If officials in a foreign country to which you had fled forced you and hundreds of your compatriots to live in isolation in the desert, surrounded by a fence and armed guards to monitor your every move, limited the public transport available to take you elsewhere during the few hours between mandatory headcounts and gave strict orders to stay inside at night, it would be fair to say that you were in detention.

Israeli officials, however, do not want to use the word "detention" for what is taking place at their new “center” to house Eritrean and Sudanese nationals, mostly asylum seekers, in the Negev Desert. The Holot Center for Residents opened on Dec. 12 with the transfer of 480 migrants there from the Saharonim Detention Center. Officials created the facility after the High Court of Justice ruled in September that detaining asylum seekers in Saharonim was unlawful.

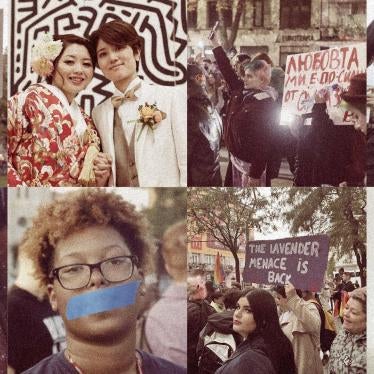

To protest their transfer to the Holot Center, on Dec. 15 about 150 of the African migrants walked six hours through the desert to the nearest city, Beersheba. They continued on Dec. 16 toward Jerusalem, arriving the next day and marching to the Knesset, where the police took them away. Two of the marchers collapsed along the way in the bitter cold. All of them are now detained, once again, in Saharonim.

Israeli news reports quoted a Sudanese asylum seeker saying of the Holot Center, “It’s just like a prison, only the doors are open.”

What exactly is the Holot Center for Residents? A facility built by Israel’s Defense Ministry where the Israeli Prison Service guards hundreds of Eritrean and Sudanese men, women and children. They may be joined by hundreds — and possibly thousands — more under a recently announced plan to expand the facility. A 4-meter (13-feet)-tall fence and the Negev Desert surround the center. Asylum seekers must register there three times a day, to prove they are, well, there. No one may leave between sundown and sunrise. If an asylum seeker breaches, or is even suspected of planning to breach, the center’s rules or threatens the “security of the state” or “public safety,” an Interior Ministry official can order the person’s return to Saharonim for up to 12 months.

Israel’s High Court had ruled on Sept. 16 that a law — which allowed up to three years of detention without trial for foreign nationals who could not be deported to their home countries — breached the right to liberty under Israel’s Basic Law. The court ordered that the authorities had until Dec. 15 to individually review the cases of the 1,708 Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers then in detention at Saharonim and release anyone who had been detained for more than 60 days unless they could be lawfully deported.

How exactly did the Israeli authorities respond to this judgment? First, they failed to release any of the detainees. Only after Israeli refugee organizations accused them in court of being in contempt of the High Court’s judgment did they release 707 of them. Second, the government introduced new legislation, which the Knesset approved on Dec. 10 — Human Rights Day, no less — allowing authorities to detain “infiltrators,” that is, anyone entering Israel irregularly, including asylum seekers, for a year and then transfer them to so-called centers for residents. Thousands of people living in Tel Aviv and other Israeli cities are at risk of detention in Saharonim and then transfer to these “centers.”

According to Israeli procedure since early 2013, asylum seekers who want to be released from this “nondetention” simply have to agree to be deported back to the country where they fear persecution. Under international law and UN guidelines, Israel should only detain asylum seekers as a last resort, as a strictly necessary and proportionate measure to achieve a legitimate aim such as security, not simply for the purpose of coercing asylum seekers to accept “voluntary” deportation.

As for whether this nondetention is really detention, the UN Human Rights Committee has determined that detention occurs whenever someone is confined to a “specific, circumscribed location.” Thus, the Eritreans and Sudanese nationals in the Holot Center for Residents are currently obliged to participate in the legal fiction that they are free to come and go as they wish. If that fiction were true, however, they would be allowed to leave for good and live in towns and cities across Israel while waiting for a determination of their status. They are not.

Miri Regev, chairwoman of the Knesset Interior and Environment Committee, said that the migrants who marched toward Jerusalem were “infiltrators” who were “breaking the new law” by leaving the Holot Center for days, missing their mandatory headcounts. “I hope that when they reach Jerusalem, the police will be waiting for them and take them directly to a closed facility,” she said, according to Haaretz.

Instead of declaring asylum seekers free while finding new ways to detain them, Israeli authorities should simply release them. Officials should fairly examine each asylum seeker's claim, detain them only in exceptional circumstances and never force or pressure them to return to a country where they face serious risk of persecution.