(Washington, DC) – Members of the Colombian National Police have committed egregious abuses against mostly peaceful demonstrators in protests that began in April 2021, Human Rights Watch said today. Colombia’s government should take urgent measures to protect human rights, initiate a comprehensive police reform effort to ensure that officers respect the right of peaceful assembly, and bring those responsible for abuses to justice.

On April 28, thousands of people took to the streets in dozens of cities across Colombia to protest proposed tax changes. The government withdrew the proposal days later, but demonstrations about a range of issues – including economic inequality, police violence, unemployment, and poor public services – have continued. Police officers have responded by repeatedly and arbitrarily dispersing peaceful demonstrations and using excessive, often brutal, force, including live ammunition. Human Rights Watch has documented multiple killings by police, as well as beatings, sexual abuse, and arbitrary detention of demonstrators and bystanders.

“These brutal abuses are not isolated incidents by rogue officers, but rather the result of systemic shortcomings of the Colombian police,” said José Miguel Vivanco, Americas director at Human Rights Watch. “Comprehensive reform that clearly separates the police from the military and ensures adequate oversight and accountability is needed to ensure that these violations don’t occur again.”

While the protests have been mostly peaceful, some individuals have committed grave acts of violence in the context of the protests, including burning police stations and attacking police officers, two of whom died.

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 150 people, most by phone, including victims, their relatives and lawyers, witnesses, justice sector officials, officials of the human rights Ombudsperson’s Office, and human rights defenders, in 25 cities across Colombia. Human Rights Watch also met with Colombia’s vice president, who is also the foreign minister; the police chief; the attorney general; and the head of the Military Justice System.

Members of the Independent Forensic Expert Group (IFEG) of the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT), an international group of prominent forensic experts, provided expert opinion on some evidence of abuses. Human Rights Watch also reviewed police and medical records, necropsy reports and photos of the victims, publications by local rights groups, and media reports. Human Rights Watch also corroborated more than 50 videos posted on social media and obtained information about the government’s response to past police abuses from the Ombudsperson’s Office, the Inspector General’s Office, and the Defense and Interior Ministries.

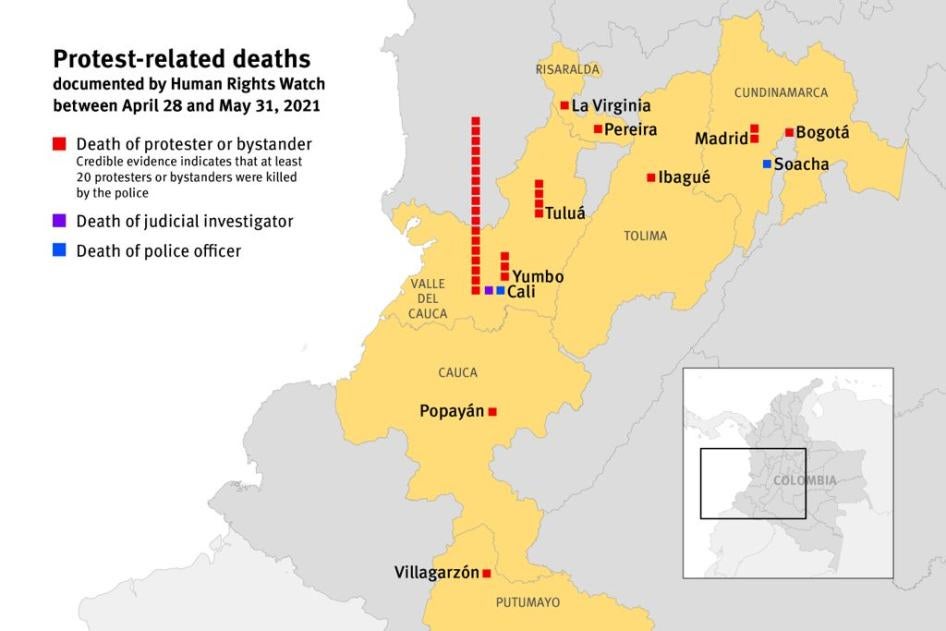

Human Rights Watch has received credible reports of 68 deaths occurring since the protests began. Human Rights Watch received reports of these deaths through local groups, including Temblores and Defender la Libertad, a coalition of rights groups documenting police violence, and independently documented each case with direct evidence.

So far, Human Rights Watch has confirmed that 34 deaths occurred in the context of the protests, including those of 2 police officers, 1 criminal investigator, and 31 demonstrators or bystanders, at least 20 of whom appear to have been killed by the police. Armed people in civilian clothes have attacked protesters, killing at least five.

Colombian authorities should carry out prompt and independent investigations into all cases of police abuse and other serious acts of violence, including by armed people in civilian clothes who have attacked protesters, Human Rights Watch said. They should also investigate any officers who may have failed to protect demonstrators from attacks by others.

Credible evidence indicates that the police killed at least 16 protesters or bystanders with live ammunition fired from firearms, Human Rights Watch found. The vast majority of them had injuries in vital organs, such as the thorax and head, which justice sector officials said are consistent with being caused with the intent to kill.

At least one other victim died from beatings and three others from inappropriate or excessive use of teargas or flash bang cartridges.

Over 1,100 protesters and bystanders have been injured since April 28, according to the Ministry of Defense, though the total number is most likely higher as many cases have not been reported to authorities. Human Rights Watch documented nine cases of severe eye injuries, including seven with likely permanent loss of vision in one eye, apparently from teargas cartridges, stun grenades, or kinetic impact projectiles fired from riot guns.

Victims injured include journalists and human rights defenders who were covering the protests, including many who wore vests identifying them as such.

On June 3, the Ministry of Defense said that, since April 28, police officers had detained over 1,200 people for crimes allegedly committed during the protests. Prosecutors had only charged 215. Hundreds were released after a judge or prosecutor concluded that there was no evidence linking them to a crime, or that their due process rights were violated during detention, the Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch.

In addition, the police took into custody over 5,500 people using a legal provision that allows police officers to “transfer” a person to an “assistance or protection center” to “protect” them or others. Human Rights Watch documented multiple cases of arbitrary detention, including by misusing the “protection” provision.

On May 14, the Ombudsperson’s Office reported 2 cases of rape, 14 cases of sexual assault, and 71 other cases of gender-based violence by police officers, including slapping and verbal abuse. Colombian rights groups have reported additional cases. Human Rights Watch documented two cases of sexual violence by police officers against protesters.

Human Rights Watch also documented 17 beatings, often with police truncheons. One victim, Elvis Vivas, 24, died in a hospital after a brutal beating by police officers.

At least 419 people have been reported missing since the protests began. On June 4, the Attorney General’s Office said that it had found 304 of them. In some cases, the people who reported them missing were not aware that they had been detained.

While most demonstrations were peaceful, some individuals engaged in serious acts of violence, including attacking police officers and police stations with rocks and Molotov cocktails, looting, and burning public and private property. As of June 2, over 1,200 officers had been injured, at least 192 severely, 2 officers had died and 7 officers remained hospitalized, according to the Defense Ministry. Twenty police officers had been injured by firearms, the police chief said. On April 29, several people beat up and sexually abused a woman police officer as they attacked a police station in Cali.

Some protesters blocked roads for prolonged periods, at times limiting or impeding the distribution of food or the circulation of ambulances, particularly in the states of Valle del Cauca and Cundinamarca. These limitations have at times undermined access to health supplies, including oxygen for patients with Covid-19, the Health Ministry said. A newborn baby girl died on May 23 after protesters blocked the ambulance that was carrying her between Cali and Buenaventura.

“Violence against police officers and road blocking that impedes access to food or health services are unjustifiable, but they are no excuse for police brutality,” Vivanco said.

Incidents of abuse by the police in 2019 and 2020 prompted calls for comprehensive police reform, including from Human Rights Watch.

The Colombian police force is under the authority of the Defense Ministry and has been deployed to fight armed groups alongside the armed forces, in a manner that has often blurred their distinct functions. In situations involving armed conflict, the use of force is governed by international humanitarian law, and the rules are very different than in a civilian context, such as in protests. Police officers implicated in abuses are also often tried in military courts, where there is little chance of accountability.

Colombia needs a civilian force that is trained to respond to protests in a manner respectful of human rights, and whose members are held accountable for abuses, Human Rights Watch said. Establishing a clear separation between the police and the military is a key first step.

On June 6, President Iván Duque announced that his government would take steps to “transform” the police. Some of the initiatives, such as a proposed reform of the police’s disciplinary system, could have a positive impact on police abuses if properly designed and implemented, Human Rights Watch said. But other proposals seem cosmetic, and, overall, the changes announced fall short of the reforms needed to prevent human rights violations and hold those responsible to account.

President Duque has acknowledged that the police committed some abuses and said officers involved would be prosecuted and punished. But Duque has rejected other major proposals for police reforms, claiming that his government has “zero tolerance” toward abuse.

Yet the police’s internal disciplinary system, which lacks necessary independence, has failed to hold officers responsible for abuses in protests in 2019 and 2020, data obtained by Human Rights Watch shows. The Attorney General’s Office, which conducts criminal investigations, has also failed to achieve meaningful progress in investigations into abuses committed during those protests.

For detailed recommendations and further information on Human Rights Watch’s findings, please see below.

Arbitrary Dispersal of Peaceful Protests; Excessive Use of Force

The Colombian government deployed regular police officers and members of the police anti-riots squadron (ESMAD) to respond to the protests. The regular officers attend a 45-hour course on responding to peaceful demonstrations every two years, but do not receive anti-riot training, the police chief told Human Rights Watch.

Additionally, since May 1, President Duque has deployed the army to “assist” the police, though not to use force against protesters. On May 28, Duque increased the number of deployed soldiers, and ordered several governors and mayors to work with security forces to “adopt the necessary measures” to disperse “blockades.”

Under international human rights law, the authorities should protect peaceful assemblies and should not disperse them even if they consider them unlawful. They should avoid using force unless necessary and proportionate to respond to specific incidents of violence. Peaceful protests that block traffic may be dispersed, as a general rule, only if they cause serious and sustained disruptions.

However, Human Rights Watch has documented repeated instances in which the ESMAD or police violated these principles, arbitrarily dispersing peaceful protests, or using indiscriminate and excessive force, including firearms.

Unlawful Use of Lethal Weapons

Under international human rights standards, firearms may only be used when strictly necessary to address an imminent risk to life or physical integrity. The use of firearms to disperse an assembly is always unlawful.

Under Colombian law, police can use lethal weapons to defend themselves or others “when there is imminent threat of death or serious injury, or to prevent a particularly serious crime that involves a serious threat to life.”

The Colombian police chief told Human Rights Watch that police, including regular officers and members of the anti-riots squadron (ESMAD), have not used lethal weapons during the demonstrations.

However, Human Rights Watch corroborated several videos showing police officers shooting in the context of the demonstrations, in circumstances in which there appeared to be no risk to life or physical integrity.

Human Rights Watch documented 16 cases in which the police appear to have killed unarmed protesters or bystanders with live ammunition. In at least 15 of those cases, the victims had gunshot wounds in vital organs: 7 were shot in the thorax, 6 in the head, and 2 in the abdomen. Those injuries are consistent with an intent to kill, justice sector authorities told Human Rights Watch.

Indiscriminate and Improper Use of Less Lethal Weapons

Police repeatedly used teargas against peaceful protesters, demonstrators and officials of the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office said.

It appears that police deployed teargas from riot guns in a reckless and dangerous manner on multiple occasions. Police should fire teargas cartridges toward the sky, to slow down the heavy projectile’s trajectory in a downward arc to land on the ground. However, interviews with multiple protesters and human rights officials and videos corroborate that police officers shot the cartridges straight into the crowd.

The Colombian police also used a launching system, known as Venom, to shoot up to 30 teargas, smoke or flash bang cartridges at a time. Human Rights Watch corroborated videos of its use in several cities, including Bogotá and Popayán (Cauca state). The system is supposed to shoot projectiles in a “parabolic” trajectory – that is, toward the sky – to avoid “direct impact” against protesters, police told Human Rights Watch in a letter. But the letter also says it shoots from an angle as small as 10 degrees, which would not make it “parabolic.”

Human Rights Watch corroborated videos of police shooting the Venom from the ground straight toward demonstrators in Popayán.

This launching system has wide-area indiscriminate effects and cannot be used in a way that distinguishes any legitimate threats, Human Rights Watch said. Its usage is inappropriate for peaceful protests. Even if isolated events of violence occur in the context of protests, police need to respond in a proportionate, not indiscriminate, manner.

Human Rights Watch documented cases of five people apparently injured by the impacts of teargas cartridges and three killed, including:

In 2019, Colombian police fired pellets using 12-gauge pellet shotguns against protesters, killing one protester. In January 2020, the Inspector General’s Office, an independent body, found that police officers had limited, if any, training on how to use the weapon. In September 2020, the Supreme Court suspended the use of those weapons by police.

The police chief told Human Rights Watch that police are not currently using any kind of pellet shotguns. He said the 12-gauge pellet shotguns remain stored in police stations.

The police said they are using riot guns to fire cartridges containing 12 or 24 balls that they said are made of plastic. Human Rights Watch documented several cases in which protesters appear to have been injured by these kinetic impact projectiles.

Some were hit by multiple projectiles at the same time, suggesting they were shot at close range, given that these projectiles scatter over a distance.

Beatings

Human Rights Watch documented 17 cases of protesters or bystanders being beaten, often with police truncheons. Some were later detained. One died due to the injuries.

Gender-Based Violence

On May 14, the Ombudsperson’s Office reported 2 cases of rape, 14 cases of sexual assault, and 71 other cases of gender-based violence by police officers, including slappings and verbal abuse. Colombian rights groups have reported additional cases. Human Rights Watch documented two cases of sexual violence by police officers against protesters:

Arbitrary Detention; Disproportionate Charges

Hundreds of protesters were detained by police and released after a judge or prosecutor concluded that there was no evidence linking them to a crime, or that their due process rights had been violated during detention, the Attorney General’s Office said. Human Rights Watch documented in detail 27 cases of people who appear to have been arbitrarily detained. Prosecutors, human rights officials, and victims’ lawyers reported scores of additional cases.

Prosecutors have also filed disproportionate charges of “terrorism” against some demonstrators who allegedly engaged in vandalism. While the penalty for destruction of property is between 16 and 90 months, the penalty for terrorism is up to 22 years-and-a-half in prison. International human rights standards require that criminal charges and penalties be proportionate to the gravity of the conduct at issue and the culpability of the alleged offender. Authorities should not arbitrarily use “terrorism” charges to address lower-level offenses, Human Rights Watch said.

The police also took into custody over 5,500 people using a legal provision that allows police officers to “transfer” a person to an “assistance or protection center” for their own “protection” or that of others. Human Rights Watch documented several cases in which police officers appear to have misused this provision.

The law allows for such “transfer” only when it is the “only means available to prevent a risk to life or physical integrity” and requires first contacting relatives of the person to see if the person can be transferred to their care; if the relatives cannot assume their care, police are to take them to an “assistance center,” health center, hospital, or other location specifically designated for such transfers by the municipal government, or to their homes if possible.

The law says that people may not under any circumstances be transferred to detention centers. In the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the police took people to police stations instead of to health centers or administrative detention sites and police did not call their relatives first, as required under Colombian law.

Police detained José Mauricio García Nieto, 24; Dan Brayer Andrade Bolaños, 22; José Mario Ramírez Álzate, 22; Daniel Navarrete Varón, 22; Jorge Andrés Noguera Flórez, 23; and Santiago Ramírez Duque, 26; in the afternoon of May 25 in Tuluá, Valle del Cauca. The police report said that at the time of their arrest, four of them were throwing rocks at buildings, one was lighting a plastic bottle to supposedly throw it at a police station, and the sixth was “inciting” people to “oppose a police operation.”

At an online hearing before a judge next day, whose video recording Human Rights Watch reviewed, the prosecutor charged the six individuals arrested in Tuluá with “terrorism.” The only evidence he presented was the police report and statements by police. The prosecutor acknowledged that the specific acts allegedly committed could amount only to a crime of destruction of property, but said the “terrorism” charge was justified because the detainees were part of a “mob” that “agitated” them. The prosecutor did not present any evidence that they were acting in coordination with each other or with other protesters, and acknowledged that they were not involved in the burning of the Tuluá courthouse, which happened that night. Colombian law does not allow pretrial detention of defendants charged with destruction of property, a minor crime, but it does for terrorism.

The prosecutor also said at the hearing the detainees had told him through WhatsApp calls that the police had beaten them. However, the detainees were not taken to see a medical examiner to document the injuries, a separate police report reviewed by Human Rights Watch shows, allegedly due to the unrest in the city. Without presenting any evidence, the prosecutor said that there was a “possibility” that they had resisted arrest and that it was “possible” that the use of force by the police was appropriate. The judged agreed – and ruled that the arrest was legal.

On May 28, the same judge ruled that the detainees were a “threat to the community” and ordered that they be held in pretrial detention. The six young men remain imprisoned in jail in Popayán, their lawyers and relatives told Human Rights Watch.

Alleged Participation of Armed Groups and Civilians

The Colombian government said that several armed groups, including the National Liberation Army (ELN) and groups that emerged from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), had “infiltrated” the protests to commit vandalism and attack the police. The Attorney General told Human Rights Watch on June 4 that the authorities arrested 11 alleged members of armed groups in connection with violence during demonstrations.

Separately, armed people in civilian clothes have engaged in violence against protesters. In Pereira, Risaralda state, a group of people in civilian clothes appeared when Lucas Villa, a protester and social leader, was delivering a speech against the government during a protest on May 5. One of them shot and killed him, a witness who was also severely wounded told Human Rights Watch. Justice sector officials familiar with the case said that the evidence indicates local drug trafficking groups may be responsible.

In some cases, police officers failed to respond when people in civilian clothes engaged in violence against protesters. Human Rights Watch corroborated videos showing armed men firing at protesters while standing next to police officers in Cali on May 28. The police did not appear to take action to prevent or stop the attacks. The next day, a police commander acknowledged that the agents had “failed to comply with their duty” and said they would be investigated.

The director general of the Police, General Jorge Luis Vargas, said that no plainclothes police officers had been deployed for crowd control operations or to arrest protesters. However, Human Rights Watch corroborated videos showing that police officers in civilian clothes arrested protesters who were blocking a highway in Cali on May 17.

Limited Accountability for Police Abuses

Colombian authorities, including the Attorney General’s Office, which conducts criminal investigations, and the police and the Inspector General’s Office, which can carry out disciplinary proceedings, have made limited progress in investigating police abuse against protesters.

The Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch on June 4 that it had charged only one police officer in connection with abuses committed during the recent wave of protests. He was charged on May 13 for the homicide of a protester, Marcelo Agredo Inchima. The Attorney General’s Office’s Unit of Citizen Security, which is conducting all the investigations into police abuses, said it had appointed additional prosecutors and investigators to handle these cases and that the head of the unit was conducting weekly meetings with prosecutors to assess progress in each case.

The director of the Military Justice System told Human Rights Watch on May 28 that military judges had opened 34 investigations in connection with the protests, including for 10 killings and 11 cases of injuries. Under regional human rights norms, grave human rights violations should not be tried before military courts.

The police chief said on May 31 that the police had opened disciplinary investigations into 170 officers for possible misconduct during the current wave of protests. Of those, three are under disciplinary investigation for homicide and have been temporarily suspended, two have been suspended for other alleged infractions, and the rest continue their regular work. The Inspector General’s Office, which also conducts disciplinary investigations, said on May 31 that it had opened 78 investigations into possible abuses of power and excessive use of force by police officers; the vast majority remained in preliminary stages.

Progress in investigating police abuses in previous protests has also been lacking. On June 4, the Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch that it had opened 90 investigations into police abuses during the 2019 protests and other 116 during the 2020 protests. The office said a trial had started in five of the 2020 cases and that it had brought charges in two others. No officer has been charged in connection with abuses committed during the 2019 protests.

The Inspector General’s Office has also failed to achieve meaningful progress. On May 10, the office told Human Rights Watch that it had opened 24 investigations of police abuses during the 2019 protests and another five during the 2020 protests. No officer had been disciplined and most cases remained in preliminary stages.

On April 17, 2021, the Defense Ministry told Human Rights Watch that police had opened 40 disciplinary investigations in connection with the 2019 protests. Of those, 24 had been closed without any officer being disciplined, the ministry said, while the others were pending. The ministry said that 54 of the 92 disciplinary investigations the police had opened in connection with the 2020 protests had been closed, in most cases because the investigators could not identify the police officer involved. Only two officers had been disciplined in cases that appeared connected to human rights violations and four others had been acquitted.

The police disciplinary system lacks independence, Human Rights Watch found. There is no separate career for disciplinary investigators, the police chief said. This means that there are no safeguards to ensure that investigators do not end up working alongside, or under the command of officers they previously investigated. Colombian law also allows the police chief to revoke any disciplinary decision.

The police chief asserted that the disciplinary system is overwhelmed with proceedings for minor issues, which he said slow down the progress of investigations into serious offenses. He said he is working on a reform to improve the handling of the most serious offenses and transfer cases concerning “serious human rights violations” to the Inspector General’s Office, an independent body.

Possible Contempt of Supreme Court Ruling

In September 2020, the Supreme Court ordered several police reforms to prevent abuses during protests. Yet Human Rights Watch found that efforts to comply with the court’s ruling have been mostly pro forma and have had little impact on police actions. The main exception is the Supreme Court’s ban of the 12-gauge shotgun, a weapon which, to Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, police have not used during the current wave of protests.

The Supreme Court ordered the Colombian government to establish a new protocol on the “use of force during peaceful demonstrations.” The government did publish a new protocol in January 2021, but it does not include any new measures or oversight mechanisms to prevent excessive use of force during protests and ensure accountability when it occurs.

The court also ordered that human rights groups and UN organizations be allowed to “verify” detentions and “protection” transfers during protests. In October 2020, after that year’s protests, the Inspector General’s Office and the police created a committee for that purpose including the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) but excluding local human rights groups. Human Rights Watch learned that the police and the Inspector General’s Office have in many cases failed to convene the committee during the recent protests.

The court also mandated the government to order, by October 2020, all executive branch officials to protect and respect all “non-violent protests,” including anti-government ones. The government has failed to do so.

The court also ordered the Ombudsperson’s Office to closely monitor ESMAD abuses against protesters. Officials of the Ombudsperson’s Office have been monitoring the response to the protests and seeking dialogue with protesters to end road blocking. But the limited staff devoted to the protests has struggled to keep up and the Ombudsperson has failed to periodically report on and unequivocally condemn police abuses.

On May 27, the Supreme Court initiated a formal review to determine whether the government had failed to comply with its ruling.

Recommendations

To the administration of President Iván Duque, including the national police chief:

- Take immediate steps to end human rights abuses in the context of protests and begin to repair the harm done, including by:

- Unequivocally condemning human rights violations, including instances of excessive use of force and sexual violence by police, as well as cases in which police agents failed to stop attacks committed by armed people in plainclothes.

- Apologizing, on behalf of the Colombian state, for police abuses committed during the protests.

- Ensuring that all government officials refrain from using language that may be perceived as stigmatizing protesters.

- Ensuring that the police, including the ESMAD, protect and do not disperse peaceful protests and pursuing approaches that do not involve use of force in any efforts to end instances of streets blockings.

- Prioritizing disciplinary investigations into police abuses committed at least since the 2019 protests and committing to report periodically on progress in these investigations. The police should hold accountable through disciplinary investigations police officers who committed abuses during the protests and unit and operation commanders who may have ordered abuses, or who may bear responsibility under Colombian law for failing to take appropriate steps to prevent crimes or hold those responsible to account. They should also investigate any officers who may have failed to protect demonstrators from attacks by others.

- Banning the use of kinetic impact projectiles and the Venom launching system, pending an independent assessment of the danger they pose, of the protocols for their use, and of the training provided to officers.

- Conduct a thorough review of police crowd control protocols, practices, and equipment, as well as of police training on the use of force, to ensure respect for the right of peaceful assembly and other human rights.

- Provide reparations, as well as health services, to victims of police violence, including post-rape care and comprehensive services for victims of sexual violence.

- Convene the committee created to oversee detentions and “protection transfers” during demonstrations, and reform the protocol that created the committee to ensure participation of civil society representatives in it.

- Significantly expand crowd-control training for police officers, including for those who are not part of ESMAD.

- Strengthen systems to prevent and punish gender-based violence by police officers.

To the Colombian Congress:

- Initiate a process with meaningful participation by civil society groups and international human rights agencies operating in Colombia to reform Colombia’s National Police including by:

- Transferring the police from the Defense Ministry to the Interior Ministry or to a new Ministry of Security to ensure that the police are clearly separated from the military.

- Establishing strong safeguards to ensure that “protection transfers” are not used arbitrarily.

- Reforming the police’s disciplinary system to ensure its independence.

- Ensuring that the military justice system does not handle investigations into human rights violations committed by police officers.

- Reviewing police protocols on the use of force to ensure strong mechanisms are put in place to prevent excessive use of force by police officers.

- Ensuring strong independent oversight and control over police officers.

- Strengthening mechanisms to prevent and punish gender-based violence by police officers.

- Reform the Criminal Code to ensure that prosecutors are required to investigate ex officio any injuries, including those caused by police officers, regardless of whether they have received a criminal complaint.

To the Attorney General’s Office:

- Prioritize criminal investigations into police abuses, including by investigating officers directly involved in abuses committed in the context of protests at least since 2019, as well as unit commanders and police commanders in charge of operations who may have ordered abuses, or who may bear responsibility under Colombian law for failing to take appropriate steps to prevent crimes or hold those responsible to account.

- Create a special group of prosecutors and investigators within the Unit of Citizen Security exclusively charged with investigating police abuses against protesters committed at least since 2019.

- File lawsuits asking judges to rule that the Attorney General’s Office—not the military justice system—should handle cases of human rights violations.

- Investigate ex officio any cases where judges have ruled that police officers have violated detainees’ due process rights in ways that may amount to a crime under Colombian law.

To the Inspector General’s Office:

- Ensure disciplinary accountability for police abuses, including by investigating officers directly involved in abuses committed in the context of protests at least since 2019, as well as unit commanders and police commanders in charge of operations who may have ordered abuses, or who may bear responsibility under Colombian law for failing to take appropriate steps to prevent crimes or hold those responsible to account.

- Support lawsuits that seek to transfer cases of human rights violations from the military justice system to regular prosecutors and courts.

- Convene the committee created to oversee detentions and “protection transfers” during demonstrations, and reform the protocol that created the committee to ensure participation of civil society representatives in it.

- Investigate ex officio any cases where judges rule that police officers have violated detainees’ due process rights in ways that may amount to a disciplinary infraction under Colombian law.

To the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office:

- Closely monitor abuses by the ESMAD during protests, as ordered by the Supreme Court in the September 2020 ruling.

- Increase the number of officials involved in monitoring police abuses during protests and ensure that they receive protection and adequate support to conduct their work.

- Report publicly and periodically on cases of police abuses documented during the protests.