Israel should declare an immediate moratorium on demolitions of Bedouin homes and create an independent commission to investigate pervasive land and housing discrimination against its Bedouin citizens in the Negev, Human Rights Watch said in a new report released today.

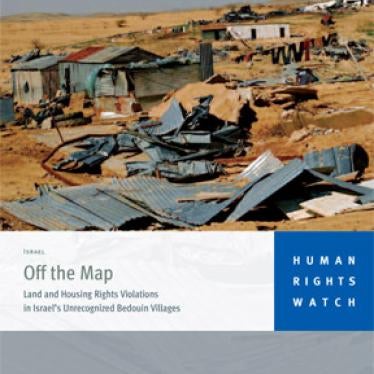

The 130-page report, “Off the Map: Land and Housing Rights Violations in Israel’s Unrecognized Bedouin Villages,” documents how discriminatory Israeli laws and practices force tens of thousands of Bedouin in the south of Israel to live in “unrecognized” shanty towns where they are under constant threat of seeing their homes demolished and their communities torn apart.

Human Rights Watch based its findings on interviews conducted in 13 unrecognized Bedouin villages and three government-planned Bedouin townships in the Negev. It interviewed dozens of Bedouin residents, as well as activists, community organizations, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), academics, and lawyers in Israel. Human Rights Watch submitted a detailed letter to the government in 2007 with preliminary findings and questions, and incorporated relevant information from the Ministry of Justice’s response into the report.

“Israeli policies have put the Bedouin in a lose-lose situation,” said Joe Stork, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “The state has forced them off the land they claimed as their own and into illegal shanty towns, cut off from basic necessities like water and electricity.”

Israel has demolished thousands of Negev Bedouin homes since the 1970s, and hundreds in 2007 alone. Authorities say that 45,000 existing Bedouin homes in approximately 39 “unrecognized” villages were built illegally and thus potential targets for demolition. Israeli officials contend that they are simply enforcing zoning and building codes. But Human Rights Watch found that officials systematically demolish Bedouin homes while often overlooking or retroactively legalizing unlawful construction by Jewish citizens.

While the Bedouin suffer an acute need for adequate housing and for new (or recognized) residential communities, the state instead is developing new homes and communities for Jewish citizens even though some of the more than 100 existing Jewish communities in the Negev sit half-empty. In theory, any citizen can apply to live in these Negev communities, but in practice selection committees screen applicants and accept people based on undefined notions of “suitability” that systematically exclude Bedouin.

“Israel is willing and able to build new Negev towns for Jewish Israelis seeking a rural way of life, but not for the people who have lived and worked this land for generations,” Stork said. “This is grossly unfair.”

Israeli officials insist that Bedouin can relocate to seven existing government-planned townships or a handful of newly recognized villages. Human Rights Watch found that the government-planned townships constitute seven of the eight poorest communities in Israel and are ill-equipped to handle any influx of residents. Most Bedouin reject the idea of relocating to the townships, with their deplorable infrastructure, high crime rates, scarce job opportunities, and insufficient land for traditional livelihoods such as herding and grazing. In addition, the state requires Bedouin who move to the townships to renounce their ancestral land claims – unthinkable for most Bedouin who have claims to land passed down from parent to child over generations.

The state controls 93 percent of the land in Israel, and a government agency, the Israel Land Administration (ILA), manages and allocates this land. No Israeli law requires the ILA to ensure fair and just distribution of land. Almost half its governing body are members of the Jewish National Fund, which has an explicit mandate to develop land for Jewish use only. Today, the Bedouin community comprises 25 percent of the population of the northern Negev, but controls less than 2 percent of the land there.

Authorities have allocated large tracts of land and public funds for family ranches or farms. The state connects these farms to national electric and water grids despite the fact that some lack proper planning permits and retroactively legalizes them rather than demolish them.

“The hypocrisy in the policy towards these large individual farms is not lost on the Bedouin,” said Stork. “The state’s claims that the Bedouin villages are too dispersed to receive state utilities don’t seem to matter when it comes to the farms.”

In October 2007, the Ministry of Housing appointed a commission headed by former state comptroller and retired Supreme Court Justice Eliezer Goldberg to examine the land-ownership dispute between the state and the Bedouin community in the Negev. The eight-member Goldberg Commission, which does not include a representative from the unrecognized Bedouin villages, began work in January 2008, proposing to publish its findings and recommendations within six months.

Human Rights Watch urged the commission to base its recommendations on Israel’s international human rights obligations prohibiting discrimination and guaranteeing rights to adequate and secure housing, and protection from forced evictions.

“One recommendation should be for a special commission that can conduct an impartial and comprehensive examination of the problem of the unrecognized villages,” Stork said. “Because the state itself is responsible for this systematic discrimination and denial of basic rights, an independent investigative body is needed.”

Many Bedouin told Human Rights Watch about the devastating impact of home demolitions on their families. The authorities typically demolished the homes without specific advanced warning, often leaving families with nothing more than a tent for shelter.

Testimonies

Sarah Kishkher of Um Mitnan told Human Rights Watch what this meant. “Everything used to be so clean and neat. We could keep the home organized – we had cupboards to fold the children’s clothes and keep them in. We could bathe the children whenever we wanted. Everything [in a tent] is in this sandy dirt. We can’t keep food for the baby in a fridge. We have lost everything.”

Some Bedouin have seen their homes destroyed more than once. Fatima al-Ghanami, a 60-year-old widow in Um Mitnan, suffers from diabetes. Officials demolished her home several years ago. Shortly after she rebuilt, she received another demolition warning order. “When I got the demolition order for the old house, I was sure they would never come. Now I know better. I know they’ll come and do it. … They might come tomorrow, they might come anytime. If they demolish this place, I have nowhere to go and no money left. I have no idea what I’ll do.”

Background

Some Bedouin villages pre-date the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, while others sprang up after Israel forcibly displaced the Bedouin from ancestral lands in the early days of the state. Israel passed laws in the 1950s and 1960s enabling the government to lay claim to large areas of the Negev where the Bedouin had formerly owned or used the land. Planning authorities ignored the existence of Bedouin villages when they created Israel’s first master plan in the late 1960s, embedding discrimination in policies that continue today, some 40 years later.

According to the United Nations committee responsible for interpreting the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which Israel ratified in 1991, governments can carry out forced evictions only in “the most exceptional circumstances,” and in accordance with international law. Even in exceptional circumstances, human rights principles require that the government must consult with the affected individuals or communities, identify a clear public interest requiring the eviction, ensure that those affected have a meaningful opportunity to challenge the eviction, and provide appropriate compensation and adequate alternative land and housing arrangements.

In almost all cases, Human Rights Watch found that the state met none of these criteria.

In the unrecognized villages of Um al-Hieran and Atir, near the Yatir forest, the state filed lawsuits to evacuate and expel the approximately 1,500 residents in April 2004. In September 2006, the state obtained approximately 40 judicial demolition orders against almost all the houses in Um al-Hieran, and in June 2007 the ILA demolished 25 of those homes. Um al-Hieran dates from 1956, when the government moved the residents from their land in the western Negev, around today’s Kibbutz Shoval. Now the government wants the land of Um al-Hieran to construct a larger Jewish settlement, Hiran. The government never informed Um al-Hieran’s residents of its plans or invited them to be a part of the new community before attempting to displace them forcibly again.

After planning officials distributed demolition warnings or orders on all the homes in the village of al-Sira in September 2006, village residents approached the authorities but found there were no alternatives envisaged for the community. Resident Khalil al-Amour told Human Rights Watch: “They always say ‘maybe’. Maybe you’ll get a neighborhood when [the township of] Rahat expands; maybe you can go to the [newly planned] township of Marit which does not even exist yet. We are invisible people to them, so perhaps we can live in invisible houses.” All the homes in the village now have demolition orders.

The Human Rights Watch report discusses examples of countries where governments have attempted to address indigenous land claims and provide redress where there have been historical injustices. New Zealand, Canada, and Australia, for instance, have established national processes, ranging from commissions to tribunals, and in some cases these have resulted in returning land which was owned or traditionally used by indigenous populations to their control.