(ナイロビ)― 南スーダン南部の街イェイの内部と周辺ではこの数ヶ月間、南スーダン政府軍と反政府勢力による民間人への深刻な人権侵害が起きていると、ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは本日述べた。具体的には、政府軍による殺害やレイプ、恣意的拘禁、また反政府軍による拉致などだ。ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチが今回イェイで確認した人権侵害は、現在の紛争で両勢力が行ってきた一連の民間人攻撃の最も最近の事件といえる。

スーダン人民解放軍(SPLA)と反政府勢力との戦闘、および両勢力による民間人攻撃が同国南部で激しくなったのは、2016年7月初めの首都ジュバでの一連の衝突後。民間人数十万人が南部のエクアトリア地域(Greater Equatoria)から逃れている。

「国連による武器禁輸措置の提案がようやく協議される。これまで南スーダンでは、ほぼ3年にわたり武装組織による民間人への残虐行為があった」と、ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチのアフリカ・アドボカシー上級ディレクターのダニエル・ベケレは述べた。「国連安全保障理事会メンバーは、民間人攻撃の停止の一助となりうるこの措置をただちに支持すべきである。」

War has reached Yei, and South Sudan’s civil war has turned this once-peaceful town upside down.

Read:11月19日から26日にかけて、ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは中央エクアトリアに新設されたイェイ川州の新州都イェイで被害者と目撃者70人以上に話を聞いた。イェイは首都ジュバから150kmだ。治安が悪化しているため、調査員らがムグウォ(Mugwo)、ルベケ(Rubeke)、ミティカ(Mitika)などイェイの周辺地域やラス(Lasu)に通じる街道一帯で直接状況を評価することはできなかった。これらの地域は、更に深刻な人権侵害が起きていると言われている地域だ。調査員らはイェイの政府職員とジュバの援助機関にもインタビューした。

南スーダン内戦では2013年12月の紛争勃発以来、政府軍と反政府勢力(スーダン人民解放運動反対派:SPLM-IO[マシャル前大統領派])構成員による民間人攻撃が顕著だ。2015年8月には、両勢力指導者が国民統一暫定政府設置などで合意したにもかかわらず、従来は安定していた地域でも現在も衝突や戦闘が起きている。

イェイの住民はヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチに対し、身の毛もよだつような民間人殺害、拘束と戦闘への恐怖により、7月からイェイと周辺地域では大勢の人びとが避難していると語った。イェイは政府軍が掌握しているが、反政府側が周辺地域の大半を手中に収めた模様だ。

国連難民高等弁務官事務所(UNHCR)はイェイの町に駐在しているが、人権侵害の報告があってから国連PKO部隊が哨戒を実施できたのはわずか2回。主な原因は、国連側のジュバの出入りに政府が制限を加えているからだ。

8月23日の殺害事例では、正体不明の襲撃者たちが家に押し入り、母親と娘(4)を手斧で殺し、遺体を川に捨てたと伝えられる。幼児(4ヶ月)は首を切りつけられたが生き残った。殺害は政府軍支配地域で起きたが、この事例やその他の事例でも、ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは襲撃犯が政府軍か反政府勢力のどちらかであるかを確認できなかった。

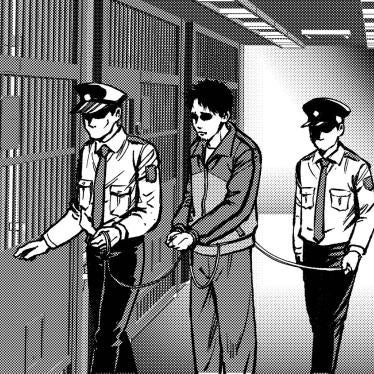

ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは、政府軍兵士が民間人男性をイェイの軍事施設に恣意的に拘禁した事例を多数明らかにした。またジュバ、ヤンビオ、ワウでの軍による恣意的拘禁について、現在の典型的なタイプも示している。イェイの信頼できる消息筋によれば、被拘禁者は拷問を受け、悲惨な環境に置かれている。少なくとも2人が強制失踪の被害に遭っているが、当局は拘禁を否定しており、所在は不明だ。強制失踪はいかなる状況の下でも禁止されており、戦争犯罪に該当することがある。

ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチの調査員はまた、マシャル前大統領率いる反政府勢力と連携していると主張するゲリラ側が、イェイから逃れている民間人を乗せた車列を待ち伏せ攻撃した事例も確認した。犠牲者の大半がキール大統領と広い意味で同じエスニック・グループであるディンカの人びとだった。「銃撃が始まったので身を伏せました」と、ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチのインタビューに対し、少年(11)は10月8日の車列襲撃事件の様子を語った。「他の人たちが僕の上に倒れかかってきました。1人は頭を打ち抜かれていました。」 ゲリラはトラックと中にまだ残っている人たちに火を放ち、中にいる数十人も殺害した。

政府軍兵士と反政府勢力戦闘員はともに、2016年半ばにイェイと周辺地域で紛争が激しくなって以来、女性や少女をレイプしていると、被害者、医療従事者、NGO関係者、政府職員は述べた。反政府勢力戦闘員は、イェイの南にあるキャンプに住むヌバ(Nuba)山脈出身の難民を襲撃し、少なくとも女性とその子ども計9人を拉致している。

ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチがインタビューした人はほぼ口をそろえて、民間人がイェイから自らの畑も含めた周辺地域に移動することがかなり難しいと語った。政府軍や反政府武装勢力がいるためだ。

国際法では、紛争時に広範な治安上の理由に基づき民間人を逮捕・拘引することは禁じられていないものの、拘禁は厳密なデュー・プロセスに従わねばならず、こうした手続き上の保護措置が尊重されなければ拘禁は恣意的とされる。とくにあらゆる被逮捕者は逮捕理由を告げられ、起訴または釈放を判断するため判事に迅速に面会し、拘禁の合法性に異議を申し立てる機会を与えられるべきである。

南スーダン政府は治安と移動の自由を確保するとともに、イェイで支援を求める民間人への援助機関のアクセスを許可し、ポスト・レイプ・ケア用の緊急医薬品を含む、緊急性の高い基礎医薬品についてイェイ市民病院への搬入を認めるべきだ。南スーダン政府は女性の権利擁護団体等に対し、心理社会的支援を含めた緊急のポスト・レイプ・ケアの重要性に関する啓発キャンペーンを支援すべきであると、ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは述べた。

国連安全保障理事国は、米国による武器禁輸と対象限定型制裁の提案を支持すべきだ。また南スーダンについてアフリカ連合(AU)によるハイブリッド刑事法廷設置作業を進めるよう強く求めるべきだ。法廷では、戦争犯罪など紛争下での深刻な武力紛争法違反の責任者について捜査と訴追が行われる。

「今回の恐るべき紛争は、南スーダンの民間人に甚大な被害をすでにもたらしているが、それは更に悪化している。誰一人として重大犯罪の責任を問われないことがその大きな理由だ」と、前出のベケレ・ディレクターは指摘する。「国連、アフリカ連合、またこの問題の主要国は、武器禁輸のほか、個人制裁やアフリカ連合によるハイブリッド刑事法廷など、一連の措置をただちに支持すべきだ。それによって国際犯罪の実行者の責任追及が可能となるのである。」

A Spreading Conflict

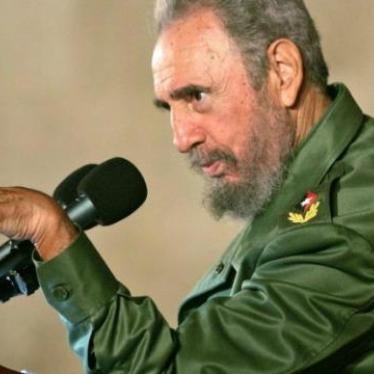

In July 2016, just two months after Riek Machar, the leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition (IO), resumed his role as first vice-president in a transitional national unity government planned under the August 2015 peace agreement, his forces and government soldiers fought in the capital, Juba. Serious human rights violations marked the fighting. Government forces killed civilians and raped women perceived to belong to Machar’s Nuer ethnic group.

Government troops have arbitrarily arrested and detained scores of civilians, subjecting them to inhumane treatment for prolonged periods of time. Human Rights Watch identified two cases of enforced disappearances by the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) military intelligence. Soldiers also killed and raped civilians, and the army forcefully displaced thousands of civilians from certain areas in Yei, shooting threateningly in the air and the bushes, then looting homes and belongings.

Human Rights Watch researchers documented a dozen killings inside of Yei. In most cases, relatives and witnesses said they believed the army was responsible. Human Rights Watch received allegations of many other cases of killings outside of Yei, but was unable to verify them because of movement restrictions and the lack of security.

Human Rights Watch also documented dozens of arbitrary arrests and detention and torture of civilians in Yei since May by government forces, especially army military intelligence and South Sudan’s national security service.

Researchers documented two cases of enforced disappearances by government forces in Yei.

Human Rights Watch documented two cases of rape by SPLA soldiers. In another incident, two girls were raped by armed men they believed to be SPLA soldiers who were not in uniform. All four rapes took place during the week Human Rights Watch spent in Yei. Human Rights Watch also collected several credible reports of other incidents of rape by SPLA soldiers in Yei.

Forced Displacement

Multiple witnesses told Human Rights Watch that on September 11, government forces entered the Dem, Sopiri, and Lutaya neighborhoods of Yei, shooting in the air and the bushes and ordering civilians to leave the areas. Soldiers then looted homes. One displaced resident said:

“I was in church and when I came out, one of the soldiers told me ‘What are you doing here, this place is only for rebels.’ He told me I had to leave. Then they looted the area completely. No one can go back to Dem now, the women are afraid of being raped and the men are afraid of being killed by the soldiers.”

Another former resident said that rebels had come to the neighborhoods to tell people in churches they should leave the area. “They came for two weeks before the SPLA came and they warned us that we should leave the area because they wanted to fight the SPLA,” she said. “When the SPLA came, we were chased out. I saw them shooting in the air scaring people and breaking houses, they took two of my goats.”

The laws of war prohibit the forcible displacement of civilians except for their own security or for imperative military reasons.

Rebel Abuses Against Civilians

Rebels belonging to ethnic groups populating the Greater Equatoria region and operating around Yei appeared to have targeted civilians of Dinka and Nuba ethnicity on the basis of their perceived affiliation to the government.

Attacks on Civilian Convoys

Rebels have increasingly been accused of targeting Dinka civilians, especially along the main roads leading to Juba from the Equatorias. On October 8, rebels operating north of Yei attacked a civilian convoy transporting mostly Dinka civilians from Yei to Juba. More than two dozen civilians were killed.

“It was a surprise attack,” said the truck driver. “They had AK-47 and a RPG. They only attacked my truck. We were in the middle of the convoy. I was transporting about 70 people, most of them were women and children.”

A survivor said that her 8-year-old son was killed in the attack: “I was standing in the middle of the truck when they started to shoot. Some around me died. My son Victor was among them. I didn’t see at first but a wounded woman with a 4-month baby saw him dead first and said ‘Be strong.’ She died later.”

A wounded 13-year-old boy, with three bullets in his body, said his brother died during the attack. Once the attackers stopped shooting, all survivors who were interviewed said the rebels lit the truck on fire.

“There was a woman – her name was Nyalam – and she died inside the truck with her 1-month baby. She was my co-wife,” said a 29-year-old grieving mother who survived the attack. “There was also Nyankim, my 12-year-old niece, Agwer, my 5-year-old son, and Adhiu my 3-year-old son. They all died.”

Rape and Sexual Violence

On at least two occasions in September, rebels entered the Lasu refugee camp, south of Yei. There, they raped two Nuba women and abducted nine women and their children. Their whereabouts remain unknown.

A witness to one of the abductions said they pointed guns at him and gathered men, women, and children in his compound: “There were maybe 150 people in my compound. They did not take any man but abducted four women that afternoon, including one from my compound with her three children. We have no idea where they are.”

In October, Nuba community leaders said, rebels raped a 26-year-old female Nuba student in Goli, 30 kilometers west of Yei.

Human Rights Watch also heard from credible sources that in late September, rebel fighters abducted three women in Ombassi, 20 kilometers from Yei. Two are still missing but one escaped after three weeks with the rebels and was then detained for by police in Yei for three days in mid-October for questioning.

Sources who were told of the rapes said that women and girls raped in rebel areas were apparently unable, or too fearful of both sides, to cross lines to get medical care in Yei, though no such care is available outside the town. Many health facilities in rebel-controlled areas, including those that could have provided emergency post-rape care, were closed because of the lack of security or have been looted or otherwise vandalized.

Abuses of Sudanese Refugees

Refugees who fled from conflict in the Nuba mountains area of Southern Kordofan state in Sudan have been in the Yei area since 2011. Church and aid workers said that, following the increase in tensions in the Yei area, local people accused the Nuba refugees of taking up weapons and supporting the South Sudan government.

In August 2016, rebels ambushed a convoy of the UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, carrying 15 metric tons of food destined for the Lasu refugee camp, 46 kilometers southwest of Yei, which has about 2,000 mostly Nuba refugees and 8,000 Congolese refugees. In August and September, witnesses said that dozens of rebels entered the camp, wearing a mixture of civilian clothes and military fatigues, and looted the premises, including the clinic.

Aid groups have not provided any food to the camp residents since June 2016 due to lack of security, and the camp has since disbanded, with refugees fleeing to the bush and the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Arbitrary Restrictions on Freedom of Movement by Both Sides

In armed conflict, civilian movement may be restricted on security grounds or for imperative military reasons. However, some restrictions may also be arbitrary, and in some of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch the restrictions by both government and rebel forces appear to have been arbitrary. For example, in some cases, both SPLA forces and IO forces have stopped civilians in such a way as to unjustifiably obstruct access to health care and food.

Human Rights Watch was told that the Yei River state governor, David Lokonga, had publicly instructed civilians not to move outside the city limits. Researchers found a widespread perception by local civilians that the army would arrest or shoot at them if they traveled beyond two or three kilometers from the center of town.

Six women independently told Human Rights Watch that soldiers had chased them or their family members away when they tried to gather in areas around Yei, forcing them back into town.

In two cases, people were stopped by soldiers at checkpoints while trying to enter Yei for medical care. Soldiers beat one man in September when he tried to come into town for brucellosis medicines.

Fear of arrests and harassment at army checkpoints has led local civilians to use bush roads to get in and out of town. In one case in October, a pregnant woman from a nearby village delivered in the bush as she tried to get to the Yei Civil Hospital. Service providers told Human Rights Watch that when she finally reached the hospital, two days later, the baby had died.

Some of the government forces’ restrictions may also be discriminatory. Researchers visiting Yei mid-October saw hundreds of Dinka civilians leaving town for Juba in army trucks, assisted by SPLA soldiers. Civilians from Yei told researchers that people from the Dinka ethnic group were the only ones allowed to travel with the army convoys.

The rebels have also stopped civilians from moving freely into Yei. In the village of Goli, 30 kilometers west, rebels have prevented roughly 300 students from leaving the compound of their school since late September. The only remaining doctor of the Yei Harvester’s Hospital for Women and Children is also stranded in Goli, leaving the hospital unable to provide medical care to women during childbirth.

Rebels have also prevented civilians from returning to Yei with food, accusing those who do of feeding the Dinka. A 29-year-old woman told Human Rights Watch that rebel fighters called her “the wife of Dinka … [who wants to] feed the soldiers in Yei” and stopped her in September while she was bringing sweet potatoes from her farm in Lupapa, two miles out of town, back to Yei. Another 23-year-old business woman said rebel fighters stopped her from bringing food into Yei from nearby Sokah.

Both the general lack of security and arbitrary restrictions on movement by fighters on both sides have meant that government and church officials, health workers, and members of aid groups have been unable to reach some victims of abuse who live in areas under rebel control.