California has a hard time letting dying and incapacitated prisoners leave: Over the past two years, an average of 37 prisoners a year received either medical parole (if incapacitated) or a sentence recall (if dying). That's 0.028 percent of the prison population.

There are no national figures, but our research suggests state and federal laws permitting the early release of prisoners who are terminally ill, permanently incapacitated or simply too old to get out of bed are greatly underutilized.

Release on medical grounds is conspicuous by its absence.

In the Federal Bureau of Prisons – which with 218,000 prisoners, operates the largest prison system in the country – 30 prisoners received compassionate release in 2011 and 37 thus far in 2012. At 0.017 percent of the population, that's fewer proportionally than in California. Texas is doing better, with 100 prisoners last year – 0.066 – although hardly a figure to feel good about. New York has never exceeded 10 medical parolees in a year.

Why so few? Officials cite public safety.

Most people would agree that early release on medical grounds would be unwarranted for a prisoner capable of committing a serious crime and likely to do so. The head of the Texas Board of Parole recently suggested that a prisoner on death's doorstep might have a miraculous recovery and commit a serious crime. She didn't point to any statistics on the recidivism of dying or incapacitated prisoners who secure early release. We suspect the cases are few and far between.

In California, the parole board refused on public safety grounds to grant medical parole to Steve Martinez, a man convicted of rape who became quadriplegic while in prison. A court eventually overturned the decision and ordered him released. The Federal Bureau of Prisons also refused on public safety grounds to recommend medical parole for a prisoner convicted of a sex offense against a child, even though severe spinal stenosis had left the prisoner paralyzed from the neck down. In New York, the parole board also rejected medical parole for a rapist who had become quadriplegic.

Becoming a quadriplegic behind bars may be unusual. But these cases exemplify how prisoners are denied medical release not because they would pose a real danger to anyone if no longer incarcerated, but because corrections officials and parole board members are reluctant to support the early release of people who committed heinous crimes.

It is not surprising that some victims or their family members oppose the release of people who did them grievous harm. Public officials, in turn, may be sympathetic to their grief, rage and desire that the prisoner not leave prison "except in a pine box," as one family member said. Officials may also be reluctant to incur the public wrath and political blowback likely to follow the early release of a notorious criminal.

Thus Susan Atkins, who participated in the brutal murders by Charles Manson's "family," died in prison in 2009. She had been denied medical release despite four decades behind bars and long after cancer left her incapable of harming anyone even if she had wanted to.

Common sense is offended when past crimes are automatically – and irrationally – conflated with current risk. In another California case, a lower court speculated that a wheelchair-bound prisoner seeking medical release might wheel down the street to commit a violent crime. Taxpayers are shortchanged by ever-rising prison budgets to cover soaring medical treatment costs and unnecessary security for people who would pose no meaningful risk to public safety if released to their families or nursing homes. There are medically incapacitated prisoners in California whose individual medical care costs hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. Martinez, the quadriplegic rapist, was costing the California prison system $625,000 a year.

As age whittles away their bodies and minds, older prisoners have higher medical costs – and are less likely to pose a public safety risk. In California, for example, prisoners 55 and over constitute about 7 percent of the prison population and 38 percent of medical bed resources. Nationwide, prison medical expenditures for older inmates range from three to nine times higher than those of the average prisoner.

Caring for incapacitated and ill prisoners is especially expensive for states because prisoners are not covered by Medicaid, Medicare or Veterans Affairs medical reimbursement programs, i.e., the state covers all their medical costs with no federal support. In addition, the state pays the high cost of prison staff who guard round-the-clock prisoners who receive care in community hospitals – including prisoners on ventilation who are not likely to get up from their beds and abscond.

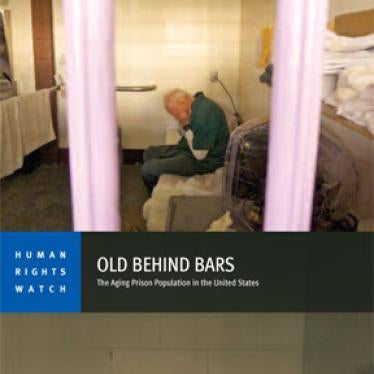

Cost aside, justice is denied when changed circumstances, such as terminal illness or incapacitation, make continued incarceration senseless and even inhumane. A little over a year ago, I met a 68-year-old prisoner in California who had served 10 years for a sex offense. He was blind, suffering from leukemia, and paralyzed except for one arm. He spent his days sitting in a medical unit room staring sightless at the wall.

People who commit crimes must be held accountable. But accountability may not require the continued imprisonment of people who have already spent years behind bars and who have become terminally ill or permanently incapacitated. If they have families willing to care for them, what does the public gain by forcing them to stay in prison? Compassion has a place in criminal justice, even for people who showed no compassion to their victims. And in the case of release on medical grounds, compassion and fiscal responsibility point to the same conclusion.