If there is any surprise inside governments or the UN over the Burmese military regime's obstruction of international aid efforts following the devastating Cyclone Nargis, then they haven't been watching the country closely enough.

As UN aid agencies and other international relief groups desperately tried to increase the amount of clean water, food, shelter and medical assistance to survivors in the Irrawaddy Delta, the ruling State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) refused to allow most aid and aid workers in to help. British, American and French ships sitting just offshore - not to invade, but full of aid and technicians ready to help those in need - were refused permission to unload by the SPDC.

The world sees this as callous neglect of the welfare of the citizens of Burma, but the regime continues in its self-delusional path of ‘disciplined democracy', arguing that the military is the only institution capable of keeping the country united and bringing development. But development never comes - except for the generals and their business cronies, who are now fabulously rich and lead five-star lives.

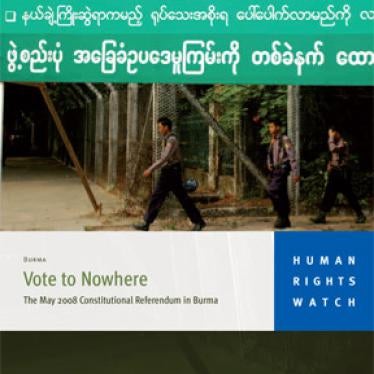

That the generals don't deliver on rights or emergency aid doesn't matter, as virtually any resistance or questioning of their rule is seen as mutinous or a plot from the outside world and is crushed. Every few years public anger erupts, as it did last September when brave monks led peaceful protests. But the army quashed the uprising with the full might of the state. To add insult to injury, just after the cyclone hit the regime persisted in holding a referendum on a new constitution that would legalize and institutionalize military rule. Borrowing a page from despots the world over, it announced 92 per cent approval by voters.

So why doesn't the world react more strongly? Aside from the times when Burma lands itself on the front pages, most of the rest of the world really doesn't care. There are no geopolitical interests in Burma. It has some natural gas and oil, but not enough to lead to international gamesmanship or posturing. Just as important, when the world does wake up to the chronic human rights disaster facing Burma's people, or a humanitarian disaster such as Cyclone Nargis, China is there to block concerted international action.

Indeed, even to float a UN security council resolution is to run into a Chinese veto. In January 2007, for instance, China (and Russia, in the hope of Chinese solidarity on Kosovo) vetoed a US and UK resolution demanding action on human rights. After the September uprising in Burma it made it clear it would continue to exercise its veto.

China's foreign policy is predicated on an outdated notion of national sovereignty, that what happens in Burma or China stays in Burma or China. But things are changing: just look at the Chinese government's response to its own horrific disaster in Sichuan. Since the earthquake, it has mobilized its entire governmental machinery and accepted foreign aid to help victims. This is unprecedented and a reflection of the global information society that doesn't allow reality to be airbrushed out of the picture any longer.

Britain has had a largely exemplary record on Burma in recent years. Gordon Brown and David Miliband have made strong public statements. But it must now be careful not to play into the hands of the generals. Britain has tried to smuggle humanitarian assistance into Burma using ASEAN as if it were a Trojan Horse. But in agreeing to an ASEAN-led mechanism, the SPDC is most likely just playing the international community off against one another and playing for time. While ASEAN relief is welcome, Britain and others must remember that ASEAN is a club largely made up of autocracies and dictatorships and has always, in the end, protected Burma, saying it would deal with its rogue member from inside the ‘ASEAN family'.

For the past 20 years, the Burmese military's brutal diplomatic brinksmanship has led to the same result every time. The agent of ‘breakthrough' - in this case, ASEAN - receives kudos for diplomatic negotiating skills, the generals look magnanimous and receive a brief honeymoon full of optimism that they have changed, and then hopes are sunk as the regime delivers nothing. And the Burmese people keep on suffering.

Brad Adams is Asia division director at Human Rights Watch, based in London. More information about Human Rights Watch’s work on Burma can be found here.