(Beirut) – Qatar should enact further reforms on working hours, a safe working environment, inspections, and recruitment fees to protect migrant domestic workers, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

Law No. 15 on service workers in the home (“Domestic Workers Law”), ratified in August 2017, guarantees workers a maximum 10-hour workday, a weekly rest day, three weeks of annual leave, and an end-of-service payment. However, domestic workers still have fewer protections than other workers.

“Almost a year ago, Qatar passed a law providing legal protections for domestic workers’ rights for the first time,” said Rothna Begum, Middle East women’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Qatar should now address the gaps in the domestic workers’ law, and make sure that it is enforced.”

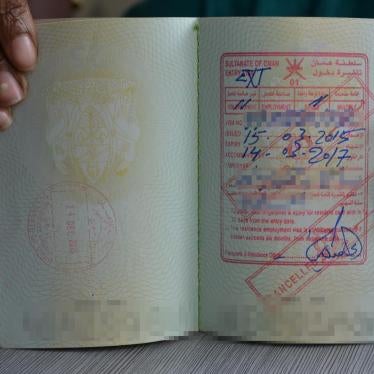

Human Rights Watch and other organizations have documented abuses of domestic workers in Gulf states, including in Qatar. They include long workdays with no rest and no days off, indebtedness from recruitment fees, confiscation of passports by employers, delayed and unpaid wages, confinement to the employer’s house, and in some cases, physical, verbal, or sexual assault.

The new law introduced labor protections for 173,742 domestic workers, mostly from Asia or East Africa, and including 107,621 women, according to the country’s 2016 labor force survey. But these workers are still vulnerable to abuse. Human Rights Watch details areas in which the law falls short of the International Labour Organization (ILO) Domestic Workers Convention, the global treaty on domestic workers’ rights. The report includes responses from the Qatari authorities.

The Domestic Workers Law provides that domestic workers can work up to 10 hours a day, but the country’s main labor law limits workdays to 8 hours and the work week to 48 hours. Unlike the labor law, the Domestic Workers Law does not set a limit on additional working hours or provide for overtime pay. It also allows domestic workers to work on rest days if they agree to it. But Human Rights Watch research has shown how the deep power imbalance between employers and domestic workers can make it extremely difficult for a worker to claim their rights, or refuse an employer’s request.

The Domestic Workers Law also fails to state that “on-call” hours should be regarded as hours of work and that workers may leave the household during rest periods and weekly rest days.

“Excessive working hours is one of the most common labor complaints by migrant domestic workers, especially because they live in their workplace,” Begum said. “Specific and strong protections to prevent overwork are particularly important for domestic workers.”

While the Domestic Workers Law requires employers to provide domestic workers with food and adequate accommodation, it is vague on minimum standards. The law also does not establish guidelines on domestic workers’ right to a safe and healthy working environment.

In November 2017, Qatar announced a temporary minimum wage of QR750 (US$206) for migrant workers, but this does not combat the current discriminatory practice of wage differentials based on nationality of domestic workers. Qatar is in the process of setting a minimum wage with the support from the ILO.

The International Trade Union Confederation has said that Qatar has committed to establishing workers’ committees in each workplace, with workers electing their own representatives. However, it is not clear whether there is a plan to tailor this system for domestic workers, who are typically dispersed across separate households.

Qatar’s kafala (sponsorship) system gives employers excessive control over domestic workers, including the power to deny them the right to leave the country or change jobs, Human Rights Watch said. Unless Qatar abolishes or significantly reforms this system, it will remain difficult for domestic workers to exercise their rights under the new law as they can be arrested and deported for “absconding” if they flee their employer’s home. Financial barriers can prevent domestic workers from pursuing claims of abuse, as the kafala system prevents them from working for another employer while a claim is being adjudicated.

In October 2017, Qatar signed a technical cooperation agreement (2018-2020) with the ILO, including a commitment to carry out the Domestic Workers Law and to replace the kafala system. On April 30, the ILO inaugurated its first project office in Qatar for a three-year cooperation program to achieve these commitments.

Qatar should ensure that it includes domestic workers in all of its labor reforms, with attention to their needs based on the specific characteristics of such work, Human Rights Watch said.

“Qatar should dismantle the kafala system entirely,” Begum said. “Qatar should ensure that migrant workers, including domestic workers, can change employers and leave the country without requiring employer permission at any time.”