the national religious identity, which is based on the Malekite rite of Islam.

Based on this reasoning, the court convicted the accused of denigrating the dogma or precepts of Islam, participation in an unauthorized association, collecting donations without a license, possession and distribution of documents from foreign sources threatening national security, and sentenced them to four years in prison and a 300,000 dinar fine. It did not retain the charge of practicing religious rites in unauthorized places, stating that Ordinance 06-03 applies only to non-Muslims whereas Ahmadis claim to be Muslims. The defendants have filed an appeal against this verdict, Dabouz, their lawyer, said.

Human Rights Watch reviewed two other judgments, one issued by the first instance court in Chlef on May 22, 2017, the second by the first instance court in Blida on January 31, 2017. In both judgments, the courts refer to the circumstances of the arrest, stating that gendarmerie started an investigation after receiving information that the Ahmadis were threatening “the appearance of the religion” and “undermining Islam.”

Cases

Mohamed Fali, president of the Jamaa Islamia Ahmadia in Algeria (The Islamic Ahmadiyya community), 44, tradesman, lives in Bousmail, Tipaza

Fali told Human Rights Watch that he has faced six distinct trials since June 2016. On June 2, 2016, gendarmes and municipal authorities came to demolish the building the Ahmadis were constructing in Larbaa, Blida province, for meetings and prayers. The same day, around 20 gendarmes came to arrest Fali and search his home. They confiscated his computer and books about the Ahmadiyya faith. He stayed five days in the gendarmerie detention center, where he was interrogated, before the first instance court in Blida provisionally released him.

The prosecutor charged Fali with participation in an unauthorized association, collecting donations without a license, and possession and distribution of documents from foreign sources threatening national security. On January 31, Fali, who had eight co-defendants in this case, was convicted in absentia while he was detained in another case, and received a six-month sentence and a 200,000 dinar fine. Fali presented himself to the court in Blida to oppose his conviction in this case. His retrial is scheduled to open on September 19.

Fali’s second prosecution was in Chlef, where he was provisionally detained for three months between February and May 2017. He received a suspended sentence on May 22 to one year in prison and a 500,000 dinar fine for the same offenses as in the Blida case, in addition to the charge of denigrating the dogma or precepts of Islam. While he was in Chlef prison, he was sentenced in absentia in Mostaganem to three years in prison and a 50.000 dinar fine (USD$449), on February 15, for the same charges as in the Chlef and Blida cases. He appealed his sentence and is awaiting his appeal trial. He was also sentenced to a 100,000 dinar fine in another trial in Boufarik, on January 30, and has two other cases in the investigative phase, in Sétif and in Boufarik. In the second case in Boufarik, the investigative judge put him under judicial control, requiring that he register every Wednesday at the courthouse.

He said for each of these investigations the gendarmerie searched his house, confiscated his computers and telephones, arrested and detained him for several days, and interrogated him about his religion, his ties with the Ahmadiyya international movement, and his motivations.

On August 28, authorities arrested Fali after a search-and-seizure operation at his house. His lawyer, Dabouz, said that the arrest is linked to his trial in absentia at the Mostaganem court, and that his retrial in this case is scheduled for September 6. He is currently in pretrial detention at the Mostaganem prison.

S.B., 37, doctor, from Tipaza

S.B., who did not want to be named, said that he has faced three trials since 2016. He was part of the group arrested on June 2, 2016, in Larbaa, Blida province, where a court sentenced him to six months in prison in absentia while he was detained for another case, and a 200,000 dinar fine on charges of participating in an unauthorized association; collecting donations without a license; and possessing and distributing documents from foreign sources threatening national security. S.B. presented himself to the court to oppose his conviction in absentia. His retrial is scheduled to open on September 19, 2017.

The second trial of S.B. took place on January 30, in Boufarik, where he received a 100,000 dinar fine on the same charges. The third was in Chlef, for which he spent three months in provisional detention and received a one-year suspended sentence on May 22. He also said that the Chlef hospital suspended him from his post as a doctor. Human Rights Watch reviewed the decision by Chlef hospital, dated February 22, 2017 and signed by the director, which cites the prosecution of S.B. as a basis for the measure and the temporary suspension of his salary.

Z.M., 29, Salesman, from Chraga

Z.M., who asked not to be named for fear of retaliation, said he used to work as a salesman in his father’s shop. Gendarmes came to his house on October 5, 2016, seized books, printed material, and the founding documents of the Ahmadiyya charity association Ahmad al-Khair, and arrested him for interrogation. He spent one night in detention. Gendarmes transferred him the next day to the prosecutor’s office, who indicted him on the charge of “belonging to an unauthorized association” and “possession of foreign documents threatening state security.” The first instance court in Douera sentenced him to 18 months in prison, suspended, and a 100,000 dinar fine. He said the appeals court confirmed the lower court’s decision. He said during the appeals hearing, the trial judge asked him, “Are you aware of the Koranic verse that says, ‘Those who change their faith should be killed?’”

B.S.H., 24, University Student, from a City Southwest of Algiers

B.S.H., who also asked not to be named for fear of retaliation, said he was first prosecuted in June 2016 with eight other Ahmadis. The gendarmerie arrested him in Larbaa on June 2, 2016, after authorities destroyed the Ahmadi house of worship under construction. Provisionally released after the gendarmerie interrogated him, B.S.H. was tried and sentenced in absentia by the first instance court in Blida to six months in prison and a 200,000 dinar fine on charges of participating in an unauthorized association; collecting donations without a license; and possessing and distributing documents from foreign sources threatening national security. Like his co-defendants Fali and S.B., he opposed his conviction and is scheduled to have a new trial on September 19.

On March 1, gendarmes arrested him again and searched his house, seizing his computer and cell phone. The investigative judge in the first instance tribunal ordered his provisional detention for three and a half months. A court sentenced him to a 50,000 dinar fine on June 18, on the charge of participation in an unauthorized association, and released him from prison.

H.I., 29, student in Chraga

H.I. told Human Rights Watch that he was prosecuted and sentenced twice on charges of belonging to an unauthorized association, possession and distribution of foreign documents threatening state security, and collecting donations without a license. The first prosecution was before a Tipaza court, which sentenced him on December 28 to 18 months in prison, suspended, and a 100,000 dinar fine. The appeals court confirmed the sentence on April 2.

At H.I.’s second trial, the first instance court in Chlef sentenced him on May 22 to three months in prison, suspended, and a 50,000 dinar fine. He has appealed the verdict, he said.

In the Chlef judgment, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, the judges ruled that the mere possession of books on the Ahmadiyya faith, which gendarmes seized from H.I.’s home, was sufficient proof that he was engaged in a “proselytizing enterprise that could destroy the unity of society and threaten public order, since the Islamic religion is a pillar of the national identity and is enshrined in the Constitution.”

Algerian Legislation and International Standards on Freedom of Religion

Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) guarantees individuals the right to hold and to display their religious beliefs. It states:

Everyone shall have the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion. This right shall include freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice, and freedom, either individually or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching. No one shall be subject to coercion which would impair his freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice.

The UN Human Rights Committee’s General Comment No. 22 to Article 18 specifies that freedom of thought, including freedom of conscience and religious conviction, is a right that cannot be limited.

Article 27 of the ICCPR states, “In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with the other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practice their own religion, or to use their own language.”

The committee, in its General Comment No. 22, expressed concern with “any tendency to discriminate against any religion or belief for any reason, including the fact that they are newly established, or represent religious minorities that may be the subject of hostility on the part of a predominant religious community.”

The Algerian constitution provides for religious freedom, but states that “exercise of this freedom must be done in respect of the law.” The main law governing the practice of non-Muslim religions, Ordinance 06-03 of February 28, 2006, restricts the religious freedom of, and discriminates against, non-Muslims, by imposing restrictive regulations on worships from which Muslims are exempt. Collective worship can take place only in a building designated for that purpose and with prior permission from the National Commission for the Practice of Religions. Collective worship can be organized only by religious organizations that have been established according to the law.

Under Ordinance 06-03, proselytizing by non-Muslims is a criminal offense and carries a maximum punishment of one million dinars ($12,845) and five years’ imprisonment for anyone who “incites, constrains, or utilizes means of seduction tending to convert a Muslim to another religion; or by using to this end establishments of teaching, education, health, social, culture, training…or any financial means.” Authorities used the Ordinance 06-03 to prosecute four Protestant Christians in August 2008, and courts sentenced them to two to three months in prison, suspended. Ordinance 06-03, by imposing blanket prohibitions on proselytizing, which apply only to non-Muslims, violates the right of individuals under the ICCPR to the “freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice.” According to the UN Committee, freedom of religion includes “the freedom to prepare and distribute religious texts or publications,” and “the right to replace one’s current religion or belief with another.”

The Algerian penal code also criminalizes “offending the Prophet Muhammad” and denigrating the creed or prophets of Islam. Authorities used these provisions on September 6, 2016 to convict and sentence Slimane Bouhafs, a Christian convert, to three years in prison. He is still serving time in Belair prison in Sétif province.