On Wednesday, there was yet another tragedy off the Greek island of Lesbos, when a large Turkish fishing boat carrying some 300 people trying to reach Europe sank, causing at least seven to drown, including four children, with at least 34 still missing. The needless loss of life should be enough to outrage us all. But just as outrageous is the reality that months into Europe’s refugee crisis, Europe’s leaders still have not taken the steps necessary to help prevent such unnecessary tragedies, let alone adopt policies that could provide people fleeing war and repression with legal and safe alternatives to seek asylum in Western Europe.

Turkish smugglers taking advantage of those desperately fleeing the horrors of war in Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq promised the victims that the trip aboard a “yacht” would be safer than the more common trips in overloaded rubber dinghies. They then packed the 300 people like sardines on both decks of the aging fishing vessel.

Disaster unfolded as the boat hit rough seas and high winds at about 4 in the afternoon. Suddenly, the sheer weight of those packed on the upper deck caused it to collapse, crashing everyone down onto the lower deck. Spanish volunteer life guards, working on the beaches of Lesbos to bring in the boats safely, watched the tragedy unfold through their binoculars from a beachhead on the Greek island.

A Syrian man who survived told one of the doctors who treated the survivors that the collapse of the upper deck injured many people and created a large hole in the bottom of the boat, which began filling with water. The Turkish smuggler driving the boat called his fellow smugglers, and a speedboat came to evacuate him, its occupants firing several times in the air to warn off the panicking people on the boat. As it evacuated the skipper, the speedboat hit the fishing boat, causing it to sink almost immediately.

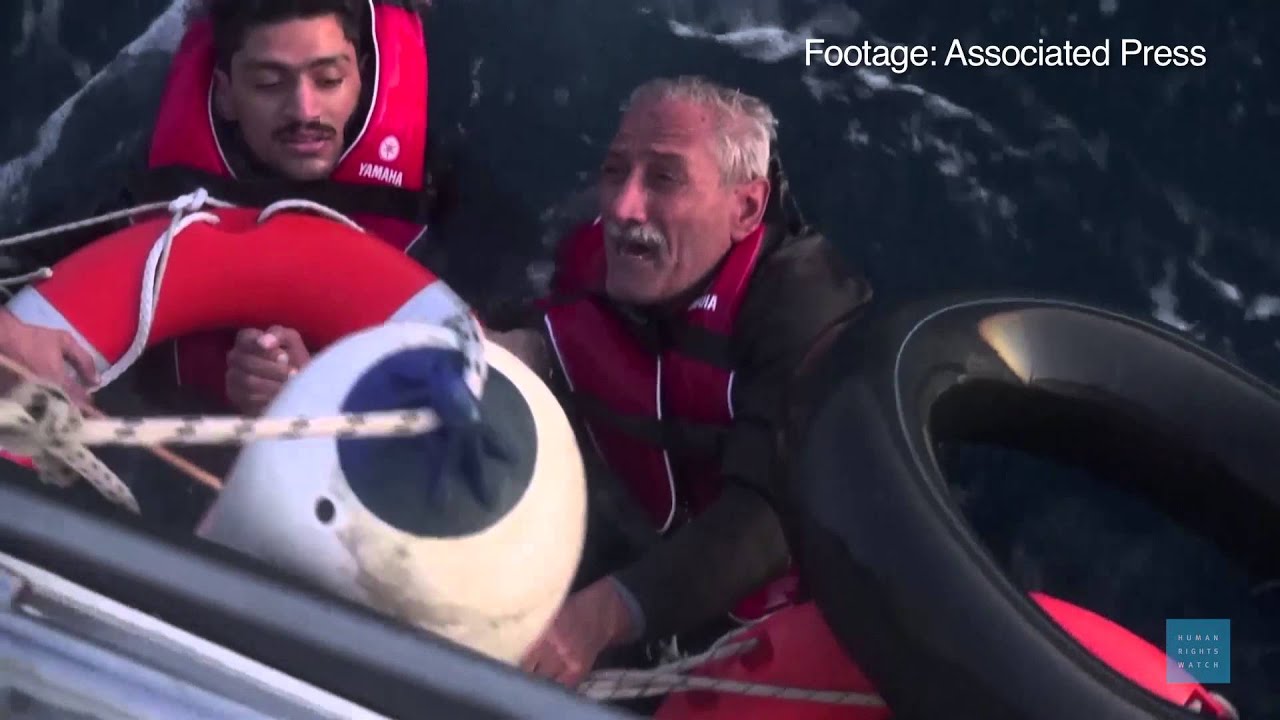

“Suddenly, we just saw hundreds of lifejackets in the sea,” Gerard, one of the Spanish volunteer lifeguards, told me over the phone. “We rushed down to get our jet skis, and we were in the water in minutes.”

For more than four hours, until long after nightfall, three Spanish lifeguards tried to rescue as many of the people in the water as they could, using only their jetskis in the rough water many kilometers offshore. They performed CPR on some right on their jetskis. Several local fishing boats also came to join the rescue efforts, pulling survivors out of the water until their decks were packed with shivering, traumatized survivors.

Both the Greek coast guard and boats under the coordination of FRONTEX, the EU’s external borders agency, joined the effort as well, but their large boats sitting high out of the water made it difficult to hoist survivors unto their decks in the rough seas. The Spanish lifeguards had to risk their lives to scramble onto the Greek coast guard ship to perform CPR on those who had lost consciousness, including a tiny baby.

Their jetskis were damaged in the process.

Long after nightfall, the Spanish volunteers returned to shore, themselves so chilled to the bone that they were risking hypothermia. “We passed so many lifeless bodies floating in the sea as we left the rescue area,”

Gerard said, his voice still shaking a day later. “So many of them were babies. We saw at least 30 bodies at the scene in the water.” By Thursday, 242 people had been rescued, and the Greek coast guard confirmed that at least 34 people remained missing, in addition to the seven bodies recovered from the water the evening before. The ultimate death toll is no doubt even higher, since only families with surviving members were able to report their missing to the coast guard.

In the morning, after that horrific night, the Spanish lifeguards were already back at work, pulling in more boats full of new arrivals, helping those with hypothermia, and providing new dry clothes to those in need. They operate buses to take newly arrivals to the registration camps that are nearly 70 kilometers away, a distance most used to walk before.

Why is it that months into this crisis it is still almost exclusively volunteers who are providing those arriving on Europe’s shores with such life-saving assistance? Why should volunteers still be providing life-saving medical care on the rocks of Lesbos, with not an ambulance provided by any government or inter-governmental organization in sight?

The truth is the debt-stricken Greek government is unable to provide for the huge numbers of new arrivals, even the basics. But what is the European Union doing? It can and should do more to help these often-forgotten victims, by assisting Greece on a plan to protect the rights and well-being of migrants and asylum seekers arriving on its shores. EU member states need to provide human resources, such as doctors, and technical capacity.

There is no doubt that the rescuers faced severe weather conditions during Wednesday’s disaster, with near-gale-winds. Both Frontex and the Greek army deployed helicopters as well as available vessels in the rescue effort. But the reality is that, despite months of pleas for more assistance and preparation, the resources deployed by Greece and the EU remain woefully inadequate for the task at hand, and much of the most dangerous work is done by volunteers.

Sadly, this is the reality not only in Greece, but all along the dismal journey that these people fleeing war and persecution follow through the Western Balkans to reach asylum in Western Europe. All along the route, there is virtually no humanitarian response from European institutions, and those in need rely on the good will of volunteers for shelter, food, clothes, and medical assistance.

When I met the head of the Hellenic Coast Guard on Lesbos three weeks ago, I asked him what he needed to deal with the ever-growing numbers of new arrivals on his small island—over 110,000 in September alone, according to his statistics—and his immediate response was more rescue boats from European countries. He freely admitted that his Coast Guard service was completely overwhelmed, and told me he had been begging for more EU assistance for months.

At a summit last Sunday, EU leaders agreed to increase Frontex presence in the Aegean – essential as thousands are attempting the crossing, hoping to reach Europe before winter sets in. Greece and the EU should act urgently to ensure there are enough boats for rescues there. Until that assistance comes, it will continue to be volunteers who are at the forefront of the effort to save lives.