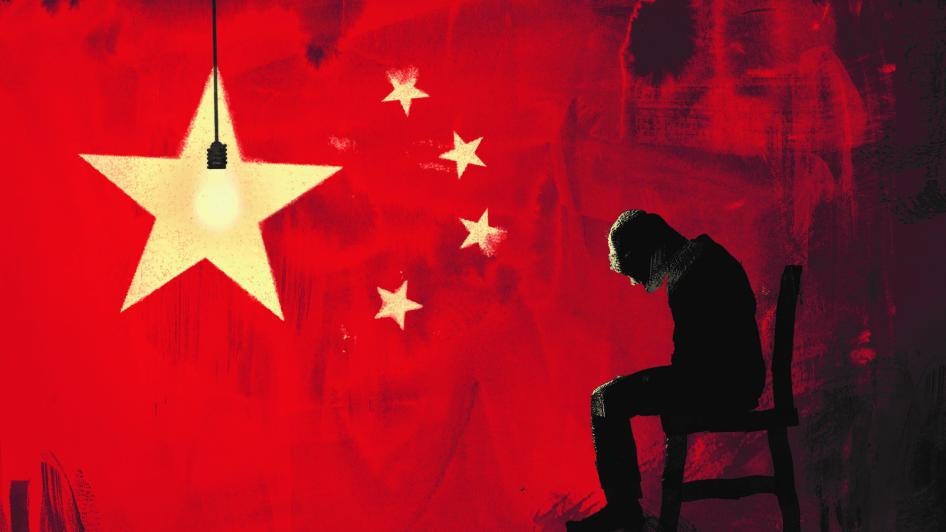

(Hong Kong) – The Chinese government should immediately abolish a secretive detention system used to coerce confessions from corruption suspects. The Communist Party-run system, known as shuanggui, has no basis under Chinese law but is a key component of President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign.

“President Xi has built his anti-corruption campaign on an abusive and illegal detention system,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch. “Torturing suspects to confess won’t bring an end to corruption, but will end any confidence in China’s judicial system.”

The 102-page report, “‘Special Measures’: Detention and Torture in Chinese Communist Party’s Shuanggui System,” details abuses against shuanggui detainees, including prolonged sleep deprivation, being forced into stress positions for extended periods of time, deprivation of water and food, and severe beatings. Detainees are also subject to solitary and incommunicado detention in unofficial detention facilities. After “confessing” to corruption, they are typically brought into the criminal justice system, convicted, and sentenced to often lengthy prison terms.

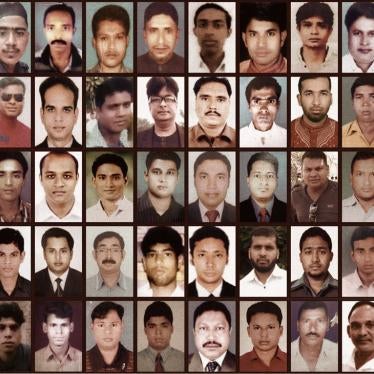

The report is based on 21 Human Rights Watch interviews with four former shuanggui detainees, as well as family members of detainees; 35 detailed accounts from detainees culled from over 200 Chinese media reports; and an analysis of 38 court verdicts from across the country. While there have been commentaries and analyses on the shuanggui system, the Human Rights Watch report is the first to contain firsthand accounts from detainees, as well as drawing on a wide variety of secondary, official sources.

The Chinese Communist Party’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) oversees the shuanggui system, to which all of the party’s 88 million members are subject. The CCDI and its lower-level offices, local Commissions for Discipline Inspection (CDIs), typically target government officials, but those detained also include bankers, university officials, and entertainment industry figures, among others. Bo Xilai, a former member of the party’s powerful Politburo, was reportedly held under shuanggui, where he said he confessed under “improper pressure” and was later sentenced to life in prison.

The start of a shuanggui investigation is often marked by an individual’s disappearance – family members are given no notification of the person’s detention or location, no information about the alleged infraction, or the length of detention. Detainees have no access to lawyers. Although there are time limits for shuanggui, CDI investigators can seek repeated extensions, permitting detainees to be held indefinitely, often until they confess. Shuanggui facilities are typically rooms in hostels with special features, such as padded walls or a lack of windows, to prevent suicides or escapes. Detainees are guarded round-the-clock by shifts of officials, often put together in an ad hoc fashion for this purpose, and subjected to interrogations by CDI officers.

A former shuanggui detainee told Human Rights Watch, “If you sit you have to sit for 12 hours straight, if you stand then you have to stand for 12 hours as well. My legs became swollen, and my buttocks were raw and started oozing pus.”

While President Xi has characterized the fight against corruption as a “matter of life and death” for the Communist Party, the same is true for shuanggui detainees: there have been at least 11 deaths in shuanggui custody reported by the media since 2010. In most cases, authorities claimed these were suicides, but family members often suspected mistreatment, and the lack of comprehensive, impartial investigations into these deaths deepens these suspicions. While former detainees reported that the harsh conditions in shuanggui prompted suicidal thoughts, they also said the constant surveillance and the room’s modifications, designed to prevent suicide attempts, made it difficult to put such thoughts into action.

Some CDIs, concerned about the reputational damage caused by deaths in custody, have partnered with hospitals and doctors to provide medical care for detainees whom the CDIs know will be subjected to torture and other ill-treatment.

CDIs are supposed to hand over evidence of crimes to the procuratorate, the state investigators and prosecutors who are responsible for investigating official crimes. Instead, Human Rights Watch found that procurators work together with CDI officers and participate directly in shuanggui. Such “joint investigations” extract confessions during shuanggui – where detainees have no procedural protections – and then use those confessions in formal legal proceedings. If in those proceedings detainees retract their confessions, claiming that they were made under duress, the procurators typically threaten to send them back to shuanggui. Judges commonly reject detainee objections in court on the grounds that shuanggui and its practices are outside of the scope of the judicial system.

“In shuanggui corruption cases, the courts function as rubber stamps, lending credibility to an utterly illegal Communist Party process,” Richardson said. “Shuanggui not only further undermines China’s judiciary – it makes a mockery of it.”

The shuanggui system has been a highly effective tool for Communist Party investigators: once they obtain a confession, there is little suspects can do to exonerate themselves. Acquittals are extremely rare, and, except in cases of detainee deaths, few investigators face punishments for abuses. Some interviewees told Human Rights Watch that those who tormented them and their families were promoted for their “effectiveness” in handling corruption cases.

China has a serious problem with corruption, but successfully combating it requires an independent judicial system, a free media, and robust protections for the rights of suspects, Human Rights Watch said. A crucial step is the abolition of shuanggui.

“Eradicating corruption won’t be possible so long as the shuanggui system exists,” Richardson said. “Every day this system threatens the lives of party members and underscores the abuses inherent in President Xi’s anti-corruption campaign.”