The world might never have seen a video of this had an ISIS member not walked into a shop in the Syrian town of Tal Abyad in 2014 and left his computer for repairs. A worker there secretly copied the video and gave it to a Syrian news website, which posted it on June 26, 2014. The shop worker, with whom I later spoke, said he wanted to expose ISIS’ crimes.1

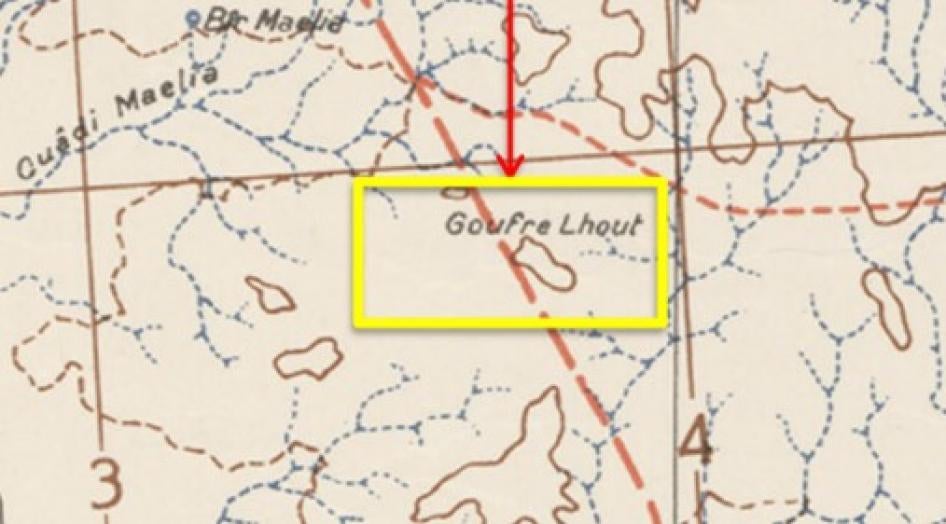

The video sparked a lengthy investigation by Human Rights Watch, one that had us scouring through satellite imagery and geological maps, viewing obscure videos from the war, and chasing down leads in Syria, Turkey, and France. We wanted to learn what happened at the gorge known as al-Hota, located 85 km north of Raqqa city.

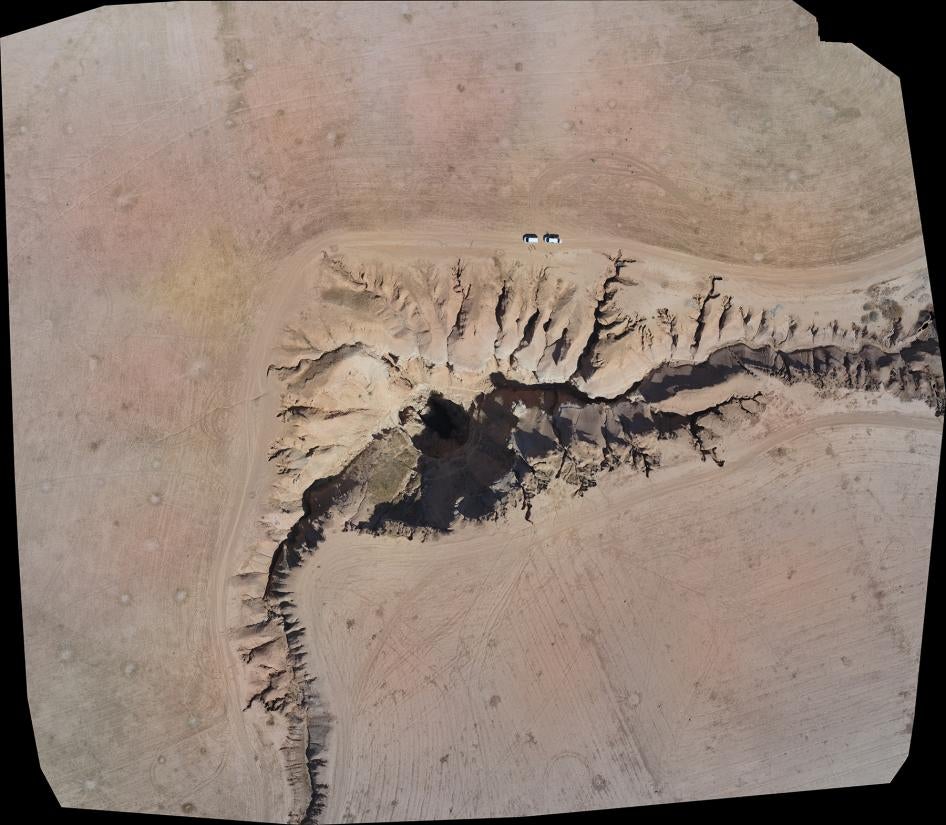

Eventually, in late 2017, after ISIS was forced out from the area, Human Rights Watch visited the site to inspect the gorge and to speak with people who lived nearby. One year after that, I returned with our director of geospatial analysis, Josh Lyons, and a drone to capture the first, gruesome images of what lay below the cliffs where these awful crimes took place.

ISIS abducted and detained thousands of people when they held swaths of territory in Syria between 2013 and 2019, many of whom had been executed or remain missing. The effort to identify these people and to locate their remains will last many years, as documented by Human Rights Watch in our recent report Kidnapped by ISIS: Failure to Uncover the Fate of Syria’s Missing. The effort to deliver justice for these extensive crimes is needed to promote a more stable Syria.

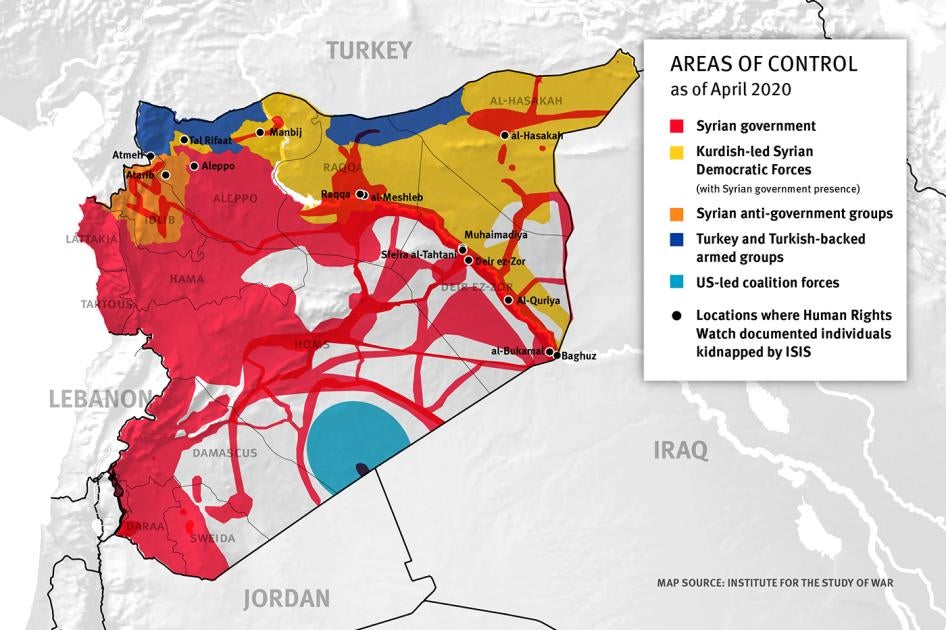

The bodies in al-Hota may provide some answers. The authorities who control the area should help them get it. As of February 2020, Raqqa city was controlled by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, while Suluk, a town in northern Raqqa governorate close to al-Hota, is controlled by the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army, as is the al-Hota gorge.2

Al-Hota: From Nature Site to Mass Grave

According to local residents, the al-Hota gorge once offered a pleasant escape from the dry plains north of Raqqa – a place for family picnics.

“Wild flowers would grow in the spring and families would gather between the crevasses for shade and cool air,” recalled Zakaria, a man who lived in the area.3 Pigeons built nests in the crevasses and flew around the sinkhole, he said.

The deep pit enchanted people from the area but also induced fear. No one knew its depth and locals spoke of an imaginary feminine creature – al-Sa`lawah in Arabic – that ate anyone who dared to climb down.4

When the Syrian conflict began in March 2011, the stories about al-Hota as a dumping ground for bodies began to spread. The first reported case came in September 2012, after an extremist Islamist armed group called the al-Qadsiya Brigade, headed by a local man named Faysal al-Ballo,5 together with other anti-government armed groups, seized a government-held checkpoint known as Bir `Asheq on the road between Tal Abyad and Suluk.6 Video taken after the fighting, recorded by someone who identified himself as from the “Media Office of the Qadsiyya Brigade,” shows at least 16 corpses of soldiers lying near the checkpoint.7 In a Facebook post dated September 19, 2012, two days after the fighting, the “Qadsiyya Brigade – North Raqqa” announced the deaths of 19 soldiers and the capture of 11 others.8 A local resident, Feras, said he heard that the eleven soldiers were executed after the fighting but he did not know anyone who saw the bodies and Human Rights Watch was not able to verify this claim.9

Two other local residents said that al-Qadsiyya Brigade fighters told them about dumping soldiers’ bodies into al-Hota.10 Neither person witnessed this nor saw bodies at the gorge. One of them said that groups with takfiri ideology, which encourages violent acts in response to apostasy, such as al-Qadsiyya Brigade, threw bodies into al-Hota when they considered them apostates who should not be buried with Muslims.11 A local journalist interviewed an area resident who said that he had climbed into al-Hota with three others on the evening when the soldiers were dumped there and they managed to retrieve two of the bodies that had gotten stuck on ledges, and give them proper burials.12 I interviewed the journalist but was not able to find his source.

In addition to killing government soldiers, locals said al-Qadisyya Brigade also killed civilians whom it accused of collaborating with the Syrian government. One local resident said he had heard about two people from the small village of Kherbet al-Faras, near Tal Abyad, – Ahmad (early 30s) and Nizar (age unknown) – whom the brigade had killed and dumped in al-Hota because they were allegedly Isma`ilis, a Muslim religious minority, and collaborators with the Syrian government.13

According to another local resident, al-Qadsiyya Brigade dissolved shortly after other armed groups took Tal Abyad around September 2012 and its fighters joined those other groups, mostly al-Nusra Front and later ISIS.14 A distant relative of Faysal al-Ballo confirmed that his relative was in charge of al-Qadsiyya, and that he subsequently joined Nusra Front, and later ISIS.15 The last post on the Facebook page of “Qadsiyya Brigade – North Raqqa” dates from September 17, 2012.16

One resident of a village near al-Hota believed al-Qadsiyya Brigade was not the only anti-government armed group to have thrown bodies into the gorge. 17 He said he heard that Ansar al-Haqq, a local brigade considered part of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), had killed a solider in Tal Abyad and disposed of his body in al-Hota, but he did not see this himself and could not provide details. We were not able to obtain more information about this alleged death.

March 2013 – Armed Groups Take Control of Raqqa; Executions and Killings of Government Forces

In March 2013, armed groups opposed to the Syrian government seized Raqqa city. The attack was led by several groups, ranging from extremist Islamist groups, including Ahrar al-Sham, al-Nusra Front, and the Hudhayfah ibn al-Yaman Brigade, to groups affiliated with the Free Syrian Army.18 After the city’s fall, the attackers killed an undetermined number of government soldiers and security officers, some of them reportedly executed after surrendering.19 What ultimately happened to their bodies remains unknown.

One month later, on April 18, a local media activist posted two videos to Facebook that showed him standing at al-Hota proclaiming that “hundreds of bodies” of government soldiers and members of the security services – who he called “Bashar al-Assad’s militias” – were dumped there.20 The two videos did not show any bodies or indicate which armed groups had allegedly dumped them there. The activist did not say if the bodies were of those killed in fighting, but the timing of the videos suggest that he was referring to government soldiers and security officers who were killed in Raqqa city in March of that year.

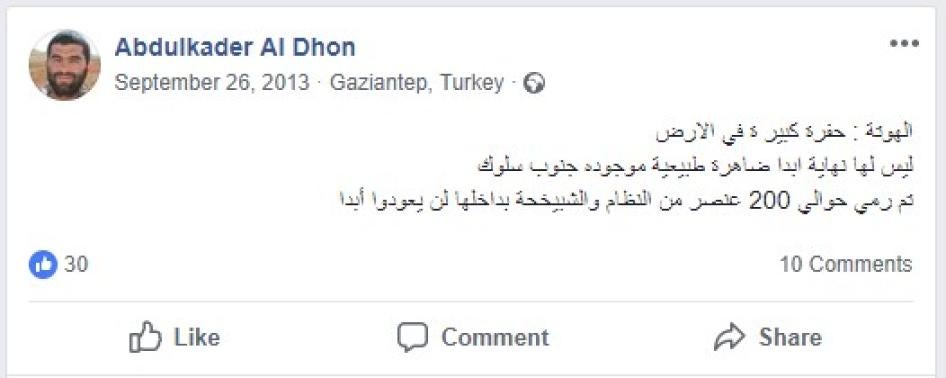

In September 2013, a Syrian rights activist who worked with international journalists and organizations and visited Raqqa on a number of occasions, Abdul Kader al-Dhon, posted on Facebook that the bodies of an estimated 200 government soldiers and shabbiha (what anti-government activists call pro-government paramilitaries) had been thrown into al-Hota. Al-Dhon did not provide details or specify the source of his information. He himself would be kidnapped in March 2015 in northern Syria, most likely by ISIS, and his fate remains unknown.

ISIS Controls Raqqa Governorate, Begins to Use al-Hota

On April 8, 2013, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of ISIS at the time, announced that al-Nusra Front had been established, financed, and supported by the Islamic State of Iraq, and that the two groups were merging under the name Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS). While Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, the head of al-Nusra, rejected the creation of the group, many fighters from al-Nusra switched sides and joined ISIS, which suddenly found itself with a strong presence in Raqqa.21

Over the coming months, ISIS consolidated its control over the city and fought groups that stood in its way. In the process, ISIS abducted, disappeared, tortured, and executed scores of Syrian activists and journalists, fighters opposed to ISIS, and international journalists and humanitarians.22 Many families of these victims received no information about the fate of their loved ones.23

By January 2014, ISIS had solidified its control over Raqqa and imposed its authoritarian style of governance on the city and surrounding countryside. To enforce control, the group carried out executions in public squares in Raqqa and neighboring towns.24 In some cases, ISIS would leave the bodies on display before taking them away, but the destination stayed unknown. 25

“When ISIS took over, executions increased,” a local resident who remained in the city explained. “Some bodies would be crucified after being executed. They executed soldiers of the regime, but also other people who opposed them.”26

Raqqa residents began to suspect that ISIS was throwing some of the bodies into al-Hota but people feared approaching the site. Munir, a local activist who was arrested by ISIS in January 2014 because they suspected him of running a critical Facebook page, said that one of his interrogators threatened him with a fate in al-Hota. “If you don’t collaborate, we will take you to al-Hota,” he said he was told.27

Another Raqqa resident, Hassan, whose aunt was detained by ISIS in 2014 because she refused to wear the niqab, said that ISIS mentioned al-Hota when he went to ask about her. “Forget about her, we threw her into al-Hota,” Hassan said an ISIS member told him.28 Hassan did not know at the time if the information was truthful or meant to stop him from asking questions.

Around that time, the first video of ISIS throwing bodies into al-Hota appeared. On June 26, 2014, the Syrian anti-government, anti-ISIS news site Masarrat, now closed, posted a video of two men being thrown into the pit after they had allegedly been executed in Suluk. The person who provided the footage to Masarrat told us he secretly copied the video in mid-2014 from the laptop of an ISIS member who had left the computer in a repair shop in Tal Abyad.29 The Masarrat video was actually a composite of two videos obtained from the device. One showed ISIS executing three men on the main roundabout of Suluk, and the other showed men throwing two bodies into al-Hota. The clothes of two of the men being executed in Suluk matched those of the two bodies being thrown into the gorge. The date of the executions is unknown.

While the video established that ISIS was using al-Hota to dump bodies, the frequency and scale remained unknown. Local residents in the area said they would regularly see ISIS driving trucks to the site but that they did not dare to approach the area. “If you asked questions about it, you risked ending up there yourself,” one of them said.30

Human Rights Watch spoke separately with three people who said that they had been to al-Hota during the time of ISIS control. Each of them said they had seen bodies scattered along the gorge’s edge.

One man said he had gone to collect desert truffles that grow in the area when he saw a body stuck on a protruding ledge.31 Another man who worked in the area at the time said he saw a family pull the body of their dead relative from the gorge.32 A third man said he went to al-Hota to look for his cousin, who had been detained and executed by ISIS. At the site, he saw a number of bodies around the pit’s edge, many of them in military uniform, but none of them were his cousin.33

The man who was looking for truffles said he went to al-Hota around March 2015 and saw an unidentified body stuck on a ledge. “This was a dumping area for bodies from all over,” he said. “They [ISIS] brought them in from Raqqa, Deir al-Zor —nobody knows how many bodies were there.”34

The man who worked at the electrical substation said that during the summer of 2014 a family came to al-Hota to look for a relative whom ISIS had detained because he was smuggling food to besieged government troops. They had heard that ISIS had killed the man and thrown his body into al-Hota. The family retrieved a body that was badly burnt, he said.35

The man who went looking for his cousin, Zacharia, said that he went to al-Hota three times in the latter months of 2014. He explained one of the visits:

I was trying to see if I can find the body of my cousin Ahmad, who had been taken and killed by ISIS. It was around midday as no one usually was there around that time. We were three people on a motorbike, and I would just jump off the motorbike and walk to the edge so that no one notices anything parked near the gorge. I saw many bodies. They were lying in different stages of decomposition. I saw only males, including two who looked like teenagers. But I did not find Ahmad’s body. I did not recognize anyone. Many were wearing army fatigues. I believe they were regime soldiers killed when ISIS took control of nearby bases.36

Zacharia said his family later received information that his cousin had been buried in a different area.

Two ISIS defectors who spoke to foreign journalists said that they had witnessed the disposal of bodies in al-Hota. Journalist Robert Worth interviewed a man identified as Abu Abdullah, a 22-year old who said that he had taken part in the conquest of Raqqa and later served in ISIS’s intelligence wing.37 Abu Abdullah said that in late summer 2014 he was assigned to provide security for a convoy of dump trucks that carried bodies to al-Hota. He said the bodies were of members of al-Sha`aitat tribe — a tribe in eastern Syria that had opposed ISIS and had many of its members executed.

Abu Abdullah said the trucks arrived at the edge of al-Hota, tilted their beds back, and dumped dozens of corpses into the ravine, including of women and children. “There were dozens of them,” he told Worth. “Many had been shot in the head. The little bodies rolled down the slope of the gorge, shedding bloody scarves and shoes as they went, like garbage flooding into a bin.” Worth wrote that Abu Abdullah showed him a “haunting video” of al-Hota that he said he had recorded in the spring of 2015:

In the golden afternoon light, the gorge looks a little like part of the Grand Canyon, with layered sedimentary rocks in varying tones of rusty brown and umber. The camera pans upwards, showing the fading blue sky, the silhouette of a rock formation, and then down towards the black hole at the bottom. You can see corpses strewn at various places on the way down. Some are very close to the camera, and some have rolled down towards the pit.38

I tried to locate and interview these witnesses without success, so I cannot verify their claims.

The other ISIS defector, who went by the name Abu Maria, spoke with the French journalists Thomas Dandois and Francois-Xavier Trégan. He said that he had been ordered to execute a young Syrian journalist whom he did not identify who had worked with the FSA. The journalist’s body was thrown into al-Hota, he said.39 Abu Maria also claimed that while disposing of the body, he saw the dead bodies of a man and woman lying there.40

A Syrian journalist, who wrote under the pseudonym Ahmed Ibrahim for security reasons, interviewed a man who said that he had descended into al-Hota on July 12, 2014 to extract the body of his brother, whom ISIS had thrown there.41 The man told Ibrahim that his brother had joined ISIS but clashed with his commander after accusing him of stealing Syrian antiquities. The dispute escalated and the commander reportedly sentenced the man’s brother to death and had him thrown into al-Hota. The man said he followed an ISIS convoy to al-Hota and, after they departed, he climbed down and pulled his brother’s body from a ledge. His brother had been wounded but apparently survived, though he suffered a permanent disability. Human Rights Watch tried to interview the man in June 2015 after he had reportedly entered a refugee camp in southern Turkey, but we were not allowed to enter the camp. I interviewed the journalist, Ibrahim, but he said he had lost contact with his source.42

Al-Hota is not the only natural formation that ISIS used as a mass grave. A sinkhole near Mosul, Iraq, was used to dump possibly hundreds of bodies.43 Multiple witnesses told us that ISIS had disposed of those it had killed, including members of Iraqi security forces, in al-Khafsa, about eight kilometers south of western Mosul. Local residents said that before pulling out of the area in mid-February 2017, ISIS booby-trapped the area with improvised explosives.

Visiting al-Hota

In late May 2015, the Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG) and the Free Syrian Army (FSA) launched an offensive against ISIS in the area around al-Hota. By June 14, 2015, YPG forces had captured the town of Suluk and several surrounding villages.44

In October 2015, a local journalist working for Voice of America visited al-Hota.45 Filming from the edge of the sinkhole, a soldier from the YPG tells the journalist that they could still see two bodies lying on the rim.

At that stage, we began planning to visit the site. Preparations took longer than expected as ISIS remained a threat and we needed official permissions that took months to obtain.46

Finally, in July 2017, I entered northeast Syria with a colleague and headed towards al-Hota. One concern was the possible presence of landmines and improvised explosive devices. Four months before, in al-Khafsa, the sinkhole that ISIS had used to dump bodies in Iraq, a booby trap had killed a journalist and at least three Iraqi security forces.47

We also worried about conditions at the site, and whether any evidence of war crimes had been preserved. Media reports said that local residents had reported ISIS dumping fuel into the gorge and setting it on fire to hide the smell of bodies.48 Colleagues who had visited al-Khafsa three months before our visit to al-Hota reported that ISIS had filled that sinkhole with earth between March and June 2015.49

We drove to al-Hota with officials from the Raqqa Local Council, the civilian body that the Syrian Democratic Forces – Kurdish-led military forces composed primarily of the People’s Protection Units and at the time backed by the United States – had set up to administer areas in the Raqqa governorate. They had also heard about al-Hota and were curious to visit.

We arrived as the sun had begun to set. The area was serene and beautiful, where families had once picnicked, but we knew that we were possibly standing before an open mass grave. We approached the rim and one of our fears was immediately confirmed: the paths from the edge were littered with landmines and unexploded ordinance. We could not walk further and peer into the pit.

From our position, it was impossible to see the bottom of the gorge or to determine whether any bodies were along the lower ledges. At least the site seemed to be intact; ISIS had apparently not tried to conceal its crimes.

We promptly began planning to visit again. Descending into al-Hota was clearly difficult and dangerous, but a camera-equipped drone might reveal what lay below.

A few months earlier, in May 2017, Human Rights Watch had used a drone for the first time to conduct research, documenting the health impact of the garbage crisis in Lebanon.50 That mission had proven successful but the conditions were favorable: an accessible area and flat terrain. Flying a drone into al-Hota would require obtaining permissions to bring the equipment into northeast Syria at a time when ISIS had been using drones to launch attacks in Syria and Iraq. Once we got to al-Hota, we would have to navigate the drone into the pit.

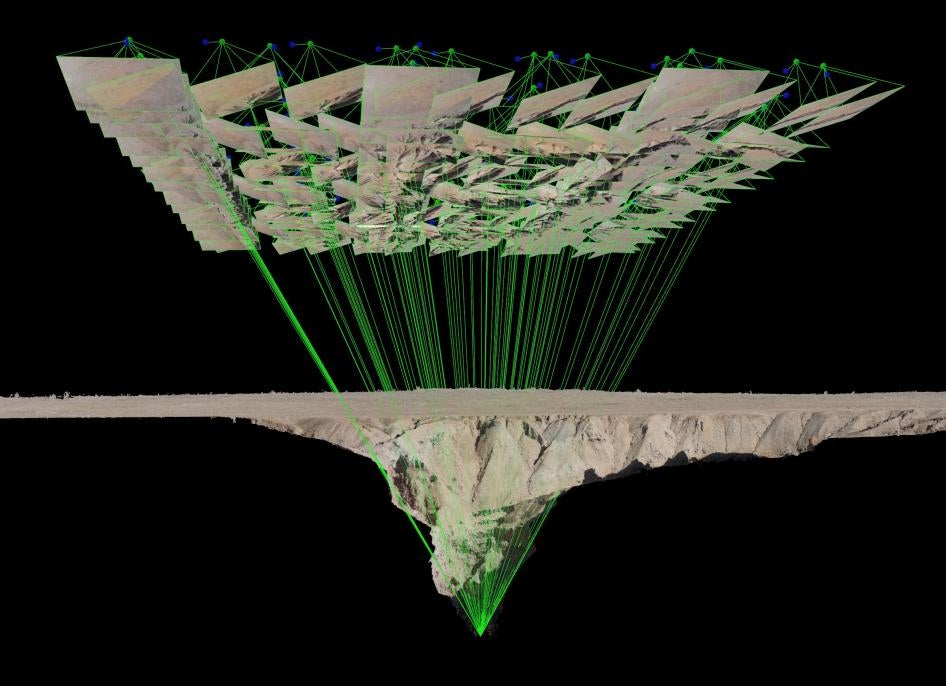

It took one year to obtain approvals and in September 2018 we made our way back to al-Hota, this time with our geospatial expert, who had been monitoring al-Hota since 2014. He brought two Parrot ANAFI drones with high-resolution video cameras.

Local officials did not accompany us to the site this time, but they did send three security guards from the Kurdish security forces, Asayish. We prefer to operate independently, without escort, but we accepted the escort because we were going to an isolated area with a possible ISIS presence and boobytraps. We did not think that the Asayish presence would influence the drone flight or our findings.

The site had not changed much since our visit one year before, though some of the land mines apparently had been removed, or perhaps washed down by rain. No fences had been erected to protect people from the dangers or to preserve the site for exhumations. With some paths clear, we walked through the crevasses to a secure ledge from where we could launch the drone.

We knew it was going to be technically challenging to operate the drone inside the gorge, but it proved to be even more difficult than we expected. First, as the drone was hovering above the sinkhole, dozens of birds inside flew suddenly into the air and almost crashed into it. Then, as the drone descended out of sight, an alarm sounded as it quickly lost GPS connection and grew unstable in flight and at risk of crashing. After a few stressful moments however, the drone stabilized itself automatically as it reached the bottom, allowing us to concentrate on the live video feed it was sending of what lay below.

At first, we saw only a black pit. Then, slowly, the bottom of the gorge came into view; it was filled with dark, murky water. The reading on the Parrot ANAFI drone registered a depth of about 50 meters. Then we saw bodies floating on the water – six in total, floating in different positions, all of them face down. Stefan Schmitt, a forensic expert who examined images of the bodies later told us the state of decomposition suggested they had been disposed of within a few weeks of our visit.51

To discover bodies recently thrown into al-Hota, over three years after ISIS left the area, raised a host of questions. Who were these people, how did they die, and who threw their bodies into the gorge?

Our security escorts said they did not know who they were. They might have been the victims of “revenge killings between local residents,” one Asayish officer said.52 We were unable to obtain any additional information about these people, and the circumstances of their deaths remain unknown.

And what of the other people whom ISIS had apparently thrown into the gorge? Were more human remains concealed beneath the water?

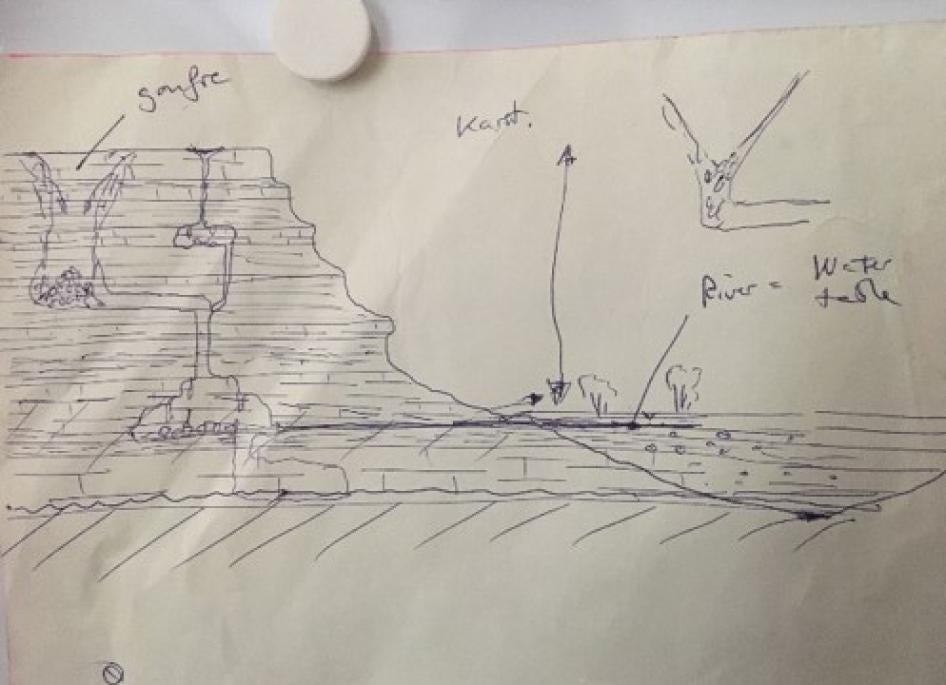

Back home, we examined the drone video to assess the depth and geological structure of the gorge. We constructed a 3D topographic model of al-Hota from the drone imagery and collected Soviet geological maps from the 1960s and 1970s. Then we met with a Swiss geologist, Antoine de Haller, and showed him the videos and geological data. 53

He told us it was impossible to say exactly how deep al-Hota was based on the Soviet maps and our drone imagery alone, but he believed the surface of the water at the time of our visit may not represent the bottom, and that the cave could descend even deeper as part of a larger system of caves in limestone. In other words, more human remains could lie below.

The Way Forward

Many questions about al-Hota remain. But we know that bodies were thrown into the gorge and that further investigation is required.

On October 9, 2019, the Turkish Armed Forces and the Syrian National Army, a non-state armed group backed by Turkey, invaded territory in northeast Syria that was controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces.54 The incursion occurred after the United States, the Kurdish-led forces’ main ally, announced its withdrawal.55

Four days later, the Syrian government and Syrian Democratic Council, the civilian body leading Kurdish-led forces in northeast Syria, reached an agreement brokered by Russia to allow Syrian government forces into areas held by the SDF to support them against the Turkish incursion.56 An agreement between President Erdogan of Turkey and President Putin of Russia on October 22 allowed Turkey to retain areas it had taken and required the Kurdish-led forces to withdraw. 57 It also cemented the Syrian government’s presence in other areas in the Northeast.

At the time of writing, Turkish Armed Forces and the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army had taken control of the area between Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ayn and cut off part of the international M4 highway that runs between southeast Turkey and northeast Syria.58 Part of that territory includes Suluk, and the area where al-Hota is located.

Whichever authority establishes control of the area is obliged to protect and preserve the site, and to facilitate the collection of evidence that would help hold ISIS members accountable for the crimes they committed, as well as those who dumped bodies in al-Hota after ISIS left. First, local authorities, with the help of their international allies, should treat al-Hota as a crime scene, and secure and cordon off the site so potential evidence is not destroyed, as well as to stop any further dumping of bodies into the gorge. Second, the gorge should be drained to allow deminers to clear the site. Third, trained and equipped forensic experts should descend into the gorge, remove those bodies and to begin the painstaking work of documentation and exhumation.

At the same time, the authorities in control of the site should communicate with and support families with relatives who went missing or were killed. They should update families about what is happening at al-Hota and how the authorities are working to promote justice for grave crimes, whether during or after ISIS’s rule. This is a part of the de facto authority’s obligation under international law to take all feasible measures to account for persons reported missing as a result of armed conflict and provide their family members with information it has on their fate.59 The obligation is predicated on the right of the families of those missing to know the fate of their loved ones, and the concurrent obligation on states and de-facto authorities to provide that information.

Efforts to exhume al-Hota should form part of a larger effort to determine the fate of thousands of people who have disappeared in Syria since the conflict began in 2011. Relatives of some detainees who went missing at the hands of ISIS launched several campaigns to seek the help of the US-led coalition against ISIS, the Kurdish authorities and, in some cases, the Syrian government, to determine these people’s fate, but they never received responses.60

While we don’t know whose bodies are in al-Hota, how many or how all of them got there, discovering what happened at al-Hota – and the other mass graves in northeast Syria – is an essential step to determine the fates of the thousands of people who were captured and executed by ISIS, and to hold ISIS members accountable for the crimes they have committed.

Under international law, the mutilation of dead bodies is prohibited, and all parties to the conflict must take all possible measures to prevent them from being despoiled. By throwing these bodies into al-Hota, ISIS may well have violated the law. Dedicating resources to preserving al-Hota and collecting evidence will also support the investigation into other violations committed by ISIS, including extrajudicial execution of civilians or fighters who surrendered which constitute serious violations of the laws of war, and when committed with criminal intent, are war crimes.

Al-Hota, once a place of beauty and tranquility, has become a symbol of horror and death. Families who lost loved ones, some of whom were thrown into al-Hota, deserve answers. Families across Syria, seeking closure to the violence that has torn their country apart, deserve the same.

Acknowledgments

This report was written primarily by Nadim Houry, former director of the Terrorism and Counterterrorism Division at Human Rights Watch, together with Sara Kayyali, Syria researcher, and Josh Lyons, director of geospatial analysis, who also conducted research and guided our use of the drone. Associate program director Fred Abrahams managed the project.

The report was edited by Stephen Northfield, digital director, Joe Stork, deputy director in the Middle East and North Africa Division, and Clive Baldwin, senior legal advisor.

The report was prepared for publication by an associate in the Middle East and North Africa Division; Travis Carr, photography and publications coordinator; Chandler Spaid, multimedia assistant editor; and designed for the web by Christina Rutherford, senior digital manager.

Human Rights Watch thanks the company Parrot for donating the Parrot ANAFI drones that we used for this report.

Footnotes

1 Human Rights Watch phone interview with Abboud, Raqqa governorate, October 19, 2018. A copy of the video can be found https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iOW-aMUYNNs (accessed November 5, 2019). The names of this interviewee and others have been changed to protect them from possible retaliation.

2 Human Right Watch interview with residents of Suluk, December 2019.

3 Human Rights watch interview with Zacharia, Suluk, September 23, 2018.

4 Human Rights Watch interview with Munir, Ain Issa, September 24, 2018. Also see Ahmed Ibrahim, Al-Jumhuriya, “Da'esh and the Gorge,” September 11, 2015, https://www.aljumhuriya.net/ar/content/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%87%D9%88%D8%AA%D8%A9 (accessed February 20, 2020).

5 According to interviews with local area residents, al-Qadsiya Brigade, with its headquarters in al-Muhaysen, set up in the area around al-Hota in February 2012 and initially pledged allegiance to Ahrar al-Sham. The brigade and other groups aligned with the opposition Free Syrian Army took control of Suluk in summer 2012 and then tried to take the town of Tal Abyad. By September 2012, the brigade had declared its support for the al-Nusra Front; see also book by Maabad al-Hassoun: Raqqa and The Revolution: A Personal Testimony, p. 21.; Facebook group for Qadsiyya Brigade: https://www.facebook.com/%D9%83%D8%AA%D9%8A%D8%A8%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%...

6 Video of Bir Ashek checkpoint under attack available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=trcEqjqkCuY (video uploaded on September 25, 2012)

7 See (Graphic Content): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6e907M9seNQ&has_verified=1 (accessed November 5, 2019). HRW verified the video recording location (27km north of al Hota) and approximate date by matching the checkpoint in satellite imagery.

8 See https://www.facebook.com/%D9%83%D8%AA%D9%8A%D8%A8%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%... (accessed February 20, 2020).

9 Human Rights Watch interview with Feras, Suluk, September 23, 2018.

10 Human Rights Watch interview with Munir, Ain Issa, September 24, 2018; Human Rights Watch phone interview with Imad, Raqqa governorate, October 1, 2018. See also reporting by the Lebanese newspaper al-Akhbar about the disposal of bodies of government soldiers in al-Hota: https://www.al-akhbar.com/Syria/19097 (accessed November 5, 2019).

11 Human Rights Watch interview with Munir, Ain Issa, September 24, 2018.

12 Ahmed Ibrahim, Al-Jumhuriya, “Da'esh and the Gorge,” September 11, 2015, https://www.aljumhuriya.net/ar/content/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%87%D9%88%D8%AA%D8%A9 (accessed February 20, 2020). Takfiri ideology indicates when a Muslim declares another Muslim an apostate based on a set of actions or sayings.

13 Human Rights Watch interview with Feras, Suluk, September 23, 2018.

14 Maabad al-Hassoun, Al-Raqqa and the Revolution (only available in Arabic as an e-book), p. 21 https://www.raqqapost.com/29210/2017/11/07 (accessed February 20, 2020).

15 Human Rights Watch phone interview with Abboud, Raqqa governorate, October 19, 2018; Human Rights Watch interview with Munir, Ain Issa, September 23, 2018.

16 See: https://www.facebook.com/%D9%83%D8%AA%D9%8A%D8%A8%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%... (accessed February 20, 2020).

17 Human Rights Watch interview with Feras, Suluk, September 23, 2018.

18 For a structure of the groups, see https://www.joshualandis.com/blog/the-raqqa-story-rebel-structure-planni... (accessed February 20, 2020).

19 Ben Hubbard, Associated Press, “Captured Syrian city a test for rebel forces as they govern, kill captives,” March 10, 2013 https://web.archive.org/web/20130315004729/http://www.newser.com/article... (accessed February 20, 2020).

20 The two videos were posted on the YouTube channel and Facebook page of Raqqa U.M.C. (the Raqqa Unified Media Center). The YouTube Facebook accounts were later closed; HRW has preserved copies on file.

21 Naharnet, Al-Nusra Commits to al-Qaida, Deny Iraq Branch 'Merger', April 10, 2013, http://www.naharnet.com/stories/en/78961-al-nusra-commits-to-al-qaida-deny-iraq-branch-merger/ (accessed February 20, 2020).

22 See Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic* Rule of Terror: Living under ISIS in Syria, A/HRC/27/CRP.3, pp. 7-8. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/CoISyria/HRC_CRP_ISIS...

23 Human Rights Watch, Kidnapped by ISIS: Failure to Uncover the Fate of Syria’s Missing, February 2020, https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/02/11/kidnapped-isis/failure-uncover-fate-syrias-missing.

24 Ibid.

25 Human Rights Watch interview with residents of the area, September 2018.

26 Human Rights Watch interview with Munir, Ain Issa, September 24, 2018, Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmed Ibrahim, France, June 10, 2017.

27 Human Rights Watch interview with Munir, Ain Issa, September 24, 2018.

28 Human Rights Watch interview with Hassan, Raqqa, September 26, 2018.

29 Human Rights Watch phone interview with Abboud, Raqqa governorate, October 18, 2018. See also Ahmed Ibrahim, Al-Jumhuriya, “Da'esh and the Gorge,” September 11, 2015.

30 Human Rights Watch interview with Feras, Suluk, September 23, 2018.

31 Human Rights Watch interview with Syrian asylum-seeker, Akcakale, Turkey, June 25, 2015.

32 Human Rights Watch phone interview with Imad, Raqqa governorate October 1, 2018.

33 Human Rights Watch interview with Zacharia, Suluk, September 23, 2018.

34 Human Rights Watch interview with Syrian asylum-seeker, Akcakale, Turkey, June 25, 2015.

35 Human Rights Watch phone interview with Imad, Raqqa governorate, October 1, 2018.

36 Human Rights Watch interview with Zacharia, Suluk, September 23, 2018.

37 Robert F. Worth, “The reluctant jihadi: how one recruit lost faith in Isis,” The Guardian, April 12, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2016/apr/12/reluctant-jihadi-recruit-lo... (accessed February 20, 2020).

38 Ibid.

39 Tomas Dandois, Francais-Xavier Trégan, “Daesh, paroles de déserteurs,” p. 102.

40 Ibid, p. 57.

41 Ahmed Ibrahim, Al-Jumhuriya, “Da'esh and the Gorge,” September 11, 2015, https://www.aljumhuriya.net/ar/content/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%87%D9%88%D8%AA%D8%A9 (accessed February 20, 2020).

42 Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmed Ibrahim, France, June 10, 2017.

43 Iraq: ISIS Dumped Hundreds in Mass Grave, Human Rights Watch News Release, March 22, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/03/22/iraq-isis-dumped-hundreds-mass-grave.

44 See “We Had Nowhere Else to Go, Forced Displacement and Demolitions in Northern Syria,” Amnesty International report, October 2015. https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/MDE2425032015ENGLISH.PDF; and Pitarakis, Lefteris, and Bassem Mroue. “Thousands Flee Syria as Kurds Fight Islamic State” The Boston Globe, June 15, 2015, https://www.bostonglobe.com/news/world/2015/06/14/thousands-syrians-flee... (accessed February 20, 2020).

45 “VOA Visits Syrian Pit Where Islamic State Disposed of the Executed”, VOA News video, October 19, 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=3teI7RxTjSk&app=desktop, (accessed November 15, 2015).

46 In February 2016, ISIS led an attack and recaptured the area momentarily before losing it again to the YPG on March 2016. See Karouny, Mariam, and Seyhmus Cakan, “Islamic State Attacks Kurdish-Held Town on Turkish Border”, Reuters, February 27, 2016, uk.reuters.com/article/uk-mideast-crisis-syria-telabyad-idUKKCN0W00EQ (accessed February 20, 2020).

47 Iraq: ISIS Dumped Hundreds in Mass Grave, Human Rights Watch News Release, March 22, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/03/22/iraq-isis-dumped-hundreds-mass-grave.

48 Bashir al-Bakr, “al-Hota, ISIS grave in Raqqa”, December 15, 2017, https://www.alaraby.co.uk/opinion/2017/12/14/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%87%D9%88%D8... (accessed February 20, 2020).

49 Iraq: ISIS Dumped Hundreds in Mass Grave, Human Rights Watch News Release, March 22, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/03/22/iraq-isis-dumped-hundreds-mass-grave.

50 “Lebanon: Waste Crisis Posing Health Risks,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 1, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/12/01/lebanon-waste-crisis-posing-health-r....

51 Human Rights Watch interview with Stefan Schmitt, October 9, 2018.

52 Human Rights Watch interview with an Asayish officer, al-Hota, Syria, September 23, 2018.

53 Human Rights Watch interview with Antoine de Haller, January 6, 2019, Geneva, Switzerland.

54 McKernan, Bethan, et al. “Turkey Unleashes Airstrikes against Kurds in Northeast Syria”, The Guardian, October 9, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/09/turkey-launches-military-o... (accessed February 20, 2020).

55 Marcus, Jonathan “Trump Makes Way for Turkey Operation against Kurds in Syria”, BBC News, October 7, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-49956698?intlink_from_url=htt... (accessed February 20, 2020).

56 “Syria’s Army to Deploy along Turkey Border as Kurds Strike Deal”, Al Jazeera News, October 14, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/10/syrian-army-deploy-turkey-border-... (accessed February 20, 2020).

57 Full Text: Memorandum of Understanding between Turkey and Russian on Northern Syria, The Defense Post, October 22, 2019. https://thedefensepost.com/2019/10/22/russia-turkey-syria-mou/ (accessed February 20, 2020).

58 “8 days of Operation ‘Peace Spring’: Turkey controls 68 areas, ‘Ras al-Ain’ under siege, and 416 dead among the SDF, Turkish forces and Turkish-backed factions”, Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, October 17, 2019, http://www.syriahr.com/en/?p=144313 (accessed February 20, 2020).

59 See International Committee of the Red Cross, Customary International Law Database, Rule 117, Accounting for Missing Persons, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docs/v1_rul_rule117 (accessed September 1, 2019).

60 Human Rights Watch, Kidnapped by ISIS: Failure to Uncover the Fate of Syria’s Missing, February 2020, https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/02/11/kidnapped-isis/failure-uncover-fate-syrias-missing ; The campaigns are: ‘Where are the kidnapped by ISIS?’; The Coalition of Families of Kidnapped by ISIS; Al-Mafqoudin (The Missing); and the Kurdish-led group (unnamed).