The attacks in Atlanta, killing six women of Asian descent, brought a sense of outrage, fear and sadness. It reminded me of the spikes in violence against the Indian community in New Jersey in the late 1980s.

In July 1987, a hate group called Dotbusters – referring to the bindi traditionally worn by Hindu women on their forehead - sent a handwritten letter to the local newspaper, spewing their hatred against the Indian population. The newspaper published it:

"I'm writing about your article…about the abuse of Indian People…I hate them, if you had to live near them you would also… We will go to any extreme to get Indians to move out of Jersey City. If I'm walking down the street and I see a Hindu and the setting is right, I will hit him or her.”

Storefronts owned by Asians were vandalized. An Indian man was beaten to death in Hoboken. Another was beaten unconscious by three young men with baseball bats on a busy street corner. One of the young people reportedly yelled, "There's a dothead! Let's get him!"

People in the Indian community were gripped with fear, as many Asian-Americans are today.

I was 12 at the time, and one of the few brown kids in my school. I grew up in a traditional family: my mother wore a sari every day, we regularly went to the temple, we greeted every adult as “aunty” and “uncle” – a sign of respect in Indian culture – and celebrated major Indian holidays within our close-knit community.

Instead of getting a hot lunch at school like many of my classmates, I often had a lunchbox with rotis and vegetable curry. I can remember kids mocking me, “Why aren’t you wearing a red dot on your forehead like your mother?” or making fun of India’s sacred cows. More than once strangers shouted at my family, “Go back to your country!” Yet I was born in the United States, and my parents were already US citizens.

I can remember attacks on Sikhs and Muslims in the days after 9/11. In one case, the man who killed a Sikh gas station owner in Arizona told his friends that he was “going to go out and shoot some towelheads.” Muslim friends told me about being profiled by police as they walked down the street, looking over their shoulder in constant fear.

Fast forward 20 years, I ask myself: Are things much different now?

Sadly, not much seems to have changed. Just a couple of years ago, a police officer made a racist comment to my mother without self-awareness or regret. Former President Donald Trump’s reckless rhetoric over the past four years has created a safe space for people to voice their anger and hatred against minorities, normalizing bigotry.

President Joe Biden was quick to condemn the “skyrocketing” of hate crimes against people of Asian descent – some 4,000 incidents documented by one organization alone – since the coronavirus pandemic began more than a year ago. These include an 84-year-old Thai immigrant in San Francisco who died after being violently slammed to the ground during his regular morning walk and an 89-year-old Chinese woman was set on fire in Brooklyn.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. famously said “[i]n the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.” During his visit to King’s hometown of Atlanta together with Vice President Kamala Harris, Biden shared similar sentiments when he said, "Our silence is complicity. We cannot be complicit. We have to speak out. We have to act.”

The federal government as well as state and local agencies need to do more to prevent discrimination, bullying, harassment and hate crimes against people of Asian descent, going beyond what was outlined in President Biden’s January 2021 memo on this issue. Expanding data collection and public reporting on hate incidents against Asian-Americans is important, but more needs to be done to investigate and hold accountable those who commit such crimes. Indeed, the New York Times recently reported that many attacks against people of Asian descent in New York City have either not led to arrests or have not been charged. We should also ensure that schools promote tolerance and address prejudice and bias.

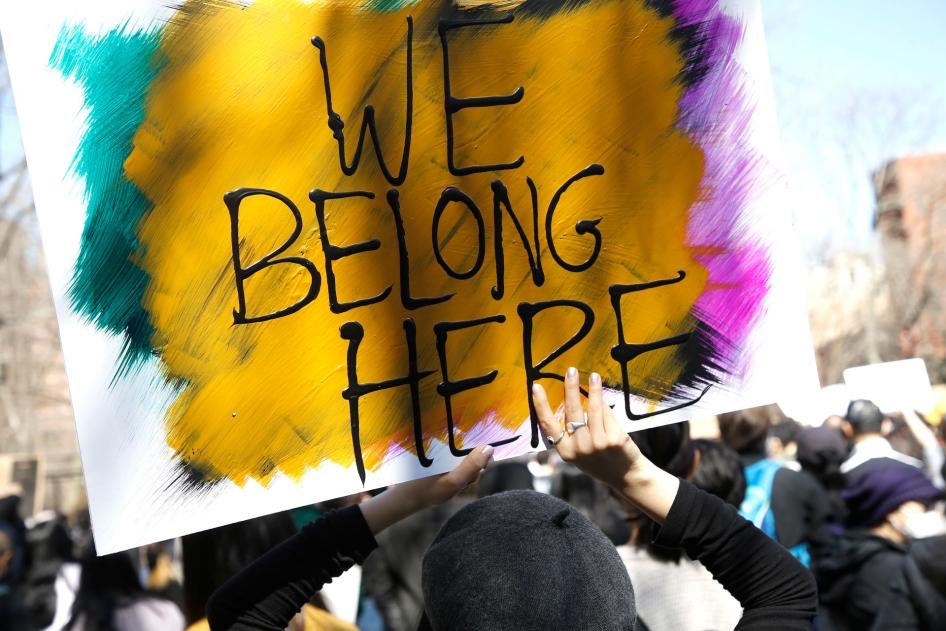

It’s not up to the government alone to stand up against hate crimes. We need a culture shift. Everyone should do their part to call out acts of hate and bigotry. Those concerned about anti-Asian discrimination need to join together with other national and local movements such as Black Lives Matter and disability rights activists, working in solidarity for equality and dignity. We also need to elect more diverse policymakers and leaders who represent our views and experiences.

I watched with pride and hope as the first woman of Indian descent was sworn in as vice president of the United States just a couple of months ago. As Vice President Harris said on inauguration day, “Even in dark times, we not only dream, we do. We not only see what has been, we see what can be.” Achieving real progress in the fight for racial equality is one of the greatest challenges facing this administration. Joe Uncle and Kamala Aunty, we are counting on you to take action.