On a bright day a couple of months ago, I watched old men gather to play bingo in the well-lit common room of a brick building. Some maneuvered around the tables in wheelchairs, some walked on their own.

They were there because they had trouble talking, thinking, remembering. Some were able to put markers on the bingo card when a number was called. Staff helped those who couldn’t.

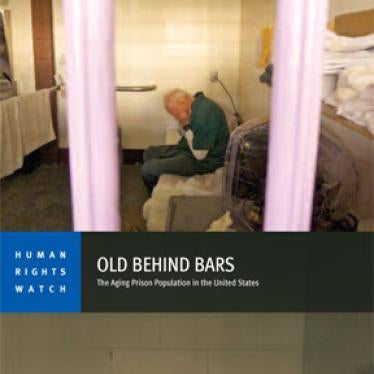

I could have been at an assisted living facility. But this weekly bingo game took place behind razor wire in the Unit for the Cognitively Impaired at the Fishkill Correctional Facility in New York.

Barring changes in sentencing or release practices, this may be the future of corrections. There are at least 26,600 men and women who are 65 and older in United States state and federal prisons. That number has grown by 63% in the last four years. There are another 100,000 prisoners ages 55 to 64.

Even as states try to reduce prison costs and overcrowding, long sentences and restricted parole mean that many of today’s younger prisoners will stay behind bars into their 80s and 90s. One in 10 state prisoners is serving a life sentence. Most of the older prisoners committed serious crimes and are serving long sentences for them.

And many people, crime victims and their families among them, feel that justice demands that murderers and rapists only leave prison “in a pine box.”

But those understandable feelings should not be the sole basis for keeping someone in prison in their waning years. From the perspective of public safety, fiscal prudence and human rights, keeping the old and infirm in prison instead of releasing them to parole supervision makes little sense.

There’s little risk elderly ex-cons will rise from their beds or wheelchairs to commit another crime. The latest recidivism data from New York shows that only eight of the 152 men and women age 65 and older released in 2006 were returned to prison because of a new felony conviction within three years (the standard period for measuring recidivism).

By comparison, 515 of the 4,387 prisoners released at ages 25-39 returned to prison because of new felony convictions.

While visiting 20 prisons across the country last year, I met prisoners with Alzheimer’s, other forms of dementia and severe cognitive impairments — like an 87-year-old prisoner in Mississippi who couldn’t remember when he had entered prison. I also met older prisoners whose minds are fine, but whose bodies have been whittled away by age and disease — like a 65-year-old man in an Ohio correctional medical facility who has been in prison since he was 40 and is dying of metastasized esophageal cancer.

I came away impressed with the efforts of many staff to respond to the unique needs of inmates like these. But it is difficult in resource-starved correctional facilities built and operated with younger inmates in mind.

Prison is tough for everyone, but it is especially hard for older prisoners who need wheelchairs, walkers, portable oxygen and hearing aids; who cannot get dressed, go to the bathroom or bathe without help; who are incontinent, confused or suffering from chronic diseases.

Prison medical costs — borne entirely by the state — are up to nine times higher for older prisoners than for younger ones.

So what can be done? Prison officials, parole boards and governors should make an effort to increase the number of older and ill inmates posing no meaningful security risk who are released from prison and placed under community supervision.

Some of those prisoners could go back to their families. Others could be released to nursing homes or assisted living facilities — although it is increasingly difficult to find private facilities that will take former prisoners, leading a number of states to contemplate the creation of public geriatric facilities that cannot refuse patients simply because they served time in prison.

Going forward, state governments should consider jettisoning mandatory minimum sentencing laws that dictate sentences carrying an offender from youth to old age and even death, without regard to rehabilitation or continued dangerousness.

Those who violate the rights of others must be held accountable. Prison sentences are tailored to give offenders their just deserts at the time of sentencing.

But age and illness (not to mention evidence of rehabilitation) can change the calculus.

If elderly prisoners can be safely released from prison to finish the rest of their lives under parole supervision — at much lower cost to taxpayers — it is hard to see what society gains from keeping them behind bars.

Fellner is senior adviser at Human Rights Watch and the author of “Old Behind Bars: The Aging Prison Population in the United States.”