(Brussels, May 4, 2010) - The Uzbek government is vigorously persecuting the relatives of people it suspects of links to demonstrations in the eastern city of Andijan five years ago, when government forces killed hundreds of mostly unarmed protesters, Human Rights Watch said today.

New research by Human Rights Watch reveals that the Uzbek government continues to intimidate and harass the families of Andijan survivors who have sought refuge abroad. The police regularly summon them for questioning, subject them to constant surveillance, and threaten to bring criminal charges against them or confiscate their homes. School officials humiliate refugees' children. Five years after the massacre, on May 13, 2005, people suspected of having participated in or witnessed the massacre are still being detained, beaten, and threatened. The sentencing on April 30 of Diloram Abdukodirova, an Andijan refugee who returned to Uzbekistan in January, to 10 years and two months in prison, shows the lengths to which the government will go to persecute anyone it perceives as linked to the Andijan events.

"Instead of ensuring justice for the victims of Andijan, the Uzbek government persecutes anyone associated with the protesters," said Holly Cartner, Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. "There is a climate of fear in Andijan that is still palpable five years after the atrocities."

In March and April 2010, Human Rights Watch interviewed 24 individuals who had fled persecution in Andijan. Some of them fled Uzbekistan in 2005 and have long been resettled, while others fled Uzbekistan over the last six months. They described Andijan as a place where their relatives live in constant fear.

A woman who fled Andijan recently said her mother was too afraid to allow her daughter to stay in her house. Another described how the neighborhood policeman repeatedly questions the man's elderly mother and pressures her to denounce her son as a "terrorist." A third refugee, who recently fled Uzbekistan, described how the security service repeatedly summoned him for questioning, as recently as December, and beat him.

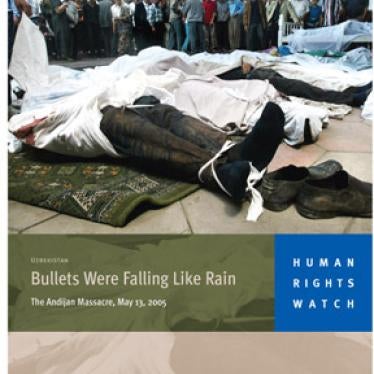

The violence in Andijan began early on the morning of May 13, 2005, when gunmen attacked government buildings, killed security officials, broke into the city prison, and took hostages. A public protest followed, with thousands of demonstrators airing grievances about the government. Government forces started shooting at the crowd indiscriminately. As people fled, government forces ambushed and killed or wounded several hundred people, the vast majority of them unarmed.

The Uzbek government has not held its forces accountable for these killings. The government instead unleashed a fierce crackdown on civil society, imprisoning human rights defenders, independent journalists, and political activists who spoke out about the Andijan events and called for accountability for the killings. Hundreds of individuals accused of involvement in the armed attacks and protests were convicted and sentenced following trials that were, with one exception, closed. The one public trial was riddled with due process and fair trial violations. The 15 defendants did not have access to competent and effective counsel and were not able to mount an effective defense, in violation of their fundamental human rights.

Although the European Union and the United States initially condemned the killings and called for an independent investigation, they have stopped calling publicly for accountability for Andijan. Human Rights Watch urged the EU and the US to use the occasion of the fifth anniversary to remind the Uzbek government of its obligation to identify and punish those responsible, compensate the victims, and end its persecution of the families of suspected protesters. The EU and US should also press Uzbekistan to stop persecuting civil society activists and release all human rights defenders and others wrongfully imprisoned for human rights work. At least 14 human rights defenders are in prison on politically motivated charges.

"International silence in the face of impunity for the Andijan massacre has had disastrous consequences for the cause of human rights in Uzbekistan," Cartner said. "Neither the Uzbek government nor Uzbekistan's international partners should be allowed to forget the atrocities that were committed in Andijan."

The recent interviews revealed new episodes of persecution, similar to those Human Rights Watch documented in its May 2008 report "Saving its Secrets". Human Rights Watch has documented the Uzbek government's attempts to silence massacre survivors and witnesses with arbitrary arrest, torture, and threats to their lives, as well as sustained harassment. The names of those interviewed for this new report were changed to protect them, and there is no continuity of the pseudonyms with any earlier report.

Climate of Fear

A climate of fear persists in Andijan five years after the massacre. Although the Uzbek government attempts to portray Andijan as a closed chapter, the refugees said they still fear repercussions for their relatives back in Andijan.

Their relatives are subject to constant surveillance - by mahalla (local neighborhood) committees, the police, and the National Security Agency (SNB) - and are under constant threat of persecution by the authorities.

"[The authorities] know everything," said Shakhnoza Sh., who fled Uzbekistan earlier this year. She described how terrified her own mother was of associating with her. "It was cold at my house because there was no gas [pressure], so I went to stay with my parents," she said, describing the winter that just ended. "My mother, who is an old woman, a pensioner, was afraid to have me there, afraid they'd put her in jail. She loves me, but she is afraid for my brothers and herself [that they will get arrested]. She asked me, ‘Are they going to lock me up because of you?' She didn't want me there, her own daughter, because she was afraid and said I should go to my husband [abroad]."

Other refugees told Human Rights Watch that their relatives in Andijan refuse to speak to them by phone, fearful they will face more harassment, or possibly lose their jobs.

"It's been five years and even now we can't speak normally by phone," said Salim S. "I limit my phone calls home because, while it's easy to pick up the phone here, for people back home, it could be dangerous."

Regular Police Interrogations

The refugees described a pattern of government harassment. Police summon relatives, interrogate them, demand that they write explanations about their activities, order them to provide official documents for no apparent reason, and call on them at their homes and places of work repeatedly. Human Rights Watch documented a similar pattern of harassment in 2008.

Almost all of the refugees interviewed recently said their relatives are summoned by the police once or twice a month. Most of those interviewed said their relatives are obliged to answer the same questions over and over again, including where their relatives abroad live and work, whether they send home money, how much and how it is spent. They are also forced to write explanatory statements about their activities, including where they go and whom they visit.

Anvar A. told Human Rights Watch that the neighborhood policeman summons his elderly mother for questioning or visits her house about every 15 days. She is forced to write a report (otchet) about any contact she has had with her son, whether he has sent her money, and related issues. In January, the police officer reportedly told her that if she would write a statement denouncing her son, call him a "terrorist" and an "enemy," they would stop calling her in for questioning. In an effort to end the harassment, she complied, but the harassment continues, he said.

"Sometimes the police visit the house at night, around 8 or 9 p.m.," he said. "They say to my mother that I must have returned to see my children and that I am hiding in the house. They search the whole place. Then they count everyone in the household to make sure no one has left Uzbekistan. It's a type of moral pressure."

The local authorities also harass family members by requiring them to submit documents such as health certificates, photocopies of passports and house registries, and character references written by the mahalla committees.

Arbitrary Detention and Ill-Treatment in Custody

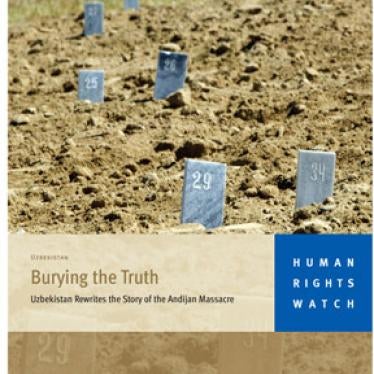

In a September 2005 report "Burying the Truth", Human Rights Watch documented how the Uzbek police arbitrarily detained, tortured, and ill-treated hundreds of individuals in the aftermath of the Andijan massacre. Human Rights Watch continues to receive new reports of such abuse.

Tolib T., who recently fled Uzbekistan, told Human Rights Watch that he had been summoned periodically by the National Security Agency (SNB) since the massacre and was summoned again in early summer 2009. The officers tried to pressure him into saying that a friend of his had been carrying weapons on the day of the massacre. He was forced to write an explanatory note, even though he denied knowing about any weapons. He said the officers told him they would put him in prison unless he found where the weapons were hidden. He said he was beaten for hours during the interrogation.

"First there was one guy, then another guy, and then a third," he said. "They took turns beating me. I was a living ball; they kicked me, hit me, and threw me around. I told them that we didn't have any weapons."

He was summoned again in December. "I don't know why they called me in," he said. "I didn't have to write or sign anything. I went with my sister. There was another woman there waiting for her son. He's 17 years old. They also questioned him. He was only 12 years old in 2005." He said the officers beat him for half an hour. "They called me in to humiliate me, to beat me. At the end they wanted to know if anyone had spoken to me about the dead bodies that were taken away in trucks from the square on May 13. Later my sister told me that the mother waiting for her son [had said] that her son was beaten so badly that he needed to take medication for his heart and blood pressure."

Another refugee, Nodir N., told Human Rights Watch that his brother, who had been resettled in the United States and then returned to Andijan, is detained by the authorities at the police station for several days before each national holiday as a preventive measure. The brother is held with other detainees in a large room with tables but no beds, Nodir N. said, and the authorities do not give him food.

Harassment of Children in School

The persecution of the families of Andijan refugees extends even to their children, some of whom were infants when their parents fled Uzbekistan. They are singled out as the children of "criminals," "traitors," and "enemies of the people."

Several of the refugees told Human Rights Watch that school officials have singled out their children during the morning line-ups (lineika) and told them that they are children of "enemies of the people." Two of the women interviewed said that teachers had told their sons that they would never be accepted at the institute (a college) because their fathers are "bad people." The teacher later confided to one of the women that she knew that her son was actually a good student and that her husband was a good person, but that the teachers had been told they must publicly denounce such children.

Shakhnoza Sh., one of the two women, said her teenage son was being followed by the police. She described how one day he came home and told her, "Mama, I keep seeing the same man, the same face following me everywhere."

Confiscation of Andijan Homes: The Case of Khilolahon Khuzhanazarova

Several of those interviewed said the government is threatening to confiscate the homes of their relatives in Andijan, reportedly as compensation for damage to state property during the massacre. In several cases reported to Human Rights Watch, the households consist of women, all of them caring for young children, whose relatives were imprisoned or fled Uzbekistan after the massacre.

One case researched by Human Rights Watch concerns Khilolahon Khuzhanazarova, the widow of Mukhammadshokir Artikov, one of the 23 businessmen whose trial in Andijan led to the May 13 protests and one of the 15 who were found guilty by the Supreme Court of Uzbekistan in November 2005 of organizing the Andijan violence. Khuzhanazarova lives in an apartment in Andijan with her three children.

In its judgment, the Court found Artikov and the 14 other defendants liable for damage caused to government property. The verdict was never made public, but the Andijan City Judicial Department issued an order on February 14, 2006, to execute its terms. The order, a copy of which Human Rights Watch obtained, states: "the defendants must collectively pay damages to the State in the amount of 4,231,355,133 som [about US$3 million]." The same department informed Khuzhanazarova that her apartment will be confiscated.

Khuzhanazarova appealed to the Kurgantepa Inter-district Court to have her apartment "removed from the list of property subject to confiscation." On May 14, 2009, the Court refused to consider her appeal, on the grounds that "Khuzhanazarova Kh. is not found to be an interested party in this case, since [her husband] Artikov died and she does not have a notarized certification that she is heir to this apartment."

Khuzhanazarova appealed that decision, and on June 30, 2009,the Andijan Regional Civil Court, citing the Family Code of Uzbekistan, which states that property acquired during a marriage is to be considered collective property, quashed the Kurgantepa Inter-district Court's ruling.

However, Khuzhanazarova has made multiple attempts to have the decision to confiscate her apartment overruled, but courts of various instances have denied her request, including most recently the Andijan Regional Civil Court on April 1, 2010.

Several other Andijan refugees said that local authorities, including court bailiffs and representatives from the prosecutor's office, have repeatedly come to their relatives' homes to tell them that their homes are under threat of confiscation. Komil K. told Human Rights Watch that his sister, who lives in his apartment in Andijan and cares for his five children, was recently told by an official that the apartment was going to be confiscated and that she had to move out. Komil K. said that in response to her question about where the children would live if they were forced out of their home, the official replied, "Just put them in an orphanage."

Pressure on Relatives to Secure Refugees' Return

The refugees said that Uzbek authorities actively seek the return of Andijan refugees living abroad, using propaganda, pressure on their families, and promises. Human Rights Watch documented similar tactics in 2008. During the repeated interrogation sessions with family members, Uzbek authorities typically threaten and coerce them to pressure their relatives to come home. They promise that it is safe for refugees to return, that they will encounter no persecution, and in a number of instances have assured their family members that they "guarantee" the returnees' safety.

Shakhnoza Sh. told Human Rights Watch that the authorities would say: "Everything is fine. Your husband is forgiven. He just needs to come home." Other times they would threaten her, saying "If you do not convince him yourself, we'll put you in prison and then your husband will come back for you."

Umar U., another refugee, said that in September 2009, the neighborhood policeman came to the house in Andijan where his wife and daughter live and told them: "We know where your father and brother are...if they don't come back voluntarily, we can extradite them through Interpol," the international police organization.

Arbitrary Arrests: The Case of Diloram Abdukodirova

Despite Uzbek government promises, refugees who return have been arrested.

Diloram Abdukodirova, who fled to Kyrgyzstan on May 13, 2005, and was later resettled in Australia, returned on January 8, 2010, after local authorities repeatedly assured her family that she could return without fear of punishment or reprisal.

She was put on trial, though, on April 21, at the Andijan City Court on multiple charges, including illegal border crossing and anti-constitutional activity. Just over a week later, on April 30, she was sentenced to 10 years and two months in a general regime prison.

During one of the hearings, on April 28, Abdukodirova had bruises on her face, said a family member who was present. Her relative said that she had lost a lot of weight and would not make eye contact with family members.

During the same hearing, Abdukodirova reportedly confessed to all the charges, including the prosecutor's accusation that she had organized a busload of people to participate in the demonstration on May 13, 2005. However, at the next hearing, she again pleaded innocent to the charges, except for having unlawfully crossed the border into Kyrgyzstan in 2005.

When she returned to Uzbekistan, Abdukodirova was stopped at passport control at Tashkent International Airport for not having an exit stamp in her passport. The Tashkent police questioned her, held her for four days, charged her with illegal border crossing, and then released her.

At the end of January, Abdukodirova's case was transferred to the Andijan City Police Department, and the investigator's office repeatedly summoned her for questioning. On March 12, the authorities again detained her.

She has been held ever since in a detention cell in the Andijan City Police station. Initially she did not have access to legal counsel, as her government-appointed lawyer was allegedly on a business trip in a different part of Uzbekistan. The lawyer her family hired to represent her met with her once, then dropped the case. Her family fears he may have come under pressure from the authorities. Abdukodirova's family reportedly approached about 50 lawyers before another finally agreed to represent her. The family fears the new lawyer also faced threats from local authorities.

Abdukodirova's husband and children had been under constant government surveillance since she fled Uzbekistan. Each month her husband was required to report to his neighborhood police officer and confirm that no one from his family had fled Uzbekistan. During these sessions he was reportedly frequently asked about his relatives abroad and required to provide information about their activities.

After Abdukodirova was arrested, the police summoned her relatives and warned them not to organize any demonstrations in her defense. Mahbuba Zokirova, Abdukodirova's sister and the only person to testify at a Supreme Court hearing in November 2005 that government troops opened fire on the crowd, was summoned to the police station and forced to sign a statement promising not to picket in her sister's defense.

Background: The Andijan Massacre

Uzbek government forces killed hundreds of unarmed people who participated in the demonstration in Andijan on May 13, 2005. Protesters were ambushed by government forces and gunned down without warning as they ran from the square. While a small number of those fleeing were armed, government forces fired indiscriminately and made no apparent effort to refrain from using lethal force except in situations that were strictly unavoidable to protect lives, as required by international law. This stunning use of excessive force was documented by the United Nations and other intergovernmental organizations.

Despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary, government authorities continue to deny responsibility for the killings of unarmed protesters in Andijan. The government put the death toll at 187, acknowledging only approximately 60 protester deaths, and attributing all of those to gunmen in the crowd, not to government forces. The real number of civilian deaths is estimated to be several times the official government number.

No one has been held accountable for the killings in Andijan. The government has made no attempt to clarify the circumstances surrounding the massacre, and has categorically refused to allow an independent international inquiry despite repeated calls by international bodies. As recently as March 11, when Uzbekistan's human rights record came up for scrutiny by the UN Human Rights Committee in New York, Akmal Saidov, director of the National Human Rights Centre and the head of the Uzbek government delegation to the review, insisted that what happened in Andijan "was an internal matter for the State and did not require an international investigation."

The Uzbek government suppressed and manipulated information about the massacre and arrested hundreds who participated in the demonstration or witnessed what happened. Human Rights Watch documented the stories of many of these men and women, who were arbitrarily detained and tortured or otherwise ill-treated. Between September 2005 and July 2006, at least 303 people were convicted and sentenced to lengthy prison terms in 22 trials, all but one closed to the public.

The EU responded by imposing sanctions: a visa ban on 12 Uzbek officials considered to be "directly responsible for the indiscriminate and disproportionate use of force in Andijan," an embargo on arms trade, and partial suspension of the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA), the framework that regulates the EU's relationship with Uzbekistan.

However, over the ensuing four years, the EU incrementally weakened the sanctions and on October 27, 2009, scrapped even the arms embargo - the last remaining, and largely symbolic, portion of the sanctions policy - justifying the move as "a good-will gesture" to the Uzbek government to encourage human rights improvements. Starting in 2007, the EU ceased to call publicly for an international investigation into the killings.

Instead, the EU has focused on short-term, incremental steps such as access for UN human rights experts and release of imprisoned human rights defenders. The Uzbek government has persistently defied the EU's calls for human rights improvements, all the while seeking out and punishing people it claims were involved in the Andijan protest, as well as their relatives.

The United States, initially outspoken and robust in its condemnation of the Andijan massacre and in calling for accountability, became increasingly silent after the Uzbek government announced in July 2005 that the US had 180 days to withdraw its forces from a military base in southern Uzbekistan that it had used since 2002 to support operations in Afghanistan. The visibly weakened stance of the United States on human rights in Uzbekistan has been interpreted by many as a conscious choice to safeguard other interests, including access to Uzbek territory and airspace for the resupply of US forces in Afghanistan.

In December 2007, more than two and a half years after the Andijan massacre, the US Congress passed legislation setting out specific human rights benchmarks that the Uzbek government would have to fulfill, or risk facing sanctions, including a visa ban. While welcome, this legislation has not spurred either the Bush or Obama administrations to press Uzbekistan vigorously and publicly to respect human rights, or diminished the US Defense Department's interest in restoring close ties with the Uzbek government.

Recommendations

The EU and the US should use the upcoming anniversary of the massacre as a platform to condemn the rampant human rights abuses in Uzbekistan, specifically including those in Andijan, and to call on the Uzbek government to cease persecution of the Andijan refugees' relatives. The EU and US should renew their calls for those responsible for the excessive use of force against the unarmed demonstrators to be brought to justice and should consistently and repeatedly press the Uzbek government to ensure accountability for the massacre at Andijan.

The EU and US should also intensify pressure on the Uzbek government to address the broader range of serious human rights concerns - including persecution of human rights defenders, rampant torture and ill-treatment, and the impunity with which it occurs, religious persecution, severe restrictions on freedom of expression and the press - that have only been exacerbated in the five years since the Andijan massacre.

To the government of Uzbekistan:

- - Cease all harassment of those believed to have been involved in or to have information about the Andijan protests;

- - Stop harassing the families of Andijan refugees and pressing them to convince their relatives to return;

- - Ensure that all those who wish to return to Andijan can do so in safety and dignity, without fear of arbitrary arrest and persecution;

- - Allow independent human rights monitors, including nongovernmental human rights organizations, UN Special rapporteurs and other intergovernmental experts, as well as the media, both domestic and international, to work unfettered in Andijan, and throughout Uzbekistan;

- - Release immediately and unconditionally all wrongfully imprisoned human rights defenders and other activists.

To Uzbekistan's international partners, including the EU and the US:

- - Urge the Uzbek government to cease the harassment of family members of Andijan prisoners and refugees, including Diloram Abdukodirova and Khilolajon Khuzhanazarova and their families. Use multilateral human rights dialogues and bilateral and multilateral high-level meetings with Uzbek government officials to raise concerns about these abuses and call for them to stop. Continue to emphasize the need for a credible, impartial, and independent inquiry into the Andijan massacre;

- - Urge the Uzbek government to allow full access to Uzbekistan, including Andijan, for independent human rights monitors, including nongovernmental human rights organizations, UN special rapporteurs and other intergovernmental experts, as well as the media;

- - Urge the Uzbek government to release, immediately and unconditionally, all wrongfully imprisoned human rights defenders and other activists.