(Johannesburg) - South African health care professionals are endangering the health of the country's large foreign population by routinely denying health care and treatment to thousands of asylum seekers, refugees, and migrants, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. South Africa's foreign-born residents, who are particularly vulnerable to disease and injury, face xenophobic violence as well as systematic discrimination in obtaining basic care.

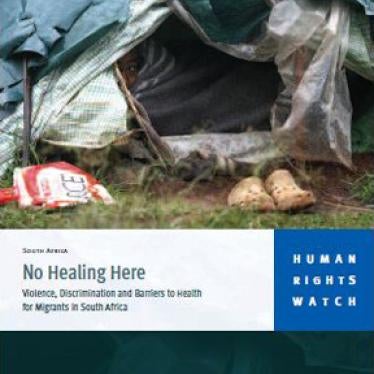

The 89-page report, "No Healing Here: Violence, Discrimination and Barriers to Health for Migrants in South Africa," describes how harassment, lack of documentation, and the credible fear of deportation prevent many newcomers from seeking medical treatment even though South African law and policy state that asylum seekers, refugees, and migrants have a right to care. Those who do seek treatment are often mistreated and verbally abused by health care workers and denied care or charged unlawful fees.

"Migrants to South Africa are abused in transit, attacked upon arrival, and then denied care when they are injured or ill," said Rebecca Shaeffer, fellow in the health and human rights division of Human Rights Watch. "The South African government should be ensuring that these people get the care they need, and are entitled to, under the country's constitution."

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 100 migrants, health care workers, and advocates to produce the report. Migrants who crossed the border from Zimbabwe, for example, told Human Rights Watch that they find it difficult to get health care because they lack documentation, basic information, and financial resources. Rape survivors said they are required to file police reports before they get emergency medical treatment, but are they are too fearful of deportation to follow this procedure.

The South African Department of Health has affirmed the rights of asylum seekers and refugees to obtain care, but Human Rights Watch found that health care workers repeatedly violated that provision and discriminated against patients on the basis of their nationality or lack of proper documentation. According to the report, permanent disabilities resulting from xenophobic violence against migrants are being compounded by xenophobic discrimination in health care settings.

Furthermore, in urban centers throughout the country, refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants are often placed in unsafe temporary shelters, resulting in increased risk of infectious disease transmission, interruption of treatment for chronic illness, and often inadequate nutrition.

The delayed, interrupted, or denied treatment of migrant health threatens to further strain South Africa's already stretched health system. When untreated, illness becomes more severe or resistant to first-line drugs, preventable disability develops, care becomes more costly, and communicable diseases threaten citizens and non-citizens alike.

"Discrimination against foreigners is institutionalized in South Africa's health care system," Shaeffer said. "People seeking care should not be subjected to abuse."

Improving all of the conditions that contribute to poor health conditions for migrants will require the collaboration of numerous government agencies, Human Rights Watch said. The report recommends four categories of reforms to improve the situation:

- Protection from deportation: The Department of Home Affairs should implement the planned special dispensation permit for Zimbabweans, easing the fear of deportation that serves as a major barrier to care for many undocumented migrants, especially Zimbabweans. The department should also ensure that asylum seekers, refugees, and Zimbabwean migrants are not subject to arbitrary or extra-legal arrest and deportation.

- Protection from attacks: South African Police Service should enhance protection for migrants from opportunistic criminal violence near the Zimbabwean border and from xenophobic violence throughout South Africa. Police should also ensure that rape survivors are not forced to contact the police before receiving life-saving medical attention.

- Protection from discrimination: The Department of Health should enforce its equal access policies through improved training, reporting, and accountability measures. It should also develop prevention and treatment programs for mobile and migrant populations, providing improved access to health and rights-related information, as well as cross-border treatment initiatives.

- Better information: The government should improve its data collection concerning the number of migrants in South Africa, their health needs, and the costs of their care. Budgets and planning should be responsive to needs on the ground, and providers that serve a high number of informal migrants should get the support they need.

"The South African health system is strained trying to meet the needs of all of its residents, but discriminating against migrants is not the way to balance budgets." Shaeffer said.

Testimony from refugees and asylum seekers:

"Xenophobia is still here - only now it lives at the hospital." - Sefu, a refugee displaced by xenophobic violence who was turned away for care at Johannesburg General Hospital.

"I was robbed [and] assaulted. People on the street just watched it happen. I went to Hillbrow clinic. I asked for an x-ray but they said, ‘No, that's not for foreigners. Go back to Zimbabwe if you want x-rays.' I went back four times but it was always, ‘No, my friend. That's for South Africans.'" - Trevor, an asylum seeker in Johannesburg.

"At the hospital they told me, ‘This is not your country, we can't treat you,' and sent me away. I left the hospital and went to another clinic. One doctor, a female doctor, was saying, ‘Just treat him,' but some others were saying, ‘Don't treat him.' Some of them said I was a human being and deserved treatment, and others fought her right in front of me." - Said, Somali refugee displaced by xenophobic violence.

"I went to Joburg Hospital because I felt like I had TB. I was coughing and losing weight. They told me to go to Hillbrow. At Hillbrow they said, ‘We don't like foreigners; you are thieves.' I heard some of the nurses saying ‘We don't like them here. This hospital is for South Africans.'" - Kelvin, Zimbabwean asylum seeker in Johannesburg.

"It's true that everyone gets treated badly in the public hospitals, but it's worse for non-nationals. Foreigners wait even longer than we do. Health care worker attitudes are a problem. They get annoyed with language problems, and they don't seem willing to assist. Most clinics don't have interpreters, so the doctors will just ask yes or no questions, and don't get to the bottom of things. They take advantage of foreigners' lack of knowledge of their rights, so they will tell them go somewhere else." - Eva, South African citizen married to Congolese refugee.