Introduction

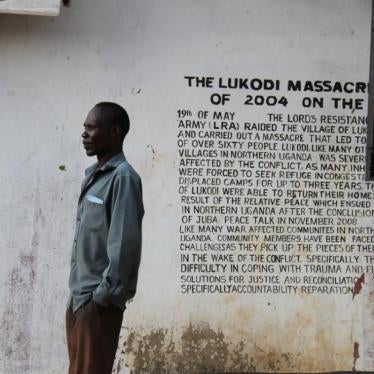

Under Article 53 of the Rome Statute, the prosecutor has important responsibility to decide "whether to initiate an investigation," and, upon investigation, to decide "that there is not a sufficient basis for a prosecution." In making these decisions, the Rome Statute states that a factor to be considered by the prosecutor is "the interests of justice." The prosecutor's decision regarding the "interests of justice," however, is subject to review by the Pre-Trial Chamber. Because the phrase "interests of justice" is not precisely defined, Human Rights Watch believes it is important that the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) establish guidelines as to how the phrase should be construed. Such guidelines are important in order that the International Criminal Court (ICC) be perceived as a judicial institution that operates on the bases of transparency and principles. The need for clarity regarding the phrase has already taken on importance regarding the situation in Northern Uganda, where community leaders argue that the ICC's continued investigation may have the potential to jeopardize peace talks, and where the prosecutor has suggested that he could suspend the investigation, invoking the concept of "the interests of justice."

On November 30 and December 1, 2004, the OTP held a biannual consultation with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) during which it circulated a "Consultation Proposal on the Interests of Justice." In that document, the OTP solicited comments by NGOs regarding the meaning of the phrase "in the interests of justice" in the Rome Statute. It is with that purpose that Human Rights Watch submits this policy paper. This paper also addresses draft regulations by the OTP pertaining to the "interests of justice," on which the prosecutor has also solicited comments.

Part I addresses the phrase "in the interests of justice" in context, and concludes that the construction most consistent with the object and purpose of the Rome Statute and its context would be a narrow one. Specifically, the prosecutor may not fail to initiate an investigation or decide not to go from investigation to trial because of developments at the national level such as truth commissions, national amnesties, or the implementation of traditional reconciliation methods, or because of concerns regarding an ongoing peace process, because that would be contrary to the object and purpose of the Rome Statute.

Part II considers the requirements of international law to prosecute the most serious crimes, and similarly concludes that a construction of the phrase that would be consistent with those requirements would be a narrow one.

Part III discusses what would be sound policy for the OTP regarding the phrase "interests of justice." Over several decades the international human rights movement has confronted the seemingly conflicting objectives of justice and peace. That experience indicates that justice, rather than being an obstacle, is a precondition for meaningful peace. A broad interpretation, for example, one that is influenced by the existence of peace negotiations and gives weight to the impact of an investigation upon such negotiations could leave the OTP hostage to political controversies and subject to manipulation by warring parties or factions.

Part IV considers the factors that the OTP should consider when examining the "interests of justice," and how those factors should be interpreted. Finally, Part V addresses issues regarding the OTP's discretion over timing of an investigation, and finds that such discretion does exist to some extent. We conclude by making specific recommendations on revising the OTP's current draft regulations on "the interests of justice" and the importance of publishing future regulations construing that phrase.

The OTP Should Adopt A Narrow Construction of The Words "Interests Of Justice"

Under Article 53(1) and (2) of the ICC Statute the Pre-Trial Chamber of the ICC will ultimately decide whether a prosecutorial decision to proceed with or cease an investigation is "in the interests of justice." The Pre-Trial Chamber will review the prosecutor's decisions regarding "the interests of justice."[1] HRW believes the OTP should adopt a strict construction of the term "interests of justice" in order to adhere to the context of the Rome Statute, its object and purpose, and to the requirements of international law.[2] Human Rights Watch also believes that a strict construction by the OTP would be sound for policy reasons.

Background

The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (Vienna Convention) provides that a treaty shall be interpreted according to: (1) "the ordinary meaning to be given to . . . terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of [the treaty's] object and purpose"; and (2) "any relevant rules of international law applicable . . . ."[3] Similarly, Article 21 of the Rome Statute provides that, in making legal determinations, the Court shall apply: "In the first place, [its] Statute, Elements of Crimes and its Rules of Procedure and Evidence; (b) in the second place, where appropriate, applicable treaties and the principles and rules of international law . . . ."[4]

Thus, in considering the meaning of the phrase "in the interests of justice" in Article 53, it is necessary to consider the ordinary meaning of the phrase in its context, and the object and purpose of the Rome Statute. The "ordinary meaning" of the phrase is not clear from the text of Article 53 viewed in isolation. If, however, the phrase is construed in the context of the Rome Statute, including the preamble and Article 16 (which permits the U.N. Security Council to defer an ICC investigation or prosecution for twelve months based on considerations of international peace and security), it is clear that there are limits to the discretion permitted to the OTP by that phrase.

A. The text of Article 53

Article 53(1) of the Rome Statute requires the prosecutor, in deciding whether to initiate an investigation, to consider, among other things, whether "[t]aking into account the gravity of the crime and the interests of victims, there are nonetheless substantial reasons to believe that an investigation would not serve the interests of justice. . . ."[5] Similarly, Article 53(2) allows the prosecutor to conclude that there "is not a sufficient basis for a prosecution" if, among other things a "prosecution is not in the interests of justice, taking into account all the circumstances, including the gravity of the crime, the interests of victims and the age or infirmity of the alleged perpetrator, and his or her role in the alleged crime . . . . "[6]

Thus, the prosecutor has the discretion (subject to Pre-Trial Chamber review) to determine not to initiate an investigation or not to proceed to trial based on "the interests of justice." The question, of course, is how broad that discretion should be, and whether there are limits to it.

B. No definitional agreement reached at Rome

There has been intense debate about the meaning of the phrase "in the interests of justice" in Article 53. It is fairly clear that no consensus as to the meaning of the phrase "the interests of justice" was agreed upon at the Rome Conference.[7] For example, neither the language of the Rome Statute nor actual language in the travaux préparatoires reflect any agreement that the phrase "the interests of justice" permits the prosecutor to consider the existence of a national amnesty or truth commission process, or ongoing peace negotiations as factors to be evaluated.[8] There was, however, agreement at Rome on one aspect of Article 53. Namely, there is a procedural check when the prosecutor acts solely based on "the interests of justice"-review by the Pre-Trial Chamber as to any such determinations.[9]

I. A Narrow Reading Of Article 53 Would Be Consistent With The Object And Purpose Of The Rome Statute

Human Rights Watch believes that the construction of the phrase "in the interests of justice" that would be consistent with the object and purpose of the Rome Statute as shown in the preamble would be a narrow one. Specifically, the prosecutor may not fail to initiate an investigation or decide not to proceed with the investigation because of national efforts, such as truth commissions, national amnesties, or traditional reconciliation methods, or because of concerns regarding an ongoing peace process, since that would be contrary to the object and purpose of the Rome Statute. As discussed below, there is some flexibility that the prosecutor has in terms of the timing of an investigation. (See Part V, below.)

Moreover, the Rome Statute explicitly addresses the issue of when an investigation or prosecution may not be in conformity with the aims of Chapter VII of the U.N. Charter (for example, where there is a tension or conflict between the work of the Court and international peace and security). Article 16 provides that the United Nations Security Council, acting under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, may take action to defer an investigation or prosecution for a 12-month period.[10] Clearly, in those circumstances, it is the Security Council, not the prosecutor, who is empowered to act, taking into account issues such as international peace and security.

A. The Preamble

The plain meaning of Article 53 must be considered in its context.[11] The Vienna Convention provides that "[t]he context for the purpose of the interpretation of a treaty" includes "its preamble and annexes."[12]

The Rome Statute's preamble makes clear that the Statute was established in response to massive atrocities that threaten the peace, security and well-being of the world.[13] It goes on to reject impunity for serious crimes and emphasizes in unequivocal terms that serious crimes must be prosecuted and punished:

Affirming that the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole must not go unpunished . . .

Determined to put an end to impunity for the perpetrators of these crimes and thus to contribute to the prevention of such crimes,

Recalling that it is the duty of every State to exercise its criminal jurisdiction over those responsible for international crimes, . . .

Determined . . . to establish an independent permanent International Criminal Court . . . with jurisdiction over the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole, . . .

Resolved to guarantee lasting respect for and the enforcement of international justice . . . . [14]

Thus, the preamble to the Rome Statute makes it clear that the Statute's purpose is to prosecute the most serious crimes of concern to the international community. Contributing to the prevention of "crimes under international criminal law is the main purpose and the mission of the court, in order to guarantee ‘lasting respect for the enforcement of international justice.'"[15] "From the words of the Preamble of the Statute, it seems that the goal of putting an end to the impunity of the perpetrators of [genocide, aggression, crimes against humanity and systematic or large-scale war crimes] is the main reason for the creation of the ICC."[16] Thus, if the phrase "in the interests of justice" is construed in light of the object and purpose of the Rome Statute, a construction that permits consideration of a domestic amnesty, domestic truth commission or peace process and results in permanently not initiating an investigation or proceeding from investigation to trial would be in principle at odds with the object and purpose of the Rome Statute, as set forth in its preamble.[17]

Other articles in the Rome Statute that use the phrase "interests of justice" also suggest that the phrase really means "so that justice may be administered in an orderly way" or the "good administration of justice," and not any broader notion. For example, Article 55(2)(c) of the Rome Statute uses the term in relation to the provision of legal assistance by the court: legal assistance must be provided "where the interests of justice so require."[18] The phrase also appears in Articles 61, 65, and 67 of the treaty. In all four of these provisions, the phrase is always used in a way that suggests that the "good administration of justice" or "advancing the trial process" and not any broader meaning is intended.[19] The use of the phrase in the ICC's Rules of Procedure and Evidence similarly suggests such an interpretation.[20]

B. Article 16

The Rome Statute addresses the interface of international peace and security and justice. It allocates decision-making to the Security Council as to when an investigation should be halted because it may interfere with international peace and security.

Article 16 provides that:

No investigation or prosecution may be commenced or proceeded with under this Statute for a period of 12 months after the Security Council, in a resolution adopted under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations, has requested the Court to that effect; that request may be renewed by the Council under the same conditions.[21]

There is no such power allocated to the prosecutor, nor any suggestion that he should be involved in such political determinations. The prosecutor of the ICC is a "judicial, non-political organ, with no political legitimation and liability. . . ."[22] The Rome Statute specifies that the prosecutor "shall act independently" and that no member of his Office shall "seek or act on instructions from any external source."[23] Because his work, however, might "have an extremely strong political impact . . . the need was perceived, by the Diplomatic Conference, to avoid undesirable political consequences - affecting international peace and security - which might be produced by the activity of such a non-political organ."[24]

The Security Council's deferral power was put in place as a mechanism to deal with situations where international peace and justice seem to be in conflict and thus the requirement that the deferral only be allowed pursuant to a Chapter VII resolution.[25] Thus, Article 16 is "the vehicle for resolving conflicts between the requirements of peace and justice where the Council assesses that the peace efforts need to be given priority over international criminal justice."[26] "The Security Council's deferral power confirms its decisive role in dealing with situations where the requirements of peace and justice seem to be in conflict."[27] Thus, authorities on the subject explain that formal deferral is only appropriate where "there is a good reason to believe that a specific investigation carried out by the prosecutor might provoke such a grave political crisis as to endanger international peace and security."[28] While Article 16 does not address implications on internal peace and security of an ICC investigation, war crimes of the scope addressed in Article 8 of the ICC Statute[29] as well as crimes against humanity are often likely to affect international peace and security.

Thus, the only means by which the Rome Statute explicitly permits concerns about a peace process to "trump" prosecutorial efforts is through a deferral by the U.N. Security Council acting under its Chapter VII powers. While Human Rights Watch has concerns about how Article 16 may be applied-namely, the danger of political interference in the judicial process[30]-the Rome Statute clearly allocates the authority in this regard to the Security Council.[31] Allowing the prosecutor to make prosecutorial decisions based on political factors of the same nature as those conceived of in Article 16 would undermine the perception and reality of the prosecutor as independent and beyond political influence.[32]

Accordingly, under the Rome Statute scheme: (1) the only construction of "interests of justice" that would be consistent with the preamble of the Rome Statute would be a narrow one that does not permit considerations of domestic amnesties, truth processes, traditional mechanisms or peace negotiations; and (2) the Rome Statute allocates political decision-making regarding the impact of an investigation on international peace and security to the U.N. Security Council, not the prosecutor.

II. The Requirements of International Law Lead to A Narrow Construction Of The Words "In The Interests Of Justice"

The Vienna Convention additionally requires consideration of relevant rules of international law,[33] as does the Rome Statute.[34] Because international law mandates that the most serious crimes be subject to prosecution, it would be contrary to international law to construe "the interests of justice" as allowing the worst perpetrators to avoid prosecution due to a national peace process, truth commission proceedings or amnesty. Accordingly, Article 53 also must be narrowly construed in order to adopt a construction that is consistent with international law.

A. Under international law, there is an obligation to prosecute serious international crimes

As a matter of both international law and the Rome Statute, there is a duty to prosecute serious international crimes pursuant to customary international law and jus cogens.

Various commentators agree that the duty to prosecute serious international crimes is required pursuant to customary international law and jus cogens. "The widespread use of the formula ‘prosecute or extradite' either specifically stated, explicitly stated in a duty to extradite, or implicit in the duty to prosecute or criminalize, and the number of signatories to . . . numerous conventions, attests to the existing general jus cogens principle."[35] "Obligations erga omnes ‘flow from a class of norms the performance of which is owed to the international community as a whole.'"[36] The norms of jus cogens and obligations erga omnes require states to punish perpetrators of crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes.[37] The obligation to "extradite or prosecute" (aut dedere aut judicare), also referred to as universal jurisdiction, can be found in approximately seventy international criminal law conventions.[38]

One commentator insists that "there exists little doubt" that the obligation to prosecute or extradite in cases of genocide or crimes against humanity "falls within customary international law."[39] Another argues:

Today it is generally recognized that customary international law of a peremptory nature places an obligation on each nation-state to search for and bring into custody and to initiate prosecution of or to extradite all persons within its territory or control who are reasonably accused of having committed, for example, war crimes, genocide, breaches of neutrality and other crimes against peace.[40]

Thus, jurisdiction over the crimes covered by the Rome Statute "has achieved the status of customary international law, for neither the international community nor any state nor group of states can validly negate the criminal responsibility of any individual who has committed international crimes."[41] The obligation to prosecute genocide derives from obligations under the Genocide Convention;[42] the obligation to prosecute at least "grave breaches" derives from the Geneva Conventions;[43] and the obligation to prosecute crimes against humanity arguably derives from customary international law.[44]

Regarding governments that have ratified the Rome Statute, this obligation to prosecute the most serious crimes also arguably is recognized in the Rome Statute itself. The obligation to prosecute is clearly expressed, for example, in the preamble:

Affirming that the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole must not go unpunished and that their effective prosecution must be ensured by taking measures at the national level and by enhancing international cooperation. . . .

Recalling that it is the duty of every State to exercise its criminal jurisdiction over those responsible for international crimes, . . . .[45]

This obligation to prosecute can also be seen in Article 17 of the Rome Statute:

[T]he duty to prosecute crimes against humanity is an integral component of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC). As contemplated by the Rome Statute within the principle of complementarity, national courts have not only the first right to prosecute human rights violations, but an obligation to prosecute them. In particular, regarding Article 17 of the statute, ‘the point to be emphasized is that the competence to bring the perpetrator(s) of crimes within the jurisdiction of the ICC to justice remains the prime responsibility of national States.' As a result, provided that the alleged human rights violator is not surrendered to the ICC, a duty exists for states subject to the jurisdiction of the ICC to prosecute them in domestic courts.[46]

Accordingly, as to the perpetrators of the worst crimes, international law does not permit their exemption from prosecution. The deference that the Rome Statute gives to the tension between peace and justice is, as discussed above, through a Security Council deferral under Article 16.

B. As a matter of international law, the most serious crimes should not be the subject of an amnesty

The trend in international law is that state amnesty provisions must be considered void if they attempt to amnesty the most serious crimes. As the Sierra Leone Special Court recently held:

Where jurisdiction is universal, a State cannot deprive another State of its jurisdiction to prosecute the offender by the grant of amnesty. It is for this reason unrealistic to regard as universally effective the grant of amnesty by a State in regard to grave international crimes in which there exists universal jurisdiction. A State cannot bring into oblivion and forgetfulness a crime, such as a crime against international law, which other States are entitled to keep alive and remember.[47]

This principle that one state cannot amnesty a crime other states are entitled to "keep alive" should apply all the more to states that are parties to the Rome Statute.

The United Nations has also repeatedly reflected this position against amnesties regarding the most serious crimes. For example, regarding the 1999 Lomé Peace Accord, despite the opposition of Sierra Leone President Kabbah, the U.N. Special Representative attached a reservation to the Lomé Peace Agreement stating: "The United Nations holds the understanding that the amnesty provisions of the Agreement shall not apply to international crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and other serious violations of international humanitarian law."[48] The Secretary-General also issued a statement that addressed the terms of the Lomé Peace Agreement: "Some of the terms under which this peace has been obtained, in particular the provisions on amnesty, are difficult to reconcile with the goal of ending the culture of impunity. . . ."[49] Thus, the United Nations did not accept amnesty provisions for the worst crimes and the Secretary-General instructed his Special Representative to enter a reservation to that effect.[50]

Numerous additional documents and bodies also highlight the developing legal trend opposing amnesty for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and other violations of international humanitarian law.[51]

State practice in recent years has also supported the trend in international law rejecting amnesties for the most serious human rights abuses. Taking seriously their duty to prosecute the perpetrators of the most serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law, a number of countries in Latin America, including, Argentina, have recently moved to repeal long-standing blanket amnesties. In Africa, peace accords signed by all fighting parties in the DRC and Burundi have expressly excluded amnesty for genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity (although the Burundian parliament later passed a law granting "provisional amnesty"). The amnesty law passed by the Ivorian parliament in August 2003 excluded from its scope those responsible for serious human rights crimes. These developments in the law show that states are tending to limit the reach of amnesties. By contrast the issuance by governments of blanket amnesties often indicates an unwillingness by such governments to deal with the worst crimes.

Accordingly, as shown in parts IIA&B above, truth commissions, amnesties or traditional justice processes, regarding the types of crimes covered by the Rome Statute, should not be regarded as alternatives to international prosecution and the trend is that they contravene international law. It is also clear that to terminate permanently an investigation due to concerns with its impact on peace and stability would contravene the obligation to prosecute the most serious crimes. Thus, the existence of a domestic amnesty, truth commission process or peace negotiations should not result in a determination not to proceed under Article 53. The logical construction of Article 53 that is consistent with both the object and purpose of the Rome Statute and the requirements of international law is a narrow one.

III. Policy Reasons Also Suggest That The OTP Should Adopt A Narrow Reading Of The Phrase "Interests Of Justice"

For policy reasons, Human Rights Watch believes that the OTP should adopt a narrow reading of the phrase "interests of justice" that precludes practices that could lead to impunity for some of the worst crimes under the pretext of preserving peace and security.

Human Rights Watch is not insensitive to the ramifications of actions by the OTP on peace and security. We believe, however, that if the OTP formalizes regulations that publicly state that issues of peace and security are factors the prosecutor will consider in making determinations under Article 53, the prosecutor could: (a) risk being mired in making political judgments that would ultimately undermine his work; (b) risk subjecting the OTP to enormous political pressures and attempted manipulation by governments and rebel groups.

As expressed above, Human Rights Watch does not see the Rome Statute as suggesting that political factors constitute a legitimate basis for the prosecutor to base decisions under Article 53. We believe that for the OTP to be engaged in such decision-making has the potential for harming its work. It is a hard enough task for the OTP to evaluate the worst crimes and perpetrators, and gather evidence for prosecutions, without having to factor in how each indictment might impact upon local political stability.

Indictment of more major political figures are more likely to cause, or appear to cause, ramifications affecting peace and stability. Major political figures might also have enough weight to suggest that their indictments could cause instability, or threaten that their indictments could have such ramifications. In this way, the OTP's prosecutions of top level figures could be seriously undermined.

Additionally, if one party to a conflict wanted to undermine the OTP's work, it could simply launch a new initiative purportedly aimed at achieving peace or announce that it will be carrying out destabilizing activities or preclude peace talks. The prosecutor should always attempt to steer clear of such politicization of his role, and should certainly not adopt a construction of "the interests of justice" that would favor such politicization. This type of politicization could in turn undermine the legitimacy of the Court if the OTP were to be perceived as a body responsive to political pressure.

To permit consideration of whether prosecutions would harm peace talks or stability could also result in identical crimes being treated dissimilarly, or, even worse, more egregious crimes not being prosecuted in favor of lesser ones. Either of these results would undermine the perception of impartiality of the work of the OTP.

For situations of ongoing conflict, as well as post-conflict societies, any ICC investigation could be considered as a potential destabilizing factor and could be seen as inherently disruptive of any ongoing peace process. The interface of justice and peace is going to be a frequent, if not a constant, factor in all the situations the prosecutor of the ICC is going to be investigating, because of the nature of the crimes within the prosecutor's jurisdiction.

Allowing peace processes or political stabilization to dictate the ultimate fate of ICC prosecutions would undermine the objectives of the Rome Statute. It would mean that prosecutions should only occur well after crimes have been committed, long after instability has ceased. This would completely undermine any short-term deterrent value that the court might have through investigating or prosecuting current crimes.[52] The deterrent goals of the court would also be undermined if it appeared that prosecutions could be avoided by political manipulation based on issues of national stability.

Furthermore, our experience has been that justice itself can have tremendous value in contributing to peace and stability. The stigmatizing effect of criminal prosecutions helps isolate disruptive actors from the political scene and strengthen political stability. We have seen this, for example, in both Liberia and the Balkans. The indictments of former Liberian President Charles Taylor by the Sierra Leone Special Court,[53] and the indictments of Radovan Karadzic[54] and Ratko Mladic[55] by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia have undermined the political weight of those individuals and marginalized them from political life in their former countries. This marginalization of such figures has in turn contributed to strengthening peace and stability.

IV. The Type of Factors That Should Be Open For Consideration Regarding "The Interests Of Justice"

A. Gravity of the crime; the age or infirmity of the alleged perpetrator; his or her role in the alleged crime

Obviously, the factors explicitly articulated in the Rome Statute are ones the prosecutor should consider under Article 53. The prosecutor has invited comments as to how these terms should be construed.[56] In this respect, Human Rights Watch believes it is helpful to consider the case law of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). That case law, for example, discusses, in the context of evaluating crimes for purposes of sentencing: (i) the gravity of crimes; (ii) the age or infirmity of the alleged perpetrator; and (iii) the role of the alleged perpetrator.[57] While the context of sentencing is admittedly somewhat different from considering "the interests of justice," the decisions pertaining to sentencing nonetheless appear helpful to consider.

These decisions suggest that the gravity of crimes, for example, requires consideration of:

- the amount of premeditation and/or planning;[58]

- the scope and extent of the crimes;[59]

- the numbers of victims;[60]

- the ramifications to the victims-for example, the extent of physical and psychological suffering;[61] and

- the heinous means and methods used to commit the crimes.[62]

As to the age or infirmity of the alleged perpetrator, the decisions suggest, that, at least as to sentencing, the following may be factors to consider:

- the young age of the accused;[63]

- the poor health of the accused;[64] and

- the advanced age of the accused.[65]

Human Rights Watch, however, does not believe that poor health or advanced age are necessarily reasons why an investigation should not proceed. For example, just because perpetrators are of an advanced age, such as former Chilean President Augusto Pinochet[66] or surviving leaders of the former Khmer Rouge,[67] is no reason not to indict and attempt to prosecute such individuals, assuming they are mentally competent to stand trial. Poor health would have to preclude a trial if (a) it impacted upon a defendant's competence, or (b) the defendant's health were rapidly and ominously deteriorating to the point that he or she would be unlikely to live through trial. General poor health, however, such as that of former Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic currently on trial before the International Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia,[68] is no reason not to indict or try an individual.

ICTY and ICTR decisions also suggest that the "role of the alleged perpetrator" requires consideration of:

- how important a role the accused played regarding the crime;[69]

- whether the individual actually participated in the crimes directly,[70] or is otherwise responsible for the crimes, for example, by having planned or ordered others to carry them out;[71]

- the informed, voluntary, willing or enthusiastic participation in the crime.[72]

B. Whether there is a significant difference in the criteria under Article 53(1)(c) and Article 53(2)(c)

The prosecutor has also invited comments as to whether the prosecutor's discretion in deciding not to open an investigation (Article 53(1)(c)) is more restricted than in relation to a possible decision not to proceed with a prosecution (Article 53(2)(c)).[73] Under Article 53(1)(c), the criteria enumerated are only the "gravity of the crime" and "the interests of victims" whereas under Article 53(2)(c), the prosecutor is directed to consider "all the circumstances," and additional criteria expressly identified are "the age or infirmity of the alleged perpetrator" and "his or her role in the alleged crime."

Human Rights Watch takes the view that this difference between the two provisions was most probably not accidental. It is likely that Article 53(1)(c) does not require evaluation of "the age or infirmity of the alleged perpetrator" and "his or her role in the alleged crime" for the simple reason that when the prosecutor decides "whether to initiate an investigation" under Article 53(1), that occurs at quite an early stage, where the prosecutor, for example, may not yet have focused on particular perpetrators. In such circumstances, it would make no sense to evaluate such criteria.

At a later stage, when a decision is made under Article 53(2)(c), the prosecutor will have more information to evaluate. Also, the prosecutor does appear to have somewhat broader discretion in making a decision under Article 53(2)(c) than under Article 53(1)(c) because he is directed to consider "all the circumstances" as well as the additional criteria of "the age or infirmity of the alleged perpetrator" and "his or her role in the alleged crime."[74]

C. The interests of victims

One of the factors that the Prosecutor is directed to consider under both Article 53(1)(c) and 53(2)(c) before determining not to initiate an investigation or proceed from investigation to trial is "the interests of victims." Human Rights Watch believes that, for purposes of Article 53, that phrase must be construed to encompass those interests that directly further the interests of justice.

(i) Only "interests of victims" that promote the justice interests of the court are relevant for a determination under Article 53

Under Article 53, the prosecutor may decide not to initiate or proceed with an investigation if it would not serve the interests of justice, taking into account, inter alia, the "interests of victims." While victims may have many different interests related to an ICC prosecution and/or investigation, only those that relate to achieving justice are relevant for the purposes of Article 53. Relevant justice interests would include the need of victims to have their suffering publicly recognized, to know which perpetrators are responsible for which crimes, to hear the perpetrators' explanations as to why the crimes were committed and to see perpetrators punished. Other interests, while important, would not necessarily be related to whether a case is "in the interests of justice." For instance the needs of victims for reparations, medical treatment or education may be quite real, but that does not mean that those are relevant factors for determining which cases the ICC should investigate or prosecute. Likewise, it is not a justice interest whether some victims believe a prosecution will hurt chances for a peace settlement: their needs for justice, whether great or small, will remain unchanged. While the Prosecutor should always be receptive to hearing the views of victims, those views are not all necessarily relevant to a determination under Article 53.

In the same manner, the "interests of victims" towards processes such as truth commissions, national amnesties, or traditional reconciliation methods are unrelated to the justice interests of the Court. It would be contrary to the purposes of the Rome Statute and at odds with international law to have the worst perpetrators of the worst crimes not prosecuted based on such concerns.

Human Rights Watch also notes that, within the framework we suggest, should polling be used to help determine the justice interests of victims, an effort must be made to accurately determine such victims' justice interests. The prosecutor, in considering those interests, must be careful to rely upon reasonably accurate polling methods, or groups that accurately represent victims' interests, and not potentially politically motivated sources.

D. Other possible factors

As set forth above, Article 53(2)(c) states: "A prosecution is not in the interests of justice, taking into account all the circumstances, including the gravity of the crime, the interests of victims and the age or infirmity of the alleged perpetrator, and his or her role in the alleged crime." (emphasis added). Because the word "including" is present in Article 53(2)(c), it is clear that the factors enumerated in Article 53(2)(c) are not the only ones that may be considered by the prosecutor in making a determination under Article 53(2)(c).

Thus, for example, additional factors might include:

(i) the military rank or the governmental position of an alleged perpetrator;[75] or

(ii) whether a decision not to proceed would insult the memory of the victims.[76]

These factors are the same type of factors as those articulated in Article 53- namely, factors that are relevant to whether a particular case has merit or not. We believe that these are the appropriate type of additional factors to consider. Those factors articulated in Article 53(1)(c) and 53(2)(c) do not suggest that there should be consideration of broad criteria, such as the ramifications of an ICC investigation upon political stability.

Furthermore, as explained earlier, developments at the national level such as truth commissions, national amnesties, or the implementation of traditional reconciliation methods, or concerns regarding an ongoing peace process would not be appropriate factors to consider. It would be contrary to the object and purpose of the Rome Statute and international law to decide not to initiate an investigation or to cease a prosecution based on these criteria.

While the military rank or the governmental position of an alleged perpetrator is not expressly articulated as a factor, this is the type of additional factor that could be appropriate to consider. The jurisprudence of the two ad hoc tribunals has repeatedly reflected-albeit in the context of sentencing determinations-that persons who are entrusted with high offices owe duties of extra vigilance to protect those under their care.[77]

V. Limited Discretion as to Timing by the OTP

While, as discussed above, only the Security Council can officially defer an investigation or prosecution for reasons affecting international peace and security, there is still some discretion that must remain with the prosecutor regarding timing. There are many facets of an investigation that mandate prosecutorial discretion over timing. For example, the prosecutor would determine when he believes there is sufficient information gathered to apply for an arrest warrant.[78] Although there are certain mechanisms built into the Rome Statute for Pre-Trial Chamber review of the prosecutor's actions, nothing in the Rome Statute states, for example, that the prosecutor must ensure that a warrant is issued within a certain prescribed time after having commenced an investigation. At the same time, we are concerned that if the OTP explicitly agrees to defer the issuance of arrest warrants in order to enhance stability, states or rebel groups under investigation will have every incentive to attempt to manipulate the OTP by purporting to engage in peace efforts every time they believe issuance of an arrest warrant is near.

Any prosecutorial discretion that exists regarding timing also should not continue indefinitely. At a certain point, extensive delays can amount to de facto impunity, which would be contrary to the purposes of the Rome Statute. Furthermore, there is a danger of one or both sides to a conflict appearing to launch an initiative purportedly aimed at achieving peace, which is in fact a pretext in order to divert an ICC investigation. The prosecutor does not need to accept mere representations as to intentions to further peace negotiations.

Thus, we offer three specific caveats regarding prosecutorial discretion regarding timing of an investigation or the issuance of arrest warrants:

- (i) The prosecutor should not acknowledge publicly that he is delaying an investigation because of a national peace process. By making statements to that effect, the prosecutor makes himself susceptible to lobbying and political pressures, at the same time that the OTP is mandated by the Rome Statute to act independently;[79]

- (ii) Any delay should not be indefinite in a way that makes the investigation meaningless or results in de facto impunity.

- (iii) Simple representations about the intent to initiate a peace process, or peace negotiations that appear stalled, for example, should not suffice to trigger delay.

Conclusions and Recommendations

A. The OTP's current draft regulations regarding "the interests of justice" should be revised

In the current version of the Draft Regulations of the Office of the Prosecutor, there is no definition of "the interests of justice." A footnote states:

The experts are not in a position to make a recommendation on whether the Regulations should contain a further definition of what may constitute ‘interests of justice'. Were it to be decided that such definition be given, this could comprise the following factors: (a) the start of an investigation would exacerbate or otherwise destabilize a conflict situation; (b) the start of an investigation would seriously endanger the successful completion of a reconciliation or peace process; (c) the start of an investigation would bring the law into disrepute.[80]

Human Rights Watch believes that a definition of "the interests of justice" should be given, but that these three proposed criteria should be rejected. First, as explained above, there are certain criteria set forth in the Rome Statute regarding "the interests of justice," and clearly those that are enumerated need to be considered. Second, for the many reasons explained above, we do not view considerations of peace and stability to be appropriate considerations under Article 53. Finally, the phrase contained in the current draft regulations that the start of an investigation "would bring the law into disrepute" is too vague as to offer clear guidance.

B. Human Rights Watch's recommendations for regulations

Human Rights Watch suggests that the OTP adopt the following draft regulations:

1. In making a determination of "the interests of justice" under Article 53(1)(c), the factors to be considered are:

a. the gravity of the crime, including:

(i) the particular circumstances of the case;

(ii) the form and degree of the participation of the accused in the crime;

(iii) the amount of premeditation and/or planning;

(iv) the scope and extent of the crimes;

(v) the numbers of victims;

(vi) the ramifications to the victims-for example, the extent of physical and psychological suffering; and

(vii) the heinous means and methods used to commit the crimes.

b. the interests of victims, namely, those interests of victims that directly pertain to justice interests, such as the needs of victims:

(i) to have their suffering publicly recognized;

(ii) to know which perpetrators are responsible for which crimes;

(iii) to hear the perpetrators' explanations as to why the crimes were committed; and

(iv) to see perpetrators punished.

2. In making a determination of "the interests of justice" under Article 53(2)(c), the factors to be considered are:

a. the gravity of the crime;

b. the role played in the crime by the alleged perpetrator, considering, for example:

(i) whether the individual actually participated in the crimes directly;

(ii) whether the individual is otherwise responsible for the crimes, for example, by having planned or ordered others to carry them out;[81]

(iii) the informed, voluntary, willing or enthusiastic participation in the crime.

c. the interests of victims;

d. the personal circumstances of the accused, such as age and health, noting that the following may be factors to consider in certain situations:

(i) the young age of the accused;

(ii) the poor health of the accused; and

(iii) the advanced age of the accused.

e. additional factors of the same type, such as:

- (i) the military rank or the governmental position of the alleged perpetrator; or

- (ii) whether a decision not to proceed would insult the memory of the victims.

3. A decision whether or not to initiate an investigation or proceed to trial must not be influenced by:

a. possible political advantage or disadvantage to the government or any political party, group or individual;

b. possible media or community reaction to the decision.

C. The importance of publication of new draft regulations

We believe that regulations on the interpretation of the terms "interests of justice" are needed in order to have objective standards regarding Article 53 that could be applied in every situation.[82] The work of the court and the work of the prosecutor in particular will be subject to extensive public scrutiny. Perceptions of the prosecutor's work are and will be tremendously important.

We believe that the existence of regulations on the application of Article 53 could: ensure fairness and consistency in the way different cases are handled; help the prosecutor in the face of enormous pressure from the general public, the press, some NGOs and some victims to help maintain the impartiality of the OTP; and help in demonstrating that the ICC is a judicial institution and not prone to political manipulation.

The regulations should be reviewed and amended as needed in light of evolving practice. These regulations should be part of a final set of OTP regulations touching upon all aspects of the OTP's work.

[1] See Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, 17 July, 1998, A/CONF.183/9 (entry into force 1 July 2002) [hereinafter Rome Statute], Art. 53.

[2] While we are cognizant that Article 53(2)(c) directs the prosecutor to consider "all the circumstances" in making a determination regarding "the interests of justice," this language should be interpreted to mean all the circumstances that are appropriate to consider that are consistent with international law, and with the object and purpose of the Rome Statute.

[3] Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1155 U.N.T.S. 331, May 23, 1969, Art. 31.

[4] Rome Statute, Art. 21.

[5] Rome Statute, Art. 53.1(c).

[6] Rome Statute, Art. 53.2.

[7] Philippe Kirsch, the chairman of the Rome Diplomatic Conference, observed in an interview subsequent to the adoption of the Rome Statute that the language of Art. 53, particularly the phrase "the interests of justice," reflects a "creative ambiguity" toward the controversial issue of giving the prosecutor the power to recognize an amnesty exception to the court's jurisdiction. Michael Scharf, "The Amnesty Exception to the Jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court," Cornell International Law Journal, vol. 32 (1999), 507, 521-22. This view has also been expressed by Mahnoush Arsanjani, who served as the Secretary of the Committee of the Whole of the Rome Conference: "During the preparatory phase, the question of how to address amnesties and truth commissions was never seriously discussed . . . . The same evasive approach was taken at Rome." Mahnoush H. Arsanjani, "The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court," American Journal of International Law, vol. 22 (1999), p. 38. As a matter of treaty interpretation, one would not look to "the preparatory work of the treaty and the circumstances of its conclusion" except to "confirm" the meaning reached from considering, among other things: (i) the ordinary meaning of the treaty in context and in light of its object and purpose; and (ii) relevant rules of international law, or where the meaning is ambiguous or leads to a result "which is manifestly absurd or unreasonable." Vienna Convention, Art. 32.

[8] Direct use of the phrase "in the interests of justice" in relation to prosecutorial powers comes only twice, first from a delegate of the Syrian Arab Republic, who expressed his reservations about "allowing the Prosecutor to stop an investigation in the supposed interests of justice." United Nations Diplomatic Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court: summary records of the plenary meetings and of the meetings of the Committee of the Whole (U.N. Diplomatic Conference), 379, A/CONF.183/13 (Vol. II) (1998), available at http://www.un.org/law/icc/rome/proceedings/E/Rome%20Proceedings_v2_e.pdf. A delegate from Denmark, on the other hand, foresaw the possibility that "suspending a case would serve the interests of justice (ibid., p. 322), but did not elaborate on when such an occasion might occur. At a number of other points during the Rome Conference, the phrase is used in passing. A Kenyan delegate reaffirmed his nation's support of "a body free from political manipulation, pursuing only the interests of justice, with due regard to the rights of the accused and the interests of the victims." Ibid., p. 97. A delegate from Nepal argued that "[t]he interests of justice would be served if victims could also be made parties to the trial and be given the opportunity to obtain restitution from the assets of the perpetrator." Ibid., p. 119. And, a delegate from Spain urged that the ICC be equipped to "take all appropriate measures for the preservation of evidence and any other precautionary measures in the interests of justice." Ibid., p. 232. In speaking in defense of giving the prosecutor power to trigger ICC jurisdiction, a delegate from Trinidad and Tobago noted that it "might not be in the interests of justice in the long run" to limit jurisdictional triggering to States parties only. Ibid., p. 223.

[9] See Art. 53 (mandating Pre-Trial Chamber review regarding determinations of "interests of justice" under both Articles 53(1) and 53(2)).

[10] Rome Statute, Art. 16.

[11] Vienna Convention, Art. 31.1.

[12] For the full text, see Vienna Convention, Art. 31.2.

[13] Rome Statute, preamble ("Mindful that during this century millions of children, women and men have been victims of unimaginable atrocities that deeply shock the conscience of humanity, Recognizing that such grave crimes threaten the peace, security and well-being of the world.").

[14] Rome Statute, preamble (emphasis added).

[15] Otto Triffterer, "The Preventive and the Repressive Function of the International Criminal Court," in The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: A Challenge to Impunity, edited by Mauro Politi and Giuseppe Nesi (Aldershot: Ashgate Dartmouth, 2001), p.143.

[16] Luigi Condorelli & Santiago Vallalpando, "Deferral & Referral by the Security Council," in The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, A Commentary, edited by Antonio Cassese Paola Gaeta and John R.W. Jones (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 631.

[17] The phrase "in the interests of justice" is also found, for example, in the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal of the former Yugoslavia ("ICTY") and the Charter of Nuremberg International Military Tribunal ("IMT"). Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, S.C. Res. 827, (May 25, 1993), reprinted in 32 ILM 1203 (hereinafter "ICTY Statute"); London Charter of the International Military Tribunal, August 8, 1945 (hereinafter "IMT Charter"), available at http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/imt/proc/imtconst.htm. Article 21(4) of the ICTY Statute provides that the accused is entitled to have legal counsel assigned "where the interests of justice so require." ICTY Statute, Art. 21(4). Article 28 provides that issues related to pardoning or commutation of sentences shall be based on "the interests of justice." ICTY Statute, Art. 28; see also ICTR Statute, Art. 27. The phrase also appears several times in the IMT Charter. For instance, Article 25 permits translations of documents in the interest of justice. IMT Charter, Art. 25. In all of these contexts, the phrase "in the interests of justice" seems to emphasize so that justice may be administered fairly, or in order to ensure a proper prosecution.

[18] Rome Statute, Art. 55(2)(c).

[19] Article 61 permits a confirmation hearing in the absence of the person charged where that person has waived his or her right to be present or fled; in such circumstances, the person shall be represented by counsel if that is "in the interests of justice." Rome Statute, Art. 61(2)(b). Article 65 permits the Trial Chamber, after an accused has made an admission of guilt, to request the prosecutor to present additional evidence, or continue the trial, where that would be "in the interests of justice." Rome Statute, Art. 65(4). Article 67(1)(d) again deals with providing for legal assistance "where the interests of justice" so require. Rome Statute, Art. 67(1)(d).

[20] See ICC Rules of Procedure and Evidence, ICC-ASP/1/3, available at http://www.un.org/law/icc/asp/1stsession/report/english/part_ii_a_e.pdf [last viewed June 17, 2005], Rule 69 (providing that the parties may agree upon an alleged fact, although the Chamber may require a more complete presentation of that fact based on "the interests of justice"); Rule 73(6) (requiring consideration of "the interests of justice" in resolving the admissibility of evidence from the International Committee of the Red Cross); Rule 82(5) (regarding application of materials covered by Article 54(3)); Rule 100(1) ("where the Court considers that it would be in the interests of justice, it may decide to sit in a State other than the host State."); Rule 136(1) (the Trial Chamber may order separate trials based on "the interests of justice"); Rule 165(3) (allowing for written submissions on issues covered by Article 61, "unless the interests of justice otherwise require").

[21] Rome Statute, Art. 16.

[22] See Giuliano Turone, "Powers and Duties of the Prosecutor," in The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: A Commentary, edited by Antonio Cassese, Paola Gaeta & John R.W.D. Jones (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 1142 (emphasis added).

[23] Rome Statute, Art. 42(1).

[24] Turone, "Powers and Duties of the Prosecutor," p. 1143 (emphasis in original).

[25] See, e.g., Morten Bergsmo & Jelena Pejić, "Article 16 Deferral of Investigation or Prosecution," in Commentary on the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: Observers' Notes, Article by Article, edited by Otto Triffterer (Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 1999), p. 377.

[26] Ibid., p. 378, para. 10.

[27] Ibid., p. 377, para. 7.

[28] Turone, "Powers and Duties of the Prosecutor," p. 1143 (arguing that such a deferral is justified by the fact that "the duty and power to guarantee international peace and security does belong to the Security Council").

[29] See Rome Statute, Art. 8.1 ("The Court shall have jurisdiction in respect of war crimes in particular when committed as a part of a plan or policy or as part of a large-scale commission of such crimes.").

[30] "[A]rticle 16 provides an unprecedented opportunity for the Council to influence the work of a judicial body." Triffterer, Commentary on the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: Observers' Notes, Article by Article, p. 377.

[31] Clearly, the Security Council's twelve month deferrals under Article 16 should not be renewed over and over in order to create an indefinite deferral, as that would result in de facto immunity. If that were to occur, both international law and the purpose of the Rome Statute would be undermined. Article 16, of course, also must not be misused, as it was for example in Resolution 1422, where the Security Council purportedly acting under its Chapter VII powers granted a prospective exemption for "current or former officials or personal" from troop contributing countries from ICC prosecution. S/Res/1422 (2002); Mohamed El-Zeidy, "The United States Dropped the Atomic Bomb of Article 16 of the ICC Statute: Security Council Power of Deferrals and Resolution 1422," Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law, vol. 35 (2002) p. 1503 (arguing that Resolution 1422, by essentially calling for an indefinite deferral, undermines international law and the spirit of the Rome Statute); Andreas L. Paulus, "Legalist Groundwork for the International Criminal Court," European Journal of International Law, vol.14 (2003), p. 843, available at http://www.ejil.org/journal/vol (discussing Resolution 1422: "The fear that Council deferral would become a threat to judicial independence of the Court. . . has thus been realized even before the Court has tried its first case.").

[32] Provisions of the Rome Statute take great care to shield the court's officials, including the prosecutor, from political influence. For example, Article 42 emphasizes that the prosecutor shall act independently, and "shall not seek or act on instructions from any external source," and, under Article 45, all officers, including the prosecutor, must make a "solemn undertaking" of impartiality.

[33] Vienna Convention, Art. 31.3(c).

[34] Rome Statute, Art. 21.

[35] M. Cherif Bassiouni, International Extradition: United States Law and Practice (Dobbs Ferry: Oceana Publications, 1987), p. 22. See also M. Cherif Bassiouni and Edward M. Wise, Aut Dedere Aut Judicare: The Duty to Extradite or Prosecute in International Law (Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1995), pp. 20-25.

[36] Samantha Ettari, "A Foundation of Granite or Sand? The International Criminal Court and United States Bilateral Immunity Agreements," Brooklyn Journal of International Law, vol. 30 (2004), 205, 232.

[37] Ibid., p. 247 (citing Giuseppe Nesi, "The Obligation to Cooperate with the International Criminal Court and States Not Party to the Statute," in The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: A Challenge to Impunity, edited by Mauro Politi and Giuseppe Nesi [Aldershot: Ashgate Dartmouth, 2001], p. 223).

[38] Michael J. Kelly, "Cheating Justice by Cheating Death: The Doctrinal Collision for Prosecuting Foreign Terrorists -- Passage of Aut Dedere Aut Judicare into Customary Law & Refusal to Extradite Based on the Death Penalty," Arizona Journal of International & Comparative Law, vol. 20 (2003), 491, 497.

[39] William A. Schabas, "Justice, Democracy, and Impunity in Post-genocide Rwanda: Searching for Solutions to Impossible Problems," Criminal Law Forum, vol. 7 (1996), 523, 555.

[40] Jordan J. Paust, International Law as Law of the United States (Durham: Carolina Academic Press, 1996), p. 405 (emphasis added).

[41] Chet J. Tan, Jr., "The Proliferation of Bilateral Non-Surrender Agreements Among Non-Ratifiers of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court," American University International Law Review, vol.19 (2004), 1115, 1163 (explaining universal jurisdiction's purpose is to "enhance world order" by holding those who have committed certain crimes accountable); see also George William Mugwanya, "Expunging the Ghost of Impunity for Severe and Gross Violations of Human Rights and the Commission of Delicti Jus Gentium: A Case for the Domestication of International Criminal Law and the Establishment of a Strong Permanent International Criminal Court," Michigan State University-DCL Journal of International Law, vol. 8 (1999), 701, 757-758 (noting that if states indeed were to try to deny the criminal responsibility of an individual, this would run contrary to the principles of criminal responsibility recognized by customary international law).

[42] The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Genocide Convention) states: "Persons committing genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III shall be punished, whether they are constitutionally responsible rulers, public officials or private individuals." Genocide Convention, adopted by Resolution 260(III)A of the United Nations General Assembly, December 9, 1948, Art. 4.

[43] Article 146 of the Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Times of War (Geneva IV) requires that "[t]he High Contracting Parties undertake to enact any legislation necessary to provide effective penal sanctions for persons committing, or ordering to be committed, any of the grave breaches of the present Convention defined in the following Article." Geneva IV, opened for signature Aug. 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3516, 75 U.N.T.S. 287, Art. 146.

[44] Commentators suggest that customary international law requires states to prosecute individuals accused of committing crimes against humanity. See, e.g., Jordan J. Paust, "The Reach of ICC Jurisdiction Over Non-Signatory Nationals," Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law, vol. 33 (2000), 1, 14 ("International law ... simply does not permit immunity of a person accused of customary international crime."); Roman Boed, "The Effect of a Domestic Amnesty on the Ability of Foreign States to Prosecute Alleged Perpetrators of Serious Human Rights Violations," Cornell International Law Journal, vol. 33 (2002), 297, 314 ("Crimes against humanity, unlike genocide or torture, are not the subject of a specialized convention compelling States to take particular action. Consequently, any duty to prosecute alleged offenders of crimes against humanity must be based on custom"); Naomi Roht-Arriaza, "Comment, State Responsibility to Investigate and Prosecute Grave Human Rights Violations in International Law," California Law Review, vol. 78 (1990), 451, 489 ("Three sources suggest that there is an emerging obligation under customary international law to investigate grave human rights violations and take action against those responsible: (1) . . . treaty provisions and judicial decisions . . .; (2) state practice, including adherence to U.N. resolutions and state representations before international bodies; and (3) the law of state responsibility of injury to aliens, as updated in light of human rights law.")

[45] Rome Statute, preamble (emphasis added).

[46] Daniel W. Schwartz, "Rectifying Twenty-Five Years of Material Breach: Argentina and the Legacy of the ‘Dirty War' in International Law," Emory International Law Review, vol. 18 (2004), 317, 342-43 (emphasis added).

[47] Appeals Chamber, Special Court for Sierra Leone, Decision on Challenge to Jurisdiction: Lomé Accord Amnesty, p. 29, para. 71, March 13, 2004 (emphasis added) ("the amnesty granted by Sierra Leone cannot cover crimes under international law that are the subject of universal jurisdiction" because "it stands to reason that a state cannot sweep such crimes into oblivion and forgetfulness which other states have jurisdiction to prosecute by reason of the fact that the obligation to protect human dignity is a peremptory norm and has assumed the nature of obligation erga omnes"); separate opinion of Justice Robertson in Prosecutor v. Allieu Kondewa (Appeals Chamber), p. 24, para. 47, May 25, 2004. ("There is a substantial body of cases, comments, rulings and remarks which denies the permissibility of amnesties in international law for crimes against humanity and war crimes.")

[48] William A. Schabas, "Amnesty, the Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Special Court for Sierra Leone," U.C. Davis Journal of International Law & Policy, vol. 11 (2004), 145, 148-49 (emphasis added).

[49] Ibid., p. 149.

[50] Ibid.

[51] For example, the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action reads: "States should abrogate legislation leading to impunity for those responsible for grave violations of human rights such as torture and prosecute such violations, thereby providing a firm basis for the rule of law." World Conference on Human Rights, U.N. GAOR, 48th Sess., U.N. Doc. A/CONF.157/23, para. 60 (1993). In October 2000, the UN Secretary-General reported to Security Council that the United Nations has consistently maintained the position that "amnesty cannot be granted in respect of international crimes, such as genocide, crimes against humanity or other serious violations of international humanitarian law." Carsten Stahn, "Accomodating Individual Criminal Responsibility and National Reconciliation: The UN Truth Commission for East Timor," American Journal of International Law, vol. 95 (2001), 952, 955 (citing Report of the Secretary-General on the Establishment of a Special Court for Sierra Leone, UN Doc. S/2000/915, para. 22). See also Schabas, "Amnesty, the Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Special Court for Sierra Leone," p. 145 (The U.N. recognizes that amnesty is prohibited for serious crimes and States have a duty to "prosecute or extradite."). The recent Report of the Secretary-General on The Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies declares that states should: "[r]eject any endorsement of amnesty for genocide, war crimes, or crimes against humanity, including those relating to ethnic, gender and sexually based international crimes, [and] ensure that no such amnesty previously granted is a bar to prosecution before any United Nations-created or assisted court." Report of the Secretary General, The Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies, U.N. SCOR, S/2004/616 at p. 21; see also Diane Orentlicher, Independent Study on Best Practices, Including Recommendations, to Assist States in Strengthening their Domestic Capacity to Combat All Aspects of Impunity, U.N. ESCOR, 60th Sess., Agenda Item 17, paras. 27-35, U.N. Doc. E/CN.4/2004/88, Feb. 27, 2004 (issued pursuant to E.S.C. Res. 2003/72).

The U.N. Commission on Human Rights, in a resolution that proclaimed the importance of combating impunity for all human rights violations that constitute crimes has also stressed not only the duty to "prosecute or extradite" but that truth commissions are complements to, not substitutes for, a justice process. UN Commission on Human Rights, Impunity, resolution 2002/79, para.10 ("Welcomes in this regard the establishment in some States of commissions of truth and reconciliation to address human rights violations that have occurred there, welcomes the publication in those States of the reports of those commissions and encourages other States where serious human rights violations have occurred in the past to establish appropriate mechanisms to expose such violations, to complement the justice system") (emphasis added).

[52] See Otto Triffterer, "The Preventive and the Repressive Function of the ICC," p. 143 ("The Rome Statute mentions the prevention of crimes falling within the jurisdiction of the Court in paragraph 5 of its Preamble. It follows from the context that to prevent crimes under international criminal law is the main purpose and the mission of the Court, in order to guarantee ‘lasting respect for the enforcement of international justice'. . . .").

[53] Indictment, Prosecutor v. Charles Ghankay Taylor, Case No. SCSL-03-01-I-001, March 7, 2003, available at: http://www.sc-sl.org/Documents/SCSC-03-01-I-001.pdf.

[54] Amended Indictment, Prosecutor v. Radovan Kardzic, April 28, 2000, available at: http://www.un.org/icty/indictment/english/kar-ai000428e.htm.

[55] Amended Indictment, Prosecutor v. Ratko Mladic, Case No. IT-95-5/18-I, Oct. 10, 2002, available at: http://www.un.org/icty/indictment/english/mla-ai021010e.htm.

[56] Meeting of the Office of the Prosecutor with Non-Governmental Organizations, November 30, December 1, 2005, "Consultation Proposal on the Interests of Justice."

[57] See generally Human Rights Watch, Genocide, War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity: Topical Digests of the Case Law of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2002), pp. 74-86, 235-62, available at https://www.hrw.org/reports/2004/ij/.

[58] Prosecutor v. Krstic, Case No. IT-98-33 (Trial Chamber), August 2, 2001, para. 711: ("Premeditation may ‘constitute an aggravating circumstance when it is particularly flagrant' and motive ‘to some extent [is] a necessary factor in the determination of sentence after guilt has been established.' When a genocide or a war crime, neither of which requires the element of premeditation, are in fact planned in advance, premeditation may constitute an aggravating circumstance. Premeditated or enthusiastic participation in a criminal act necessarily reveals a higher level of criminality on the part of the participant. In determining the appropriate sentence, a distinction is to be made between the individuals who allowed themselves to be drawn into a maelstrom of violence, even reluctantly, and those who initiated or aggravated it and thereby more substantially contributed to the overall harm."); Prosecutor v. Blaskic, Case No. IT-95-14 (Trial Chamber), March 3, 2000, para. 793 ("The premeditation of an accused in a crime tends to aggravate his degree of responsibility in its perpetration and subsequently increases his sentence."); Prosecutor v. Serushago, Case No. ICTR-98-39 (Trial Chamber), February 5, 1999, Sentencing Judgment, para. 27-30 (the Chamber considered as an aggravating circumstances the fact that the accused "committed the crimes knowingly and with premeditation").

[59] Prosecutor v. Plavsic, Case No. IT-00-39 & 40/1 (Trial Chamber), Feb. 27, 2003, para. 52 ("The gravity [of offences] is illustrated by: the massive scope and extent of the persecutions; the numbers killed, deported and forcibly expelled; the grossly inhumane treatment of detainees; and the scope of the wanton destruction of property and religious buildings.").

[60] Ibid; see also Prosecutor v. Semanza, Case No. ICTR-97-20 (Trial Chamber), May 15, 2003, para. 571 (stating the number of victims killed by Semanza was an aggravating factor).

[61] Prosecutor v. Krstic, Case No. IT-98-33, para. 703 ("[T]he circumstance that the victim detainees were completely at the mercy of their captors, the physical and psychological suffering inflicted upon witnesses to the crime, the ‘indiscriminate, disproportionate, terrifying' or ‘heinous' means and methods used to commit the crimes are all relevant in assessing the gravity of the crimes. . . . Appropriate consideration of those circumstances gives ‘a voice' to the suffering of the victims.").

[62] Ibid.; see also Prosecutor v. Kayishema and Ruzidana, Case No. ICTR-95-1-T, Sentencing Order (Trial Chamber), May 21, 1999, para. 18 (considering the "heinous means" by which the defendants committed the crimes to be an aggravating factor).

[63] See, e.g., Prosecutor v. Serushago, Case No. ICTR-98-39 (Trial Chamber), February 5, 1999, para. 39-42 (The Chamber considered individual circumstances, including the accused's young age, as mitigating circumstances); Prosecutor v. Erdemovic, Case No. IT-96-22 (Trial Chamber), March 5, 1998, para. 16 (the Trial Chamber held that the combination of [Erdemovic's] young age [26 years old], evidence that he is "not a dangerous person for his environment," and "his circumstances and character indicate that he is reformable and should be given a second chance to start his life afresh upon release, whilst still young enough to do so.").

[64] Prosecutor v. Rutaganda, Case No. ICTR-96-3 (Trial Chamber), December 6, 1999, para. 471-73 (the Chamber considered Rutaganda's poor health to be a mitigating circumstance).

[65] Prosecutor v. Plavsic, Case No. IT-00-39&40/1 (Trial Chamber), February 27, 2003, para. 95-106 ("[T]he Trial Chamber considers that it should take account of the [advanced] age of the accused and does so for two reasons: First, physical deterioration associated with advanced years makes serving the same sentence harder for an older than a younger accused. Second, . . . an offender of advanced years may have little worthwhile life left upon release. [T]he Trial Chamber considers as a mitigating factor the advanced age of the accused.").

[66] There have been proceedings against former Chilean President Augusto Pinochet in both the UK (as a result of a Spanish investigation) and Chile. See, e.g., Regina v. Bartle and the Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis and Others Ex Parte Pinochet, Regina v. Evans and Another and the Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis and Others Ex Parte Pinochet, [1999] 2 W.L.R. 827 (H.L.); Resolución de la corte suprema que ratifica el desafuero a Augusto Pinochet, August 26, 2004, available at: http://www.emol.com/noticias/documentos/desafuero_pinochet.asp.

[67] A limited number of former Khmer Rouge are anticipated to stand trial in Cambodia. See, e.g., Law on the Establishment of Extra Ordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia for the Prosecution of Crimes Committed During the Period of Democratic Kampuchea, as adopted by National Assembly on January 2, 2001, available at: http://khmersenate.org/06-01-01.htm.

[68] Prosecutor v. Milosevic, Case No. IT-01-50-I (Trial Chamber), December 13, 2001.

[69] Prosecutor v. Naletilic and Martinovic, Case No. IT-98-34 (Trial Chamber), March 31, 2003, para. 744. ("[T]he sentence imposed should reflect the relative significance of the role of the accused in the context of the conflict in the former Yugoslavia. However, this has been interpreted to mean that even if the position of an accused in the overall hierarchy in the conflict in the former Yugoslavia was low, it does not follow that a low sentence is to be automatically imposed.").

[70] Prosecutor v. Ruggiu, Case No. ICTR-97-32-I (Trial Chamber), June 1, 2000, para. 53-80 (the Chamber considered the following to be mitigating circumstances: the accused's position with Radio Television Libres des Milles Collines and in political life [i.e., he was a subordinate at the radio station and played no part in formulating editorial policy] and the fact that he did not personally participate in the killings).

[71] Prosecutor v. Krnojelac, Case No. IT-97-25 (Trial Chamber), March 15, 2002, para. 77 ("There are, for example, circumstances in which a participant in a joint criminal enterprise will deserve greater punishment than the principal offender deserves. The participant who plans a mass destruction of life, and who orders others to carry out that plan, could well receive a greater sentence than the many functionaries who between them carry out the actual killing.").

[72] Prosecutor v. Blaskic, Case No. IT-95-14 (Trial Chamber), March 3, 2000, para. 792 ("Informed and voluntary participation means that the accused participated in the crimes fully aware of the facts. The importance of this factor varies in case-law depending on the degree of enthusiasm with which the accused participated. Informed participation is consequently a less aggravating circumstance than willing participation. Not only does the accused's awareness of the criminality of his acts and their consequences and of the criminal behaviour of his subordinates count but also his willingness and intent to commit them. Once such intent is established, it is likely to justify an additional aggravation of the sentence."); Prosecutor v. Tadic, Case No. IT-94-1 (Trial Chamber), November 11, 1999, para. 20 ("Consideration must also be given to the willingness of Dusko Tadic to commit the crimes and to participate in the attack. . . .").

[73] Meeting of the Office of the Prosecutor with Non-Governmental Organizations, November 30, December 1, 2005, "Consultation Proposal on the Interests of Justice."

[74] As noted above, Human Rights Watch interprets "all the criteria" to mean all the criteria that would be permissible to consider that are consistent with international law, and with the object and purpose of the Rome Statute.

[75] Turone, "Powers and Duties of the Prosecutor," p. 1174. Turone also includes: (i) the significance of the legal issues involved in the case; and (ii) the prospects for arresting the suspect. Ibid. We do not agree that whether a case has significant legal issues should be a factor to consider, since the prosecutor's mandate is to prosecute the most heinous crimes, regardless of whether they involve interesting or novel legal issues. Similarly, we also do not agree that the prospects for arrest should be a factor to consider because of this same mandate. If the person is not capable of being arrested, there may be no trial, but that is no reason why the indictment should not issue.

[76] While the language of the Rome Statute phrases this as "the interests of victims," Giuliano Turone formulates the inquiry in this way. We find Turone's formulation particularly helpful. Turone, "Powers and Duties of the Prosecutor," p. 1174.