(New York) – United Nations member countries should not vote for China and Saudi Arabia, two of the world’s most abusive governments, for seats on the UN Human Rights Council, Human Rights Watch said today. Russia’s numerous war crimes in Syria’s armed conflict makes it another highly problematic candidate.

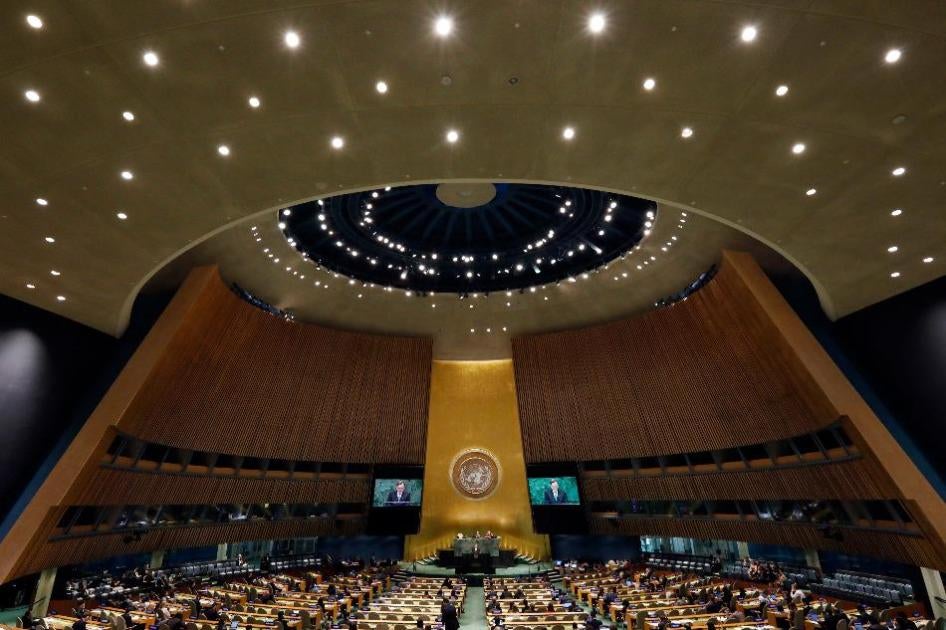

On October 13, 2020, the UN General Assembly will hold elections for 15 seats on the 47-nation Human Rights Council for three-year terms beginning on January 1, 2021. So far, only the Asia-Pacific regional group has a competitive slate, with five countries running for four seats. This means that the other candidate countries, even those not qualified, are virtually assured of seats on the UN’s top human rights body.

“Serial rights abusers should not be rewarded with seats on the Human Rights Council,” said Louis Charbonneau, UN director at Human Rights Watch. “China and Saudi Arabia have not only committed massive rights violations at home, but they have tried to undermine the international human rights system they’re demanding to be a part of.”

UN General Assembly Resolution 60/251, which created the Human Rights Council, urges states voting for members to “take into account the contribution of candidates to the promotion and protection of human rights.” Council members are required to “uphold the highest standards in the promotion and protection of human rights” at home and abroad and “fully cooperate with the Council.”

Alongside Saudi Arabia and China, Nepal, Pakistan, and Uzbekistan are also vying for the four seats available to the Asia and Pacific group. Four countries have announced candidacies for the four Africa seats: Ivory Coast, Malawi, Gabon and Senegal. In addition to Russia, Ukraine is seeking one of two Eastern European seats. In the Latin American and Caribbean group, Mexico, Cuba, and Bolivia are running unopposed for three seats. Britain and France are seeking the two seats available to the Western European and others group.

“Uncompetitive UN votes like this one make a mockery of the word ‘election,’” Charbonneau said. “Regional slates should be competitive so states have a choice. When there’s no choice, countries should refuse to vote for unfit candidates.”

On June 26, an unprecedented 50 UN experts called for “decisive measures to protect fundamental freedoms in China.” They warned about China’s mass human rights violations in Hong Kong, Tibet, and Xinjiang, the suppression of information at the outset of the Covid-19 pandemic, and attacks on rights defenders, journalists, lawyers, and critics of the government across the country. Over 400 civil society organizations from more than 60 countries echoed this call in a global appeal. On October 6, 39 states echoed those calls in a joint statement at the UN that voiced deep concern about Chinese government abuses. Human Rights Watch has also documented China’s systematic attempts to undermine UN human rights mechanisms.

Saudi Arabia, despite announced reform plans, continues to target human rights defenders and dissidents, including women’s rights activists and others it has arbitrarily detained and prosecuted. There has been little accountability for past abuses, including the brutal killing of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi, or implementation of any meaningful reforms. Thirty-three countries at the current Human Rights Council session denounced Saudi rights violations and called for the release of all those arbitrarily detained. And the Saudi-led coalition continues to commit war crimes against civilians in Yemen.

Saudi Arabia and China have a history of using their seats on the Human Rights Council to prevent scrutiny of their abuses and those by their allies. Saudi Arabia has threatened to withdraw millions of dollars in UN funding to stay off the secretary-general’s annual “list of shame” for violations against children. China has repeatedly acted to prevent the participation of rights defenders at the UN.

Russia for years has actively participated in joint military operations with the Syrian government that have deliberately or indiscriminately killed civilians and destroyed hospitals and other protected civilian infrastructure in violation of international humanitarian law. Russia, often backed by China, has used its veto power in the UN Security Council 16 times to enable Syria to continue using chemical weapons with impunity and to block referral of the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court.

Most recently, Russian vetoes ended humanitarian aid delivery to many thousands of Syrians in need of food and medicine in non-government-held areas, undermining the ability of local authorities to combat the spread of Covid-19

Another government that has used its past stints on the council to undermine human rights is Cuba’s. Havana worked hard to protect abusive governments like Nicolás Maduro’s in Venezuela from Human Rights Council scrutiny. At home, the Cuban government suppresses and punishes all forms of dissent and routinely targets journalists, protesters, and human rights defenders.

“It’s not good for human rights or for the rights council when the worst rights violators get elected,” Charbonneau said. “Fortunately, even the most abusive governments have been unable to stop the council from shining a light on rights violations around the world, though not for lack of trying. That’s grounds for hope.”

Correction: In a previous version of this release we stated that Russia has used its veto power in the UN Security Council 15 times to enable Syria to continue using chemical weapons with impunity and to block referral of the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court. It has been updated to reflect that Russia has used the veto power 16 times.