(New York) – The Cambodian government’s broad political crackdown in 2017 effectively extinguished the country’s flickering democratic system at the expense of basic rights, Human Rights Watch said today in its World Report 2018.

In the 643-page World Report, its 28th edition, Human Rights Watch reviews human rights practices in more than 90 countries. In his introductory essay, Executive Director Kenneth Roth writes that political leaders willing to stand up for human rights principles showed that it is possible to limit authoritarian populist agendas. When combined with mobilized publics and effective multilateral actors, these leaders demonstrated that the rise of anti-rights governments is not inevitable.

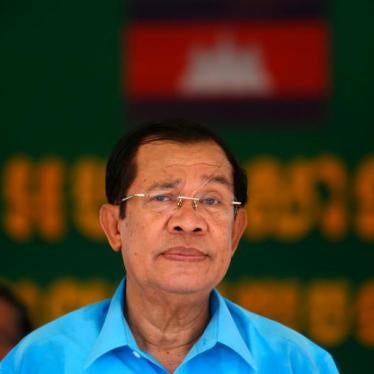

The government, which has been dominated by Prime Minister Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) for more than three decades, detained the political opposition’s leader on dubious treason charges, dissolved the country’s main opposition party, and banned more than 100 opposition party members from political activity. Authorities also increasingly misused the justice system to prosecute political opponents and human rights activists, and forced several independent media outlets to close.

“The last vestiges of democratic government in Cambodia disappeared in 2017,” said Brad Adams, Asia director. “Hun Sen cemented his 33-year rule into dictatorship at the expense of the Cambodian people’s basic rights.”

Hun Sen, who controls the country’s security services and courts, expanded his campaign of arbitrary arrests and summary trials against political opponents and activists. Throughout 2017, authorities suppressed protests and banned gatherings and processions. Several nongovernmental organizations were also threatened with closure or were closed. At year’s end, approximately 20 political prisoners remained in detention.

Hun Sen’s actions against Cambodia’s opposition appeared to be motivated by fear that the CPP would lose national elections scheduled for July 29, 2018. The opposition made large electoral gains during the 2013 national elections and the 2017 commune elections.

Throughout 2017, the government used increasingly threatening political rhetoric. Hun Sen and other leaders repeated claims that any election victory by the opposition would lead to “civil war,” and threatened to use violence against those who “protest” or seek a “color revolution,” a term authorities use to portray peaceful dissent as an attempted overthrow of the state.

In May, Hun Sen stated he would be “willing to eliminate 100 to 200 people” to protect “national security,” and suggested opposition members “prepare their coffins.” In November, he said he regretted not massacring protesters.

In September, authorities arrested and detained Kem Sokha, president of the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), on charges of treason. His predecessor, Sam Rainsy, had years earlier been forced into exile by spurious criminal cases. On November 16, the government-controlled Supreme Court dissolved the CNRP and imposed political bans of five years on 118 of its members.

“With the main opposition party dissolved, there’s no chance of holding genuine democratic elections in July 2018,” Adams said. “That seems to be the point of Hun Sen’s crackdown: elections as a charade.”

The crackdown also targeted media outlets. In September, authorities forced the independent Cambodia Daily newspaper to close on the pretext of an unpaid tax bill, and brought tax-related charges against its owners. Two of its reporters were also investigated on baseless “incitement” charges.

The government in August revoked radio licenses for stations broadcasting Voice of America and Radio Free Asia (RFA), forcing RFA’s Cambodian bureau to close, and closing the independent radio station Voice of Democracy. Authorities charged two RFA journalists with espionage in November for allegedly providing information to RFA.

Cambodia’s sharply deteriorating political situation comes after decades of international assistance in support of the 1991 Paris Agreements, which committed Cambodia to international human rights standards and a democratic multiparty political system.

“The international effort set in motion by the 1991 Paris Agreements has essentially failed,” Adams said. “Concerned countries need to impose travel bans, targeted sanctions, and other punitive measures on the Cambodian leadership if there is any hope of restoring the democratic promise of 1991.”