As a little girl, Ruth Riviera (not her real name) loved to step into her dad’s army boots and strut around the house with pride and self-importance. Her dad, a Non-Commission Officer in the US Army, was her childhood hero. She admired pretty much everything about him: his creativity, his courage and his attitude that one can accomplish anything one puts one’s mind to. It felt natural to Riviera to follow in his footsteps and sign up for the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC), a military program for students, when enrolling in college at 18.

Fifteen years later, the idealistic young woman, who excelled in college and planned on serving her country as a military leader and role model, is looking back on shattered dreams and the end of her army career. Riviera had dared what most of her colleagues shunned: She had reported male colleagues for sexual harassment.

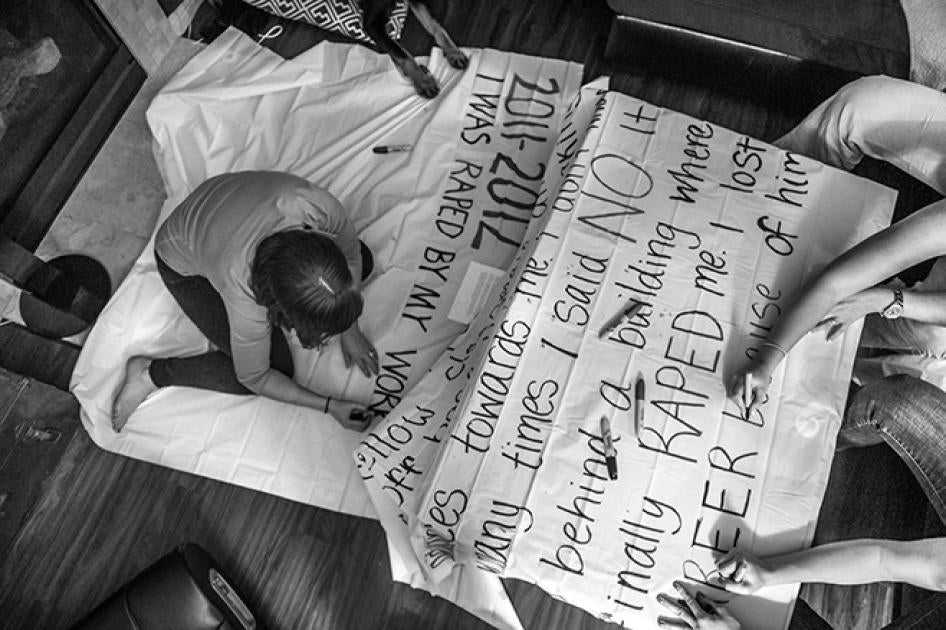

During her nine years in the Army, she had been raped twice by fellow officers and twice groped and harassed in such a manner that she felt her dignity had been severely undermined. She only reported the incidents of indecent conduct. Reporting the rapes, she believed, would have had serious repercussions and would have killed her career.

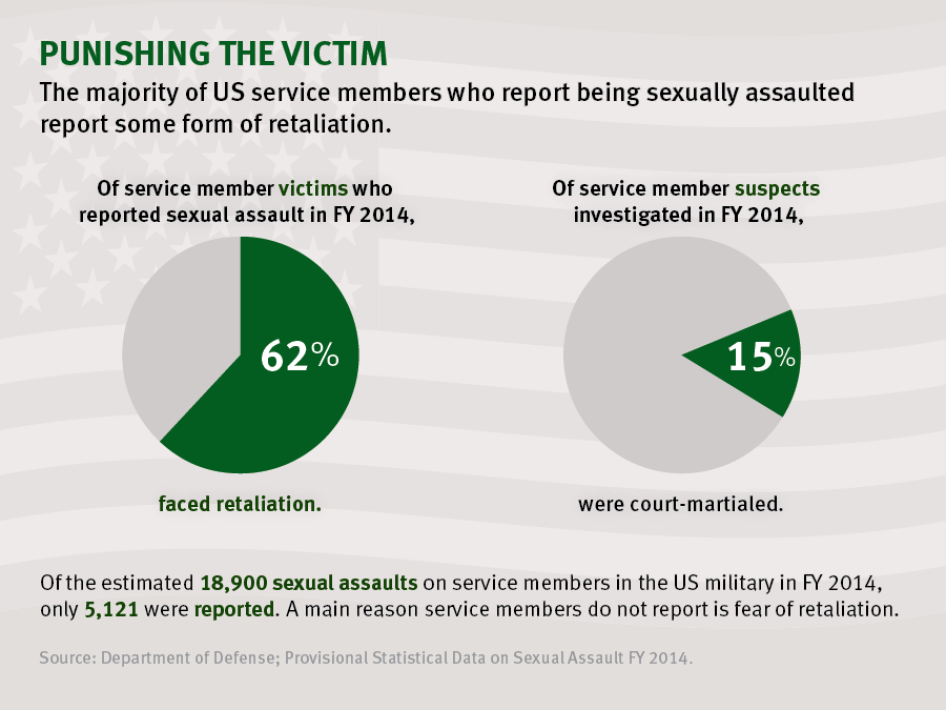

That sexual harassment and assault are a problem in the US military is no secret. Between October 2013 and September 2014 alone, an estimated 18,900 US service members experienced some form of sexual contact or abuse without consent, according to Department of Defense estimates. However, only one in four victims reports these incidents to military authorities for fear of retaliation. The fear, a new Human Rights Watch report finds, is well founded: military personnel who report sexual assault are 12 times as likely to experience some form of retaliation as to see their perpetrator convicted of a sex offense.

Riviera knew the army was a guys’ club. Her father said she was likely to have a hard time because of her determination to excel at whatever she did – something, he warned, people in the army would find intimidating. Thanks to her warm smile and convivial personality, she bonded easily with those around her. But aware of the ever-present sexual overtones, she dressed conservatively, kept her long blond hair tied up at the back of her neck, and ran track.

At college and later during her officer training, she shrugged off the slurs and slippery comments, got on with her studies and her running practice and excelled in both. Her reviews described her as “exceptional,” “tremendous,” and a cadet with “unlimited potential.” Around her neck, she wore a dog tag with the army values both she and her father embraced: “Loyalty, Duty, Respect, Selfless Service, Honor, Integrity, Personal Courage.”

At the age of 25, she had her first Change of Command Ceremony, officially taking on her first command post. She felt both excited and acutely aware of the gravity of her position. That very same evening, her value system and leadership skills would be put to the test.

A 13-year-old girl had been raped by one of the men under her command. She made sure the soldier went to prison. “My soldiers knew that rape is something I would not tolerate,” she told Human Rights Watch. “I firmly believe that as a commander this is a climate you create.”

As commander of a missile defense unit in Oklahoma, Captain Riviera had up to 100 soldiers, mostly men, under her command. She was well liked and had “fun” teaching them a lesson or two about gender stereotypes. “When the guys discovered that I could outrun them, they were totally blown away,” she recalled. “That did not at all fit their idea of women.” By the time the unit was moved to Korea, she had created an atmosphere of mutual respect and a strong bond among the men and women she was in charge of. But her success bred enemies.

When a higher-ranked colleague called her names, brushed against her in hallways, and touched her in inappropriate places, she reported him. Rather than disciplining the offender, however, her commander told her curtly to “deal with it” or be fired.

What followed were two years of harassment. Every training meeting was like running the gauntlet. Even her unit was made to take the brunt: Scheduled evaluation dates were pushed into the future, training and readiness goals could not be accomplished, and her soldiers missed out on promotion points. Rather than justice she had reaped retaliation, like many who dared to speak up.

When she was sexually assaulted later that year, she chose to keep silent. She had witnessed too often how others who had reported sexual assaults had been demeaned, demoted, disciplined, discharged. Rarely were those who committed the offense punished, but the victims were penalized and scorned, she said. Confidential information became public knowledge, and survivors were branded sluts. “So I did what it took to keep my position,” Riviera said. Even if that meant facing her rapists on a daily basis as if nothing had happened.

But sickened by the way other assault victims were being treated, Riviera eventually attempted again to report an incident of groping. “I thought that I would be able to change the attitude toward sexual assault victims by reporting,” she told a Human Rights Watch senior researcher, Sara Darehshori. “I thought reporting would stop the perpetrator from continuing to harass me, or others.”

Her hopes were quickly dashed. Although the Army Criminal Investigation Division substantiated her case and the perpetrator confessed, Riviera was given a rough time. Despite outstanding reviews, she left Korea without a single award for her 24-month service as company commander. “I knew then that this was the beginning of the end of my career,” she said.

Riviera had been branded a troublemaker. But those she had reported for sexual harassment moved on with a clean slate.

She made one last attempt to report an incident of sexual harassment: a drunk first sergeant under her command had made an inappropriate, lascivious comment. Concerned that he might treat other members of her unit in a similar fashion, she counseled him and referred him to the battalion commander. But instead of ordering an investigation, the commander counseled Riviera for failure to maintain better control over the offender, and she herself became the subject of an investigation. Her soldiers were interrogated about “her mood” and asked to report everything she did wrong. “Ma’am, I don’t know what you did,” said one of her soldiers after meeting with the sergeant major who led the interrogation, “but he is gunning for you.”

Nine years after Riviera had entered the army full of enthusiasm and potential, the soft-spoken captain applied for medical retirement. Even to get this approved was a fight, and she was denied a retirement award. Riviera left, grateful for the leadership skills she had honed but utterly disenchanted with the system.

In March 2013, and after Riviera had asked her state senator to look into her complaints, the commanding general finally requested an external investigation and her first sergeant was relieved of duty. For Riviera, this decision came too late to salvage her career. She no longer wears the dog tag with the Army’s values around her neck. “I don’t feel like I need to,” she told Human Rights Watch. “Those values are part of who I am.”