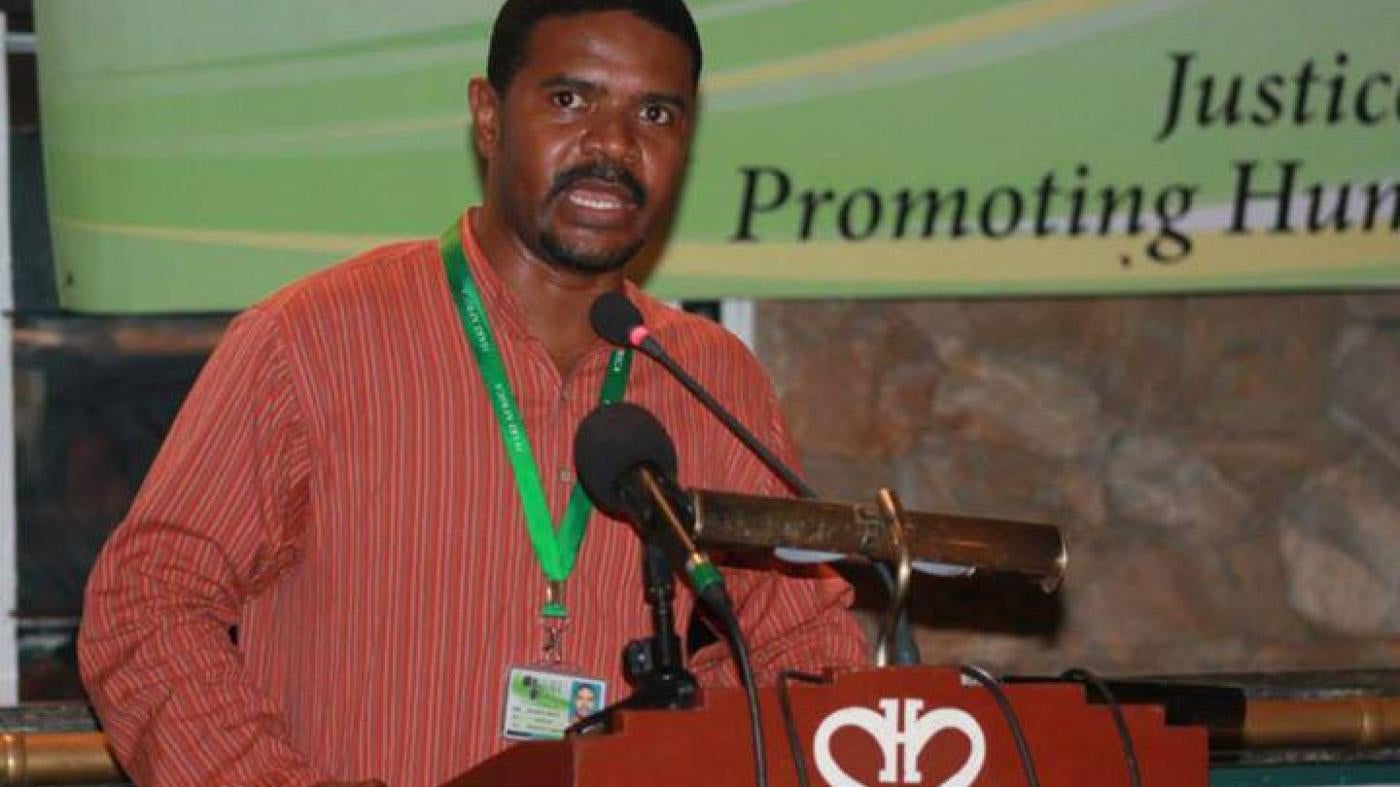

It was April when Kenya’s government froze the bank accounts of the human rights organization Haki Africa. Kenyan officials then raided Haki Africa’s office, taking away their computers and all financial records. Their health insurance company suspended coverage for all staff and their families. Although Haki Africa's director, Hussein Khalid, and his colleagues used their own savings to keep the organization afloat, they finally were forced to close the office in May. In recent days, some of Haki Africa’s employees – including Khalid – have been followed, day and night, even to their homes.

“I’ve taken pictures of cars following me around as I drive,” Khalid said. “But my major concern is my staff. They’re in trouble because of our work. I don’t mind going through this, but when it comes to family and friends, I get extremely, extremely worried.”

These troubles began after Kenya’s government released a list or 86 people and organizations, including Haki Africa and the human rights organization Muslims for Human Rights (MUHURI), for allegedly having links with terrorism. They issued this list in response to the terrorist attack on Garissa University College that left 147, including 142 students, dead. Garissa lies in Kenya’s northeastern region, where the population is mostly ethnic Somali Kenyans. The armed Islamist group al-Shabaab, which is based in Somalia but has carried out numerous attacks in neighboring Kenya, claimed responsibility.

Kenya’s Somali and other predominantly Muslim communities have paid a heavy price for these attacks. Kenya’s security forces have repeatedly responded with widespread beatings, arbitrary detention, torture, and extortion, often targeting whole communities based on religious and ethnic identity. Alleged terrorism suspects have been forcibly disappeared or killed. Haki Africa provided services to some of the communities affected by these abuses.

On Friday, United States President Barack Obama is to visit Kenya. He will meet with Khalid and other rights defenders, as well as government leaders and the political opposition. While there, Obama should build on previous comments Secretary of State John Kerry and US Ambassador Robert Godec made about the important role civil society plays in fighting terrorism, noting that the Kenyan government needs to shift course and reverse its efforts to clamp down on independent organizations and media. This means putting into practice the language Obama used at the February 2015 Countering Violent Extremism summit held in Washington, DC: “[w]hen people are oppressed, and human rights are denied – particularly along sectarian lines or ethnic lines – when dissent is silenced, it feeds violent extremism.”

There is no question that Kenya faces serious security concerns, but silencing activists and independent media while discriminating against entire communities is not only unlawful, it undermines confidence and cooperation with the security forces. It may even help groups like Al-Shabaab, who recruit among frustrated and disenfranchised individuals.

Khalid came to human rights work naturally. “I didn’t grow up in a wealthy background,” he said, describing his childhood in a Nairobi semi slum called Ngara. “Where I grew up, you’d see people tortured by police, families without food, communities not having enough clothing for their children. I wanted to do more to help the less fortunate.”

Haki Africa operated programs focusing on human rights and security, women’s rights, and youth engagement. But 60 percent of its work – the “most crucial segment of our human rights work,” Khalid said – was dealing with the 10 to 15 new cases reported to them each day. The cases ranged from domestic violence to harassment by police, “disappearances,” and killings.

Khalid has worked on a variety of cases. He sued the government after it claimed it didn’t know the whereabouts of Hemed Salim, who had been arrested. He helped a wife leave her abusive husband. When an orphanage was running low on funds, his organization convinced a local entrepreneur to make donations. Now those kids are growing up and going to school.

A member of Haki Africa’s “swift action team (SWAT)” would review each new case and help people fill out forms to report abuses. They encouraged people to report the crimes to the police, who are required under Kenyan law to file charges and make arrests. Haki Africa also helped victims gather evidence, which the organization shared with the police. If the police investigation was moving slowly – as often happens if the complaint is against one of their own – Haki Africa would sometimes go to the media or report the problem to higher officials, Khalid said.

But then came the Garissa attack. Within days of appearing on the list of alleged Al-Shabaab supporters, Haki Africa and MUHURI’s bank accounts were frozen. The government has never produced evidence of these allegations and a high court in Mombasa – the diverse coastal city where Haki Africa is based – ruled in June that the organization didn’t have ties to militants. Despite the ruling, Haki Africa and MUHURI have not been able to get their accounts unfrozen.

Since April, Kenya’s NGO Coordination Board, which regulates nonprofit groups, has accused Haki Africa of underreporting its income, has raised questions about its board composition – without showing any irregularities – and has claimed that Haki Africa is operating illegally, despite its legal hosting under Haki Centre.

“We’re not running at all now,” Khalid said. “We shut down our offices. We are not undertaking any programs or following up on any issues. All we’re engaged in currently is clearing our name.”

Unable to work and investigate cases, Khalid feels helpless. “People tell me they have nowhere to turn, that they don’t trust the police, or that the police are violating their rights. We are working overtime to get our name cleared so that we can get back to helping our community.” What he wants is for the government to “unfreeze our accounts so we can help.”

Kenya’s growing insecurity and abusive reprisals by its security forces are compounding the problems of its poor communities. In the northeast, for instance, dozens of schools have closed since the Garissa attack because many teachers are afraid to be based in the region, which exacerbates the needs – and frustrations – of people there. On the coast, where Haki Africa works, some people claim that their family members have disappeared or been killed. “If it’s not safe to go to school, how do you get an education? How do you go to a hospital if it’s not safe?” Khalid pointed out.

Since the Garissa attack, media reports of security abuses have led Khalid to believe that the numbers of killings and disappearances have skyrocketed –mainly in the northeast, with a few new cases on the coast.

“To know they’re missing and to know we can’t do much to help our community…” he said as his voice trailed off.