With the G7 Summit around the corner and debates about waiving intellectual property rules for Covid-19 vaccines and other health products heating up, all eyes will be on Chancellor Angela Merkel. Merkel has stood in the way of the waiver, making it harder for the world’s poor to swiftly get vaccines, treatments, and testing kits.

Over 100 low-and-middle-income governments back a proposal before the World Trade Organization to temporarily waive some rules in the Agreement on Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement). The proposal, if adopted, would waive complex rules that are barriers to speeding up and geographically diversifying the production of lifesaving Covid-19 vaccines and other health products.

Waiving these rules would enable governments to collaborate swiftly, creating regional manufacturing hubs around the world through technology transfers. These hubs could churn out health products faster to ebb the surging pandemic.

Protecting the intellectual property of pharmaceutical giants, as the EU is doing, leaves dozens of other industries hostage. The garment industry is a key example.

Technology transfers in the pharmaceutical industry are not unprecedented. The World Health Organization implemented a technology transfer program for influenza vaccines, a model that can be adapted for Covid-19 vaccines. With political will and co-operation by pharmaceutical companies, many existing factories could be repurposed to manufacture vaccines in less than six months. A TRIPS waiver can hasten the process and dismantle export barriers.

The US and New Zealand have signaled support for negotiations on the proposal. But Merkel – as well as the European Commission – are still blocking it. They are recycling old approaches focused on industry-led and industry-controlled partnerships, while a deadly status quo persists.

The European Commission touts its vaccine donations. While welcome, their donations are nowhere near the number of doses the world needs. It disingenuously repeats rosy and debunked projections of vaccine production even as companies struggle with supply delays and production challenges.

The Commission cites its monetary donations to a global vaccine procurement facility, called COVAX, to justify opposition to the TRIPS waiver. But these donations don’t substitute for support for the waiver. Money does not ease the barrage of complex global rules that delay expanding manufacturing. Nor does it magically manifest more vaccines. COVAX itself is grappling with supply shortages. The vaccines COVAX has supplied to date are barely enough to cover 1 percent of the more than 100 countries relying on them.

The EU argues that lifting its export restrictions will help. But there aren’t enough vaccines to export.

Finally, the Commission claims voluntary licensing by pharmaceutical companies will help the scarcity of medical products, though these are slow and restrictive. It hasn’t backed or gotten big pharmaceutical companies to cooperate, though, with two voluntary licensing initiatives—Covid-19 Technology Access Pool and the WHO Covid-19 mRNA Technology Transfer Hub—that are gathering dust. Meanwhile, numerous manufacturers from various countries report that they’re waiting to get licenses.

With each day’s delay, the death count mounts, and devastating disparities in global vaccine equity persist. Large parts of the world, especially African countries, don’t have enough doses to vaccinate even 2 percent of their populations.

Over the nearly eight months that the proposal has been stalled, the number of deaths has more than trebled, to over 3.5 million. The International Chamber of Commerce estimates that the current approach could cost the global economy US$11.7 trillion, half of which would be borne by advanced economies even after they vaccinated their own populations.

As for the damage to other industries by a delay, take the garment industry, in which the German government has invested resources and efforts to improve workers’ rights through the German Partnership on Sustainable Textiles. While not radical in its reform agenda, the partnership has facilitated important conversations on workers’ rights among German apparel and footwear brands, inching towards better work.

The garment industry has been ravaged by pandemic surges. According to the partnership, many German retailers and fashion brands with “brick and mortar” shops have lost significant business, closed stores, and are struggling with furloughs. Esprit, Takko, and Adler have filed for bankruptcy.

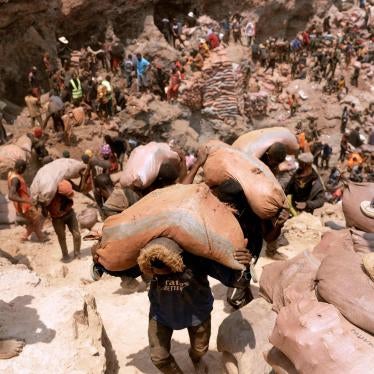

Garment factories have closed or laid off workers, putting them out of jobs and food on their plates. Estimates for global unpaid wages and severance for workers range from $13 million to $850 million with #PayUp campaigns to ensure workers at least get paid for products they’ve already made. And decisions stalling the waiver proposal continue to affect the rest of the world. In a recent statement, the Clean Clothes Campaign network highlighted outbreaks of Covid-19 in a garment factory in Sri Lanka, which infected an estimated 10,000 people in the local community.

So while Merkel and the European Commission work to protect garment workers from fires and building collapses, they are blocking measures that could save the industry and workers from Covid-19 deaths, illness, and debt.

Whether Merkel pushes the European Commission to vote in favour of the TRIPS waiver proposal and commits to technology transfers will be an acid test for Germany and EU’s commitment to rights. The world’s workers are waiting, hoping.

Aruna Kashyap is senior counsel for business and human rights and Wenzel Michalski is Germany director at Human Rights Watch.