On a warm evening in late April 2013, I was sitting at a Starbucks in Kuwait City across the table from a thirty-one year old woman. Even though “Reem” had undergone male-to-female surgery almost a decade earlier, legal barriers prevented her complete transition to womanhood.

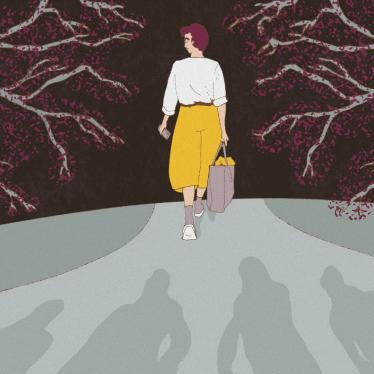

Reem still wore a bulky suit and tie every day to her office to conceal the fact that she was now a woman. When she would go out as herself, she would have to borrow her sister’s ID; luckily, they have similar features.

At the time, I was visiting Kuwait on behalf of Human Rights Watch (HRW) to determine whether the Kuwaiti government had taken steps to end abuses against members of the transgender community, which HRW had documented in its 2012 report, They Hunt Us Down for Fun.

The report focused on violations against transgender women committed by the police. Although the Kuwaiti media has reported about the arrest of a small number of transgender men, HRW found these incidents happen with significantly less frequency than those of transgender women.

According to several lawyers and transgendered individuals, transgender men and boyat—a term commonly used in the Gulf to describe masculine women—generally escape police scrutiny because police fear being accused of harassing women, a charge that is taken very seriously in Kuwait. Women also generally enjoy more flexibility in their dress and presentation, and it is more difficult to define what constitutes gender transgressive dress for women than for men.

To bring Kuwait in line with its international obligations, the situation facing transgendered women in the country must be improved. The first place to start is the law.

Kuwait’s Penal Code: the Law and its Amendment

Reem advised me to “talk to the Parliament – they’re the ones who need to fix the law.”

The law she was referring to—the main reason that Reem feels forced to live a life of constant subterfuge—is Article 198 of Kuwait’s Penal Code, which was amended in 2007 to criminalize, “imitating the opposite sex.” Under this law, transgender individuals are essentially considered criminal imposters.

The real-world impact of the 2007 amendment became painfully clear when Reem’s best friend, “Dalia,” joined us and described a recent experience.

While she was driving home one night, Dalia had car trouble and had to pull over. A policeman pulled up and asked for her papers. On official documents, Dalia, like Reem, is a man—in Kuwait, transgendered people have no legal recourse to change the gender on their ID cards.

The policeman arrested Dalia for dressing as a woman. Ultimately, she spent eight days in prison, for the crime of imitating the opposite sex. Upon release, Dalia was ordered to pay a fine and banned from traveling abroad for seven months. “Now,” she told me, “my biggest fear is a flat tire.”

The two friends are not alone. In Kuwait, many transgender women, who are born male, but identify as female, suffer physical and sexual abuse at the hands of police. The 2007 amendment gives police free rein to determine whether a person’s appearance constitutes “imitating the opposite sex,” without laying down any specific criteria for the offense. Some transgender women have noted that police arrested them for capricious reasons—sometimes because of having a soft voice or other times because of having smooth skin.

According to Ghadeer, a 22-year old transgender woman, the situation in Kuwait was better before the 2007 amendment:

Before the law we had no problems, we would come and go as we pleased and be out in public safely…. When we were stopped at checkpoints and the police would ask us for our IDs and see that we were male they would just smile or even find us cute and let us pass. In the worst of cases they would try to take our numbers to arrange for a date. So there was harassment, but rarely was it as violent as it is now. After the law came out, I started hearing that X was in prison, Y was in prison. I lived in fear and terror. I felt like I couldn’t move, but it is my right to go out, to go to the souk, to go to the doctor.

Thirty-nine of the forty transgender women who HRW interviewed for its report said they were arrested, some individuals as many as nine times. In the majority of cases, the criminal court either acquitted the individual or failed to reach a verdict.

Many of these transgender women claimed, however, that police forced them—by threat or physical violence—to sign declarations stating they would “never again imitate the opposite sex” before releasing them from prison.

Only two of the sixty-two cases resulted in convictions, with penalties of between six months to a year’s imprisonment. Police often detain convicted individuals well beyond what is permitted under Kuwaiti law, typically fail to inform families of their relative’s whereabouts, and/or do not allow convicted individuals to meet with their lawyers.

In some of these cases, police arrested transgender women while they were wearing male clothes, then forced them to dress in women’s clothing, and claimed they were arrested in women’s attire.

All the women interviewed described some form of police abuse, at times rising to the level of torture, degrading and humiliating treatment, and sexual assault or harassment, although the police have denied any mistreatment.

Police have allegedly made women strip and parade naked around the police station, forced them to dance for officers, subjected them to verbal taunts and intimidation, and placed them in solitary confinement.

One transgender woman reported that after being arrested along with two of her friends, the police took a trash can full of dirt and cigarette butts and dumped it over her friend’s head. Her other friend was forced to do push-ups with a radiator on her back.

In another case, a transgender woman who was arrested along with another person reported that police punched and kicked her brutally and beat her friend with a heavy stapler.

In some instances, women reported that police officers used the threat of arrest to force them into sex. Many women said they have not reported incidents of police abuse because they fear retribution and re-arrest.

Kuwaiti authorities consider transgender people to suffer from a bona fide disorder—an inconsistent position, to say the least. While the country’s Ministry of Health recognizes a medical condition it has labeled as “gender identity disorder” (GID), the law criminalizing “imitating the opposite sex” makes no exception for people who have been diagnosed with GID.

Transgender women have described being arrested by police who refuse to recognize, and sometimes even tear up, medical reports and GID diagnoses the women present to them. When Dalia showed the policeman her medical documents, he laughed and ignored them.

Kuwaiti authorities have cited local attitudes toward transgender women as an excuse for repressive laws and policies. Transgender women have reported that ordinary citizens report them to police, encouraged by an unrelenting vilification campaign in Kuwaiti media that portrays transgendered individuals as a destructive force and a threat to the fabric of Kuwaiti society.

Transgendered woman also said that, in the past, hospital doctors have reported them to the police after noting that the gender on their government issued IDs, which they are required to present at medical appointments, does not match their appearance—a practice that effectively limits their access to health care.

This discrimination and persecution is no less a violation of human rights just because it happens to be supported by the majority of Kuwaitis. Kuwait’s policies transgress its human rights obligation to protect residents from arbitrary arrest and detention.

Kuwaiti laws that criminalize a person’s gender expression and identity violate rights to non-discrimination, equality before the law, free expression, personal autonomy, physical integrity, and privacy. Sexual violence committed by police officers acting in an official capacity constitutes torture.

Conclusion

The Kuwaiti government should immediately repeal the 2007 amendment to Article 198. The government also should put in place mechanisms to protect transgender people, a particularly vulnerable group, from police abuse and violence. The government should investigate all allegations of police brutality in an independent, transparent, and timely manner.

As Dalia’s experience shows, in Kuwait today, simply being transgender can be a crime. Parliament should act immediately to make sure this state of affairs is brought to an end.

*Belkis Wille is the Yemen and Kuwait researcher at Human Rights Watch.