TJ. Hargrave was killed in the North Tower of the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001. More than a dozen years later, his brother Jamie was chosen in a U.S. government lottery to attend a week of pre-trial hearings at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, for the five men accused of plotting the attacks. These may rank among the most important legal proceedings in American history, but news of them made hardly a ripple.

“It’s your obligation as journalists to report these proceedings at least a little bit,” Jamie pleaded at a news conference after the hearings. He was speaking to an audience of nine.

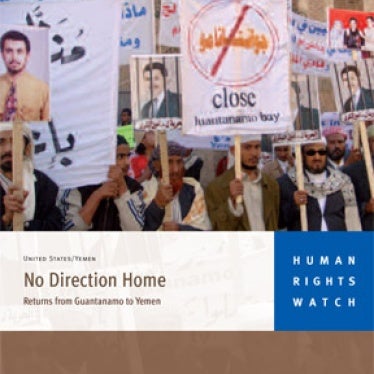

Granted, these are only pre-trial hearings; the coverage may ramp up when the trials begin, probably in 2015. In the meantime, the filing and arguing of motions goes forth with all the drama of drying paint. But this legal wrangling is not the whole story of what’s happening at Guantánamo. And, five years after President Obama vowed to close the controversial prison within his first year in office, the whole story is vexingly hard to tell.

It starts with access. Nobody gets anywhere near Gitmo, let alone the hearings, without permission from the U.S. military, and applying to visit Camp Justice, where the military commissions are held, entails paperwork in quintuplicate. Trial observers like me never see the inside of the prisons, and even journalists never get to talk to the detainees.

Months elapse between sessions of the military commission, and attending in person generally means flying down to Gitmo on a military-organized plane for a whole week. You can’t exactly hop a shuttle and check things out. No wonder media bigshots avoid it.

For outsiders, Guantánamo is weirdly wrapped in a cotton wad of nice. The military minders who shepherd visitors away from restricted areas are paragons of good manners. And since the waters of the bay and the skies above it are relentlessly azure blue, some visitors seem to have a hard time remembering what they came for. The hearings schedule is haphazard, and meanwhile there are pleasure boats to be rented and commemorative T-shirts to be bought (not to mention a Castro bobblehead from Radio GTMO, bearing the inscription “Rockin in Fidel’s Backyard”).

Torture is Guantánamo’s Original Sin. It is both invisible and omnipresent. The U.S. government wants coverage of the 9/11 attacks, but not the waterboarding, sleep deprivation, prolonged standing and other forms of torture that the CIA applied to the defendants. It’s tricky, prosecuting the 9/11 case while trying to keep torture out of the public eye. “Torture is the thread running through all of this,” one of the detainees’ psychiatrists told me. “You can’t tell the story [of 9/11] without it.”

The 9/11 defendants are not being tortured today, at least not in the way they once were. But we don’t know much about conditions in their prison. For years, even its name, “Camp Seven,” was a secret. Proceedings have now ground to a halt while the mental competency of one defendant, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, is evaluated. He kept interrupting the hearings last month with shouts of “This is my life. This is torture. TOR! TURE!”