“Chinese authorities should move swiftly to dismantle this blatantly discriminatory passport system,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch. “The restrictions also violate freedom of belief by denying or limiting religious minorities’ ability to participate in pilgrimages outside China.”

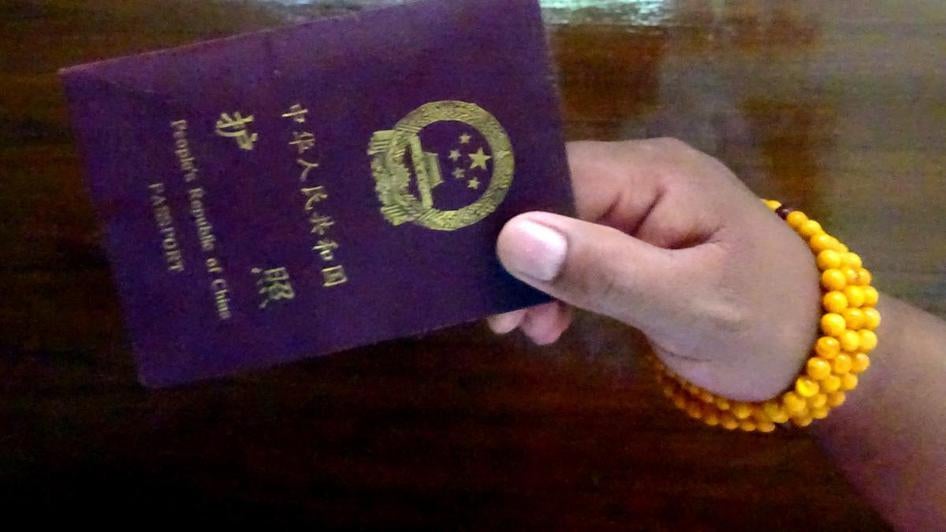

The 53 page report, “One Passport, Two Systems: China’s Restrictions on Foreign Travel by Tibetans and Others,” shows the evolution of a discriminatory two-track system for passports applications: a fast-track system is available in areas that are largely populated by the country’s ethnic Chinese majority, but only a slow-track system is allowed for those in most ethnic and religious minority areas. As of October 2014, less than 10 percent of prefecture-level administrations were still required to use the slow-track passport application system; with one exception, all were areas with substantial Tibetan or Muslim populations. Human Rights Watch’s findings are based on analyses of internal regulations and interviews with Tibetans and others.

Chinese officials have denied that there is a ban on TAR residents’ access to passports, and assert that the process is simply slower because it is more complex.

There are increasing reports of similar restrictions on foreign travel by Uighurs and other predominantly Muslim residents of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). At least two Hui autonomous areas have also been denied access to the fast-track system.

The International Campaign for Tibet is also releasing a report today on the discriminatory policies facing Tibetans seeking to obtain passports. The report, “A Policy Alienating Tibetans,” gives the context for the Chinese authorities’ political agenda of undermining the Dalai Lama and seeking to assert their control over Tibetan people, and features new insights from discussions on social media.

China’s passport system in the TAR falls far short of international standards protecting the right to freedom of movement. The regulations are designed in a manner that discriminates on the basis of religion or ethnicity. The evidence available indicates that the regulations have an apparent discriminatory purpose, and that they are implemented in a manner that has an unlawful discriminatory effect.

The Chinese government should ensure the criteria and procedures for issuing passports are the same for all citizens, immediately implement fast-track processing in the TAR, XUAR, and other regions, and cease treating attendance at religious events or teachings abroad as unlawful activities, Human Rights Watch said.

“Chinese authorities seem to believe that systematically denying Tibetans’ rights to travel brings greater stability to the Tibet Autonomous Region,” Richardson said. “But it’s respect for human rights – including equal access to passports – that might begin to reduce Tibetans’ distrust of the government.”

Selected Quotes

“Border entry and exit administration structures within Public Security agencies should issue ordinary passports within 15 days of receiving the application materials. When a passport is not issued due to non-compliance, a formal written explanation should be provided, and the applicant should be informed of their right to pursue an administrative review of the application or to file a civil suit.”

– Regulations on passport processing in Shunyi (Beijing)

“Getting a passport is harder for a Tibetan than getting into heaven. This is one of those ‘preferential policies’ given to us Tibetans by [China’s] central government.”

– Post by a Tibetan blogger on a Chinese-language website, October 2012

“Why is it so hard for minority nationalities to apply for a passport? I’m from Qinghai, I’m Tibetan, and I work for a charity project. I don’t know what the policy is, but I’ve heard that we’ve been put among people of special interest by public security. We provide charitable assistance projects to impoverished areas, so why are we being regarded as terrorists? I’ve passed all the exams to go abroad for further study, but when I applied for a passport I need certificates like: certification from the court, certification from the procuracy, household registration certification, a seal from public security, and a seal from the Entry and Exit Administration, and then in the end I didn’t have certification from State Security so the application was spiked [Ch.: bei kazhu le]! I wonder if anyone else applying for a passport had to get all this certification? Can anyone help me think of what to do? Thank you!”

– An anonymous writer to an online Q&A site, August 10, 2010