Update: In 2012, ICE issued a directive limiting transfers of immigrant detainees. For more information, please click here.

-----

(Washington, DC) - Detained immigrants facing deportation in the United States are being transferred, often repeatedly, to remote detention centers by US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Human Rights Watch said today in a report analyzing 12 years of data.

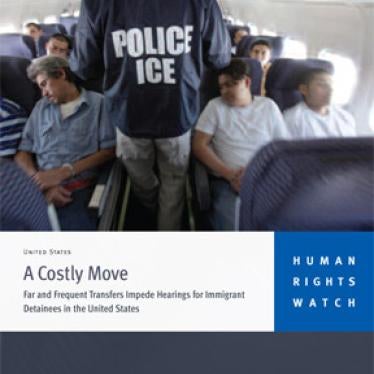

The 37-page report, "A Costly Move: Far and Frequent Transfers Impede Hearings for Immigrant Detainees in the United States," says transfers separate detained immigrants, including legal permanent residents, refugees, and undocumented people, from the attorneys, witnesses, and evidence they need to defend against deportation. That can violate their right to fair treatment in court, slow down asylum or deportation proceedings, and extend their time in detention, Human Rights Watch said.

"Transfers don't just move people, they push aside their rights," said Alison Parker, US program director and author of the report. "They can prevent immigrants, like those lawfully here or in need of asylum from persecution, from having an attorney or defending their right to remain in the United States."

Interactive Dashboard: State by state breakdown, top 20 sending and receiving facilities >>

Human Rights Watch's analysis of 2 million transfer records over 12 years shows that over 46 percent of transferred detainees were moved two or more times. One egregious case involved a detainee who was transferred 66 times. On average, each transferred detainee traveled 370 miles; and one frequent transfer pattern (from Pennsylvania to Texas) covered 1,642 miles. Such long-distance and repetitive transfers can make attorney-client relationships unworkable, separate immigrants from the evidence they need to present in court, and make family visits so costly that they rarely, if ever, occur.

One immigration attorney said, "I have never represented someone who has not been in more than three detention facilities. Could be El Paso, Texas, a facility in Arizona, or they send people to Hawaii.... I have been practicing immigration law for more than a decade. Never once have I been notified of [my client's] transfer. Never."

Data tools produced by Human Rights Watch allow users to view maps of the United States, tracing the trajectories of the starting and ending points of the largest numbers of transfers. The tools also provide interactive graphs that provide users with state-by-state analysis and trends in detainee transfers across time.

The largest number of transfers between states involves detainees sent to Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas - states within the jurisdiction of the federal Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. These are of particular concern, Human Rights Watch said, because that court is widely known for decisions that are hostile to immigrants and because the three states collectively have the worst ratio of immigration detainees to immigration attorneys in the country: 510 to 1.

A legal permanent resident originally from the Dominican Republic, who had been living in Philadelphia but was transferred to Texas, said, "I had to call to try to get the police records myself. It took a lot of time. The judge got mad that I kept asking for more time. But eventually they arrived. I tried to put on the case myself [without an attorney]. I lost."

With close to 400,000 immigrants in detention each year, space in detention centers, especially near cities where immigrants live, has not kept pace. As a result, ICE has built a detention system - relying on subcontracts with state jails and prisons - that cannot operate without transfers. In the 12 years analyzed in the report, ICE has carried out 2 million transfers involving 1 million immigrants. Between 2005 and 2009, the use of transfers more than doubled. And 57 percent of all detainee transfers moved people to and from subcontracted state or local criminal facilities, which transfer ICE detainees once again when they need the beds for state criminal inmates.

The report estimates that transportation alone for 2 million transfers has cost $366 million. But transferred detainees spend more than three times as long in detention as those who remain in the same place, so the greatest financial costs may come from court delays and extensive periods of incarceration, Human Rights Watch said.

Transfers have not significantly declined despite repeated promises by ICE to change its transfer practices. The agency has announced plans to create a new detention facility in New Jersey, closer to some cities where many immigrants live, and where their attorneys and witnesses are located. It has also instituted a detainee locator system, which now allows lawyers and family members to find their clients or loved ones after a transfer. The locator system does nothing to reduce the transfers.

Human Rights Watch acknowledged that some transfers are inevitable, but said that ICE and Congress should use reasonable and rights-protective checks on detainee transfers as the best state criminal justice systems do. The report recommends concrete steps to help create such a system.

"The ICE buses and planes that crisscross the United States bring dire consequences for detainees and for ICE," Parker said. "But so far ICE has taken few steps to end its dependence on this chaotic game of detainee musical chairs."