Rehab here may be hard but it has nothing on drug "treatment" in Vietnam, where tens of thousands of unfortunate users are detained in forced labor camps and tortured and beaten. Even worse, international donors and aid groups actually work inside these detention centers, providing funding and a fig leaf to an extremely abusive system.

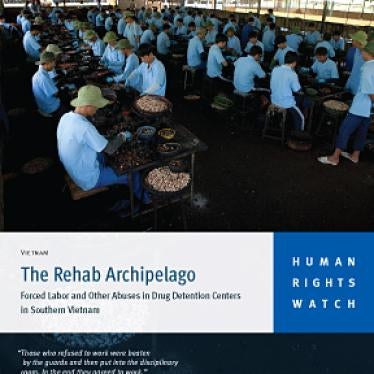

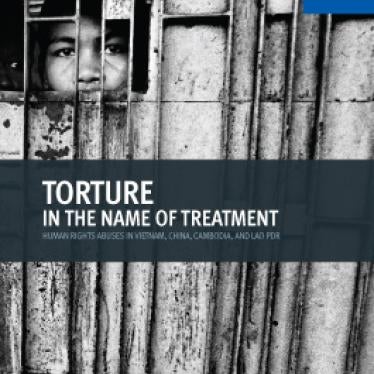

The Human Rights Watch report on Vietnam's system of so-called drug "treatment" centers, "The Rehab Archipelago," found that drug users are detained for up to four years without ever being charged or tried, and are routinely beaten, shocked with electric batons, and locked in isolation cells or punishment rooms.

Former detainees described working in cashew processing, potato or coffee farming, construction, and manufacturing garments, bamboo and rattan products. Some weren't paid. Others were paid well below the Vietnamese minimum wage, their meager wages reduced even further by charges for food, accommodation and "management fees." The centers, meanwhile, make a handsome profit from these businesses.

Such abuses are happening on a massive scale: 123 such centers hold some 40,000 people. Between 2000 and 2010, some 309,000 people passed through the centers -- and all of them worked for the privilege.

Despite this state-orchestrated abuse, international donor and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are deeply engaged in these centers. Many groups work inside such centers and project staff from aid agencies and NGOs visit on a regular basis. The most senior foreign officials in Vietnam -- ambassadors, country managers and UN agency heads -- periodically drop by. In 2009, international donors gave over $100m for HIV programs in Vietnam.

Despite such engagement, there's been little outcry over forced labor and no coherent donor position on how to end this vast system of forced labor camps. Some donors and implementing agencies don't think there's a problem. Others are concerned but divided about how to respond.

The Vietnamese government has used donor involvement to provide a veneer of legitimacy to the centers and, in response to Human Rights Watch's report, claimed that its system was "in line with the principles of effective drug addiction treatment released by the (U.S.) National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and agreed by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) -- World Health Organization (WHO)."

This claim is false: torture and forced labor are not recognized as principles of effective drug treatment by any of these agencies, and the United Nations in Vietnam has said clearly that Vietnam's drug detention centers are ineffective, abusive and facilitate HIV transmission.

But the Vietnamese government has grounds for pushing this lie. Over the last few years, UNODC has provided training and funding for detention center staff, and has failed to clearly address the human rights principles around compulsory "treatment." UNODC says forced labor should not be used as drug treatment, but when we specifically asked if their training of Vietnamese center staff covered that point, they said the question was "not applicable."

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has also funded trainings for government addiction counselors, including the point that "treatment does not have to be voluntary to be effective." To date, USAID has not revealed whether those trainings note that forced labor is not drug treatment and is banned by international and Vietnamese law. The training manuals certainly don't say so.

The U.S. Department of State's human rights report describes the centers as "forced detoxification labor camps." Yet State has funded training in 20 centers to create "therapeutic communities." State claims its trainings led to "improved communication between residents and staff" and "fewer escape attempts." But the U.S. opposes the extrajudicial confinement of individuals in forced labor camps -- so shouldn't U.S. funding be promoting and measuring successful escape attempts?

The UK's development agency, which funds projects on HIV prevention among injecting drug users in Vietnam, has stated unequivocally that it would never fund services in the centers. Meanwhile DFID's partner in Vietnam, the World Bank, has stated to Human Rights Watch that its own work in the centers is a humanitarian necessity and that it is not aware of any abuses.

The list goes on, including the Australian development agency and the Global Fund to Fight HIV, TB and Malaria. A Global Fund spokesperson recently stated that "it is utterly irresponsible not to supply [the centers] with drugs to combat HIV and TB [tuberculosis]." But Global Fund staff told me that they were well aware of the abuses in the centers, and yet they asked no questions, looking away from torture, forced labor and other abuse. I find that "utterly irresponsible."

Moreover, detainees who are seriously ill and can't be treated in drug detention centers have a legal right to be released and receive care in a community hospital or back home. So the Global Fund's support for healthcare inside the centers keeps sick patients detained and forced to work, allowing center directors to maximize profits and minimize expenses.

Despite the concerns, USAID intends to expand its engagement, providing healthcare for detainees inside detention centers. But when detainees complain to doctors paid by the Global Fund or USAID, and say they were beaten up for refusing to work, will the doctors patch them up and send them back?

Surely it would be better for USAID and other donors to support drug users in the community -- to provide effective treatment and legal services to keep them out of abusive camps. Or to use their considerable leverage to insist that treatment be given in hospitals, clinics or even at home.

When dealing with HIV and drug dependence, community-based alternatives are less expensive, more effective, and respect human rights. Donors who purport to care about health and human rights should make very clear that Vietnam should shut the centers now.

Joe Amon is director of health and human rights at Human Rigths Watch