The trial of David Hicks, the 31-year-old Australian charged with providing material support for terrorism, should be moved to US federal court.

Under the system of military commissions previously established by President George W. Bush, Hicks had been charged with conspiracy to commit war crimes, attempted murder, and aiding the enemy. Those charges were dropped when the Supreme Court struck down the commissions in June 2006. Now Hicks is charged with a single count of providing material support for terrorism – an offense that does not violate the laws of war and that should be tried in federal court.

“The Department of Justice has successfully prosecuted dozens of cases of material support for terrorism since 9/11,” said Jennifer Daskal, US advocate for Human Rights Watch. “Federal court, not fundamentally flawed military commissions, is where Hicks belongs.”

Of particular concern are commission rules that allow the use of evidence obtained through abusive interrogation techniques prior to January 2006. These rules are compounded by provisions that allow interrogation methods and activities to be protected from disclosure, even to defense counsel and even for the purposes of challenging the use of evidence obtained by torture.

The administration has, in other proceedings, taken the surreal position that descriptions of abuse constitute top-secret information, and there is a strong likelihood that it will take the same position in here as well. If the military judge agrees, Hicks’ lawyers could be prevented from learning the circumstances under which any statements used against him were made – making it virtually impossible to challenge the use of such evidence as being the result of torture or abuse.

Human Rights Watch expects such abuse questions to be front and center in the Hicks case. Hicks has alleged that he was sodomized, beaten, and subject to forced injections while in US custody. In a court filing, he claims that he became so fearful of further interrogation that he decided to “cooperate,” realizing that if he “pleased” the interrogators he could avoid further abuse. The use of coercive methods, alleged by other detainees as well, creates the possibility that detainees who wanted to make the abuse stop may have made false confessions and false accusations.

“Absent a change in policy, Hicks’ trial may be best remembered most for the administration’s use of coerced evidence and its continued attempt to prevent allegations of abuse from coming to light,” said Daskal.

Of additional concern, Hicks is being tried under a newly defined crime of material support of terrorism that was adopted as part of the Military Commissions Act of 2006 and carries a possible penalty of life imprisonment. By comparison, the only analogous federal crime that existed at the time that Hicks is alleged to have engaged in prohibited conduct – from December 2000 to December 2001 – carries a maximum penalty of 15 years. This retroactive application of a newly enacted criminal sanction is expected to be the subject of legal challenge by Hicks’ defense attorneys.

“It seems that the administration would rather open itself up to a whole new round of legal challenges than provide Hicks an open and fair hearing in federal court,” said Daskal.

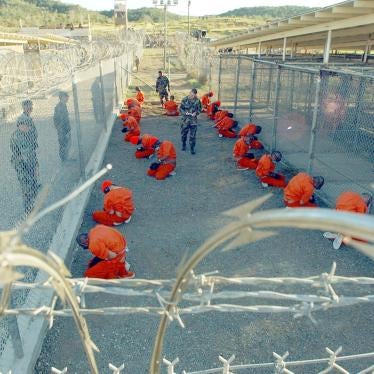

While Hicks is the first detainee to be formally charged by the military commissions, charges against two others, Salim Ahmad Hamdan and Omar Khadr, have been sent to the presiding judge for review, but not yet approved. The administration has stated that it ultimately plans to try between 20 and 70 detainees under these commissions. Even if all 70 cases go forward, it would still leave more than 300 detainees held without charge at Guantanamo Bay, and without access to an independent court to contest their indefinite detention.

Although these detainees are all labeled “combatants” by the Bush administration, most of those detained in Guantanamo Bay were picked up far from any battlefield. According to the Pentagon’s own records, the US has not even accused the vast majority of them of carrying a weapon or fighting US or coalition forces. Hundreds of detainees were sold to the US by bounty hunters or turned over by rival clan members, while many high-level Taliban and al-Qaeda operatives with the resources to buy their freedom got away.