(纽约)-人权观察今天表示,不丹皇家政府应撤销数十名政治犯的定罪并予释放。这些政治犯据称遭受酷刑,并因不公正审判入狱数十年。

这些和平的政治、反歧视和其他社会运动人士以危害国家安全罪名被捕,并由不丹司法机关定罪判处重刑。相关案件均早于2008年,在不丹由绝对君主制转为君主立宪制之前发生。目前尚在狱中者皆背负重刑,包括终身监禁。不丹社运人士呼吁旺楚克国王特赦这些囚犯。

“不丹公开宣扬的‘国民幸福总值’原则并未顾及这群被不当定罪而在狱中度过数十寒暑的政治犯,” 人权观察南亚区主任米纳克希・甘古利(Meenakshi Ganguly)说。“不丹当局应正视漫长刑期对这些囚犯及其家属造成的伤害,并予以紧急补救。”

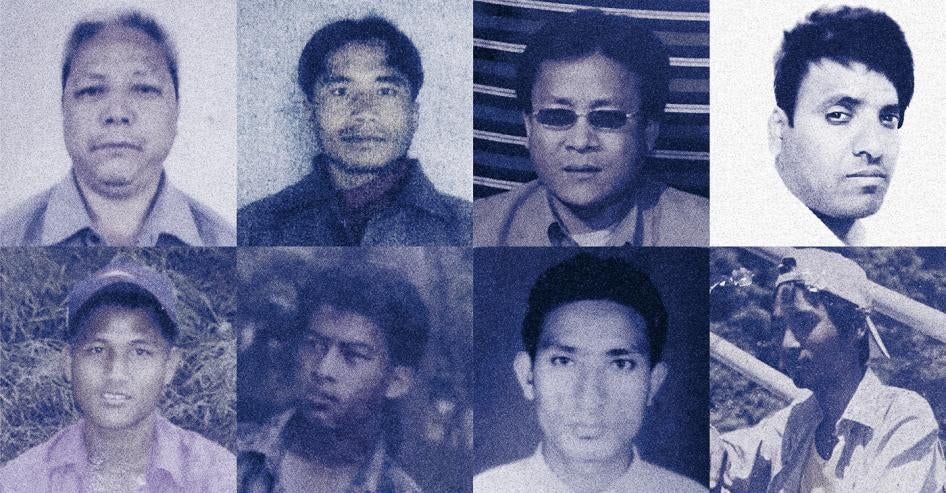

不丹政治犯人数迄今不明,人权观察目前收集到37名仍在服刑囚犯的资料,其初次被捕时间介于1990年至2010年之间。他们大多与一般囚犯分开关押,条件极差,当中许多人患有生理或心理疾病,而且被禁止与家属定期通信。

这些官方认定为“政治犯”的受刑人,大多是以严厉且措词含糊的1992年《国家安全法》定罪。按照不丹法律,“凡阴谋、计画、教唆、煽动或着手颠覆三元素(Tsa-Wa-Sum,意指国王、国家和人民)而被定罪者”即为政治犯。人权观察找到37件个案,主要都是以这项罪名判刑,其中至少24人被判处无期徒刑不得假释,其余囚犯刑期介于15到43 年。

这群人中的大多数——32 名囚犯——来自不丹境内操尼泊尔语的洛昌人(Lhotshampa,意为“南方人”)社群,数十年来持续遭受不丹政府的歧视和虐待。 1990年代初期,由于法律歧视、公民权争议以及不丹安全部队普遍滥权所引发的危机,迫使逾9万名洛昌人逃往尼泊尔避难。如今这些难民大多已获美国、加拿大和澳大利亚收容安置。

其余5名囚犯属于沙乔普人( Sharchop,意为“东方人”)社群。这四男一女因涉嫌联系被查禁的不丹国民大会党(Druk National Congress)而被捕,该党倡导议会民主制和人权保障。

据出狱和在押囚犯及其亲属表示,被捕人士遭到当局刑求逼供和体罚,而且在审判时没有律师辩护。一名被判叛国和恐怖活动罪的囚犯说:“因为(羁押期间)无情的肉体折磨,我们没有选择,只能按照他们(安全部队)的要求和他们的说词向法庭认罪。然后由地方法院将我们判处无期徒刑。我们从未得到任何法律辩护。”

许多囚犯家属表示,他们至今没有拿到任何官方文件,不知道他们的亲属为何被定罪。出狱囚犯有时也无法用白话或法律名词解释自己因为什么罪名被判处重刑。

不丹社运人士向人权观察表示,尽管从2008年就已开始推动法制现代化,至今仍然没有任何人权组织在国内运作,传媒也避免报导当局认为敏感的话题。因此,政治犯及其悲惨处境很难获得公众关注。

在人权观察确认的32名洛昌人政治犯中,有15人是在1990年代以后因为抗议族群迫害而被捕判刑。其中8人曾为不丹皇家陆军士兵,因涉嫌参与族群抗争而被控叛国罪。然而,家属和已出狱囚犯都无法提供任何有关起诉或判决的司法文书。

据社运人士消息,丹巴・辛・普拉米(Dambar Singh Pulami)在2001年从尼泊尔难民营返回不丹“查看家产”时被捕,后以“勒索、绑架、谋杀和颠覆活动”判刑43年,并因身患重病于2022年5月入院治疗。

自2008年以来,在一群1990年代初期随长辈逃离的年轻难民返回不丹之后,又有15名洛昌人被捕。不丹当局声称这些年轻人意图加入由非法的不丹共产党所领导、争取难民返国和少数人权利的武装抗争。

他们大多刚刚返国就被抓捕,有些人身上带着小型武器,另一些人带着政治宣传品。法庭档案显示,检方认为这群人的难民身分表示他们已经 “背弃国家,决心与不丹为敌”。他们最终以“叛国罪”和“恐怖活动罪”判处无期徒刑,其中12人仍在服刑。

在2008年的案件中,另有三名洛昌人本身并非难民,但被控支援前述返国难民。还有一人在2010年被捕,也被列入同案判处无期徒刑。人权观察检视相关法庭档案发现,此案在程序上未达基本的公正审判标准。

已知37名政治犯中,25人被关在首都廷布附近的成冈(Chemgang)中央监狱专门关押 “政治犯”的监区。据受刑人指出,虽然监狱条件在1994至2012年国际红十字会定期访视期间稍有改善,近年又有所下降。狱中的食品和衣物供应皆有不足。

包括前士兵在内的另外10名政治犯被关在拉布纳(Rabuna)地区的偏远隐秘设施,极少数由此获释的前囚犯之一形容该处“有去无回”。还有2名政治犯,人权观察无法确认他们的关押地点。

据部分囚犯或其亲属报导,受刑人持续忍受严重健康问题,尤其是酷刑后遗症。患病囚犯无法在狱中得到充分治疗,一些出狱囚犯表示可能有两人因此丧生。

人权观察于2022年11月7日就本报告所载资讯和指控致函不丹政府,未获任何答覆。

不丹国王依法有权实施特赦。前任国王曾于1999年特赦40名政治犯,包括部分无期徒刑受刑人。 2022年,现任旺楚克国王也曾特赦一名无期徒刑政治犯。

联合国、各捐助国和有关政府应敦促不丹当局无条件释放政治犯和其他因行使基本人权或因违反正当程序审判而被监禁的人。政府应大幅改革法律体系以符合国际人权法,采取措施终止酷刑并为受害者提供补救,并允许对监狱条件进行独立监测。

“对政治犯的长期监禁和虐待仍是不丹人权记录的一大污点,” 甘古利说。“不丹当局应该释放这些囚犯,并着手改革以禁绝拘留期间的酷刑、不公正审判和恶劣的监狱条件。”

相关情况和调查结果详见下文(仅有英文版)。

Political Prisoners in Bhutan: A History of Discrimination

The population of Bhutan includes three communities that have different religious traditions and ethnic origins, and traditionally speak different languages.

The politically and culturally dominant Ngalop, who are traditionally concentrated in the central and western regions, speak Dzongkha and mostly follow Tibetan Buddhism. The royal Wangchuk dynasty belongs to the Ngalop community and became hereditary kings of Bhutan in 1907. The current king, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, came to the throne following the abdication of his father, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, in 2008 – the same year that Bhutan adopted parliamentary democracy under constitutional monarchy.

The Sharchhops, concentrated in eastern Bhutan, are descendants of early migrants from Tibet to what is now Bhutan. They traditionally speak Tshangla, and many of them practice Tibetan Buddhism. Some of them joined a campaign for political democracy in the 1990s by the now banned Druk National Congress.

The Nepali-speaking community, known as Lhotshampas, migrated to Bhutan in the 19th century and settled in the then largely uninhabited southern part of the country. Lhotshampas are predominantly Hindu. By the late 1970s the Ngalop establishment had come to see this population as a threat to Bhutan’s cultural identity and to their own dominant position. The government introduced a series of discriminatory citizenship laws, stripping many Lhotshampas of their citizenship, as well as “Bhutanization” laws aimed at enforcing a version of national identity based on Ngalop culture and language.

Protests against these policies broke out in 1990. The police arrested thousands of people who were accused of taking part in the protests, which the government deemed anti-national. Many were tortured and ill-treated. By late 1990, Nepali speakers began to flee Bhutan and within two years about 90,000 Bhutanese refugees were in camps in Nepal. Over the ensuing two decades this population expanded. Between 2008 and 2015, over 100,000 Bhutanese refugees who had been living in the camps in Nepal were resettled in third countries, primarily the United States, Canada, and Australia.

Primarily in the 1990s, but up until 2008, the Bhutanese authorities arrested and prosecuted dozens of people for their alleged participation in protests and other alleged “national security” offenses. Many remain imprisoned.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch was able to identify 37 political prisoners still in prison in Bhutan. Between April and December 2022, Human Rights Watch interviewed 11 former political prisoners and 8 relatives of current prisoners, as well as exiled activists who were able to confirm the identities of those in prison.

Under Bhutan’s 2009 Prison Act, political prisoners are supposed to be held at Chemgang prison and separated from other prisoners. However, Bhutanese authorities provide no information on current political prisoners, and except for a UN working group visit in 2019, there have been no independent inquiries into the prison population. As a result, the Human Rights Watch figure may be an undercount.

Human Rights Watch carried out some interviews with the assistance of the Global Campaign for the Release of Political Prisoners in Bhutan. Human Rights Watch also interviewed former prisoners, witnesses, and relatives of prisoners in the Beldangi refugee camp in Nepal.

All interviews were conducted in English or in Nepali, without financial compensation or other incentives. Some interviewees requested anonymity for security reasons.

Torture

Current and former inmates alleged that the authorities routinely used torture and other ill-treatment to compel detainees to confess to actions that they denied, to make their statements at trial correspond to the prosecution’s allegations or the testimony of other defendants or witnesses, or as a form of punishment.

One prisoner described torture by Bhutanese soldiers after his arrest in 2008:

They [Bhutanese soldiers] arrested us and took us to their barrack, and for 20 days they treated us mercilessly. They used to tie us, and using cane sticks they would beat us continuously on our entire body, but particularly on the bottom of our feet. They beat us so much on our feet they became senseless after a while. They also immersed us in ice cold water. After that they tied our hands and legs for nearly seven days. After seven days they finally gave us some fried corn. They didn’t even allow us to sleep. After that, they prepared a statement as per their own wish and thought, not based on what we said.

The coerced “evidence” was then used at their trial.

They brought us to the district court. The judge asked us, “Do you have anything to say?” So we gave them our statement in writing. But there was no use of that submission. They used their own statements instead.

Those arrested in the 1990s experienced some of the worst abuse. Former prisoners said that during that period torture methods commonly used included chepuwa, which involved crushing the thighs between pieces of wood; beating prisoners then putting them in a sack and taking them away in a vehicle, creating the fear of extrajudicial execution; and the use of stress positions and barbed wire that would leave the prisoner bloody as their strength failed.

“For three years I couldn’t change my clothes, or wash my hands or face,” said Mangal Dhwoj Subba, a former political prisoner who was detained from 1990 to 1998. “They would beat me up, so I confessed, although it wasn’t true.”

Another former political prisoner, Dil Kumar Rai, said that during his interrogation, police and soldiers jumped on his chest, causing pain that recurred for six or seven years. He was shown instruments used for torture including sticks and an electric iron, and believed that detainees were sometimes extrajudicially executed, so he made a confession.

Man Bahadur Rai, a former political prisoner, said that as a 16-year-old, he had participated in the 1990 protests, and later became a refugee in Nepal along with his family. He returned to Bhutan in 1996 for a personal visit and was arrested. He said that during six months in police custody his hands were continually handcuffed except when he was eating, and he was beaten with “whatever they could find,” especially when he refused to admit to things he had not done. Nevertheless, he confessed only to acts of disorder during the 1990 protests in which he said he did participate, and was sentenced to 21 years in prison.

A political prisoner imprisoned from 2006 to 2014 said that during his first six months in army custody he was beaten while being interrogated in a language he couldn’t understand. If he became unconscious during the torture, he said, the soldiers revived him with cold water.

A prisoner who was jailed in 2008 said:

They took me to the local police station. They tortured me for almost two weeks before starting the legal process. Once it [the case] was registered to a court it took five months for trial, and I was tortured quite severely when my statements didn’t match [those of the prosecution]. They used wooden batons. I was handcuffed in front of my body and told to squat on the ground. A soldier would put his leg between my cuffed hands then beat me on the back.

These accounts are consistent with those of the family members of prisoners who remain in prison. “He was tortured,” said the wife of a prisoner who was arrested and convicted in 2008. “I saw his body covered with marks from beating on his back.”

“He was tortured by the army,” said the sister of another prisoner who was arrested in 2008 and remains in prison. “They [the prisoners] were beaten and burned. When I met him, he was very sad, his eyes were full of tears.”

The mother of a man who had been imprisoned since 2008 said she had seen scars on his wrists from being tightly bound for six months and that he said he had been severely beaten, given food mixed with dirt, and locked in a small toilet room for an extended period. The sister of another man who has been in prison since 2008 said her brother is now deaf in one ear because of the beatings he received during his first six months in custody.

Violations of Fair Trial Rights

In 2019, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention interviewed several people then imprisoned under national security legislation. The Working Group found “a number of due process violations when the individuals had been tried some 25 years ago. The Working Group is aware that, at the time, there were no legal practitioners in the country.”

There were no defense lawyers to represent the accused during the period these prisoners were put on trial. All the prisoners Human Rights Watch interviewed said that they and their co-defendants had represented themselves, and that all the lawyers involved in their trial acted on behalf of the government. Former prisoners said that they were produced in court and asked to confirm prosecution statements that had been coerced under torture.

A prisoner who was convicted of national security offenses in the early 1990s called his trial a “farce,” saying, “They forced me to confess to false charges.” Another prisoner, convicted in the early 1990s and sentenced to 24 years in prison on charges he denies, said that police would “torture people when they came back from court in the evening if they denied charges. So out of fear we would confess.… There wasn’t a system with lawyers.”

Former prisoners were sometimes unable to describe the offense for which they had served long sentences, in recognizable or specific legal terms. Similarly, families of serving prisoners said that they have not been provided with any official documentation.

Access to an attorney of one’s choosing and adequate time and resources to prepare a defense are fundamental to the right to a fair trial. Several prisoners who were compelled to represent themselves appeared to have little understanding of court procedure. One said that at the end of his trial he signed the court’s verdict although he was unable to read it and did not know what it said.

A prisoner interviewed by the UN Working Group in 2019 told Human Rights Watch:

We could not talk to them [members of the Working Group] openly. The prison officers came and threatened us before the meeting saying, “Look, you have to live with us. They will leave tomorrow, so think wisely before speaking.” … We did sit with the UN arbitrary detentions team during the meeting, but we were too scared to speak openly about realities and show them the true picture.

Prison Conditions

Twenty-five political prisoners are held in a dedicated block at Chemgang Central Prison. Ten other political prisoners are at Rabuna, a secretive facility used to imprison former soldiers and government officials accused of treason, but information on conditions there or at other prisons where political prisoners may be held is not available.

Prisoners said that their segregated block at Chemgang consists of about 16 cells arranged around an outdoor area. Six cells have toilets while 10 have buckets for that purpose. Prisoners are locked inside their cells from 5 p.m. to 7 a.m. Bedding, including bed covers, is at times completely inadequate in the generally cold climate.

Several said they suffered severe and persistent mental health problems due to the conditions. One woman said that she had found her brother unwell when the family had visited him at Chemgang and had offered to bring medicines. “Police take relatives’ [telephone] numbers and say, ‘We’ll contact you if he gets sick,’ but they never do,” she said.

In 1994, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) began visiting prisoners held under national security laws in Bhutan. Former prisoners said that there was a significant improvement in political prisoner welfare at Chemgang after the ICRC’s visits but that the conditions declined since the visits ended in 2012.

Many prisoners said that the conditions had worsened in the past year. Information obtained by Human Rights Watch in March 2022 indicated that the prison authorities “have made cuts to the food supplies as compared to before.” Another source said, “They have almost stopped giving any clothes to the prisoners. It is very cold. We used to get firewood during the winter but that has been reduced.”

A current prisoner told his brother about bad conditions in 2022. “Supplies are low,” the brother said. “They have insufficient food. There are no new blankets or mattresses.”

Prisoners are prevented from making or receiving telephone calls to Nepal or other countries where refugees have resettled. Prisoners are also prevented from sending letters, and their families do not know whether the letters they send are delivered. The lack of communication causes anguish to both the prisoners and their families.

Although family visits to inmates were impossible due to the Covid-19 pandemic, when Bhutan closed its borders, the families sometimes received information through prisoners who were allowed to make brief telephone calls to relatives in Bhutan.

In late 2022, humanitarian agencies resumed the process of attempting to arrange family visits with prisoners. However, some refugee families who have resettled as far away as Australia, Canada, or the United States have not been able to make any contact with their imprisoned relatives for years. A currently serving prisoner said he and other prisoners have fallen completely out of contact with their families: “We have no idea. We knew they were in Nepal before. We used to receive letters and even send some letters through the Red Cross, but now even that has stopped.”

Three refugee families chose not to be relocated to a third country, remaining in the now sparsely populated Beldangi refugee camp in Nepal to be closer to their relative imprisoned in Bhutan. “I can’t leave without my son,” said Dambar Kumari Adhikari, the mother of Om Nath Adhikari, a political prisoner. “When we go to see them they seem hopeful that maybe they’ll get released soon. That’s the reason we haven’t left, we’re waiting for them.”

Domestic Legal Standards

Bhutan was an absolute monarchy until 2008, when it adopted a new constitution defining the kingdom as “a democratic constitutional monarchy.” The constitution declares that “[t]he State shall strive to promote those conditions that will enable the pursuit of Gross National Happiness.” Among the internationally recognized human rights protected by constitutional provisions are nondiscrimination and equality before the law, fair trials, and the prohibition of torture.

Bhutan’s legal system is guided by Buddhist principles emphasizing concepts such as “compassion.” Bhutan is not a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights or the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, but it is bound by customary international human rights law as reflected in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Many political prisoners are held under Bhutan’s National Security Act (NSA) of 1992, which superseded the 1957 law. The NSA’s vague and overbroad provisions forbid treasonable acts against the Tsa-Wa-Sum (“king, people and country”). The law does not define “treasonable acts” or what would constitute “betrayal” or “harm to the national interest.”

Court papers relating to the national security trials that took place in 2008 show that, in addition to offenses under the NSA, defendants were also convicted of parallel offenses under the Penal Code. These include treason (article 327) and terrorism (article 329), which are first-degree felonies punishable by 15 years to life in prison (article 8). Defendants were also charged with possession of illegal weapons (articles 478 to 483). Bhutan abolished the death penalty in 2004.

A uniquely Bhutanese legal institution is kidu, which equates to concepts of “welfare” or “relief.” The king may grant kidu as well as “amnesty, pardon and reduction of sentences.” The Sentencing Guideline of Judiciary of Bhutan, 2022, states that an offender “sentenced to life in prison shall remain in prison until he or she dies or until pardoned or otherwise commuted to a fixed period, or receives Royal pardon, amnesty or clemency.” The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention concluded in 2019 that “those detainees serving life sentences have no prospect of release, with the exception of amnesty.”

Recommendations

To Bhutan:

- Quash the convictions and release political prisoners who were prosecuted for exercising their fundamental human rights and freedoms or were convicted on the basis of forced confessions and other serious fair trial violations.

- Provide prompt and adequate remedies to current and former prisoners who suffered torture and other ill-treatment in custody.

- Ensure that all prisoners get basic standards of care including food, adequate bedding, warm clothes, and medical treatment.

- Invite international humanitarian agencies to the prison system and give them full and unrestricted access to prisoners.

- Invite UN special procedures and other experts to advise on reforming the justice system and ensuring prisoner welfare.

- Review the National Security Act and amend it to comply with international standards on human rights protections.

To the United Nations, donors, and concerned governments:

- Raise human rights concerns, including the treatment of prisoners, in discussions with the Bhutan government.

- Publicly call upon Bhutan’s government to comply with fundamental international human rights standards, including the prohibition of torture and ill-treatment, fair trial standards, and the humane treatment of prisoners.

- Expedite the resettlement of released former prisoners to enable them to unite with their families, without regard to national security convictions in Bhutanese courts that did not meet international fair trial standards.