Children working in dangerous conditions in Mali's gold mines don't stand a chance if companies shun rights initiative

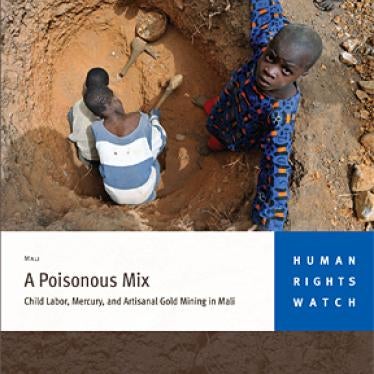

Aminata* is 11 and has never been to school. While other children learn to read, write and add up, Aminata works in an artisanal gold mine in Mali, west Africa. She spends her days panning ore for gold. To recover the gold, she mixes mercury with her bare hands into the ore and then burns the mercury-gold amalgam.

When I met Aminata in one of Mali's many artisanal (small-scale, often informal) mines, she told me she often suffers from backaches from hours of bending over. Asked about mercury, a highly toxic metal routinely used in the artisanal mining sector, she said: "I know mercury is dangerous, but I don't know [understand] how. I do not protect myself."

Aminata was one of dozens children I interviewed. These children work at the bottom of a long supply chain. In Mali, where hazardous child labour is common in artisanal gold mining, much of the gold is sold to traders in the capital, and then exported to Switzerland, Dubai, and elsewhere. One million children are estimated to work in artisanal mining worldwide, according to the International Labour Organisation. Many more children are exposed to environmental and health threats emanating from mining.

A new initiative, the Children's Rights and Business Principles, could bring hope for these children. The principles are being launched in London on Monday by Unicef, Save the Children, and the UN Global Compact and aim guide companies on how to better respect and support children's rights in the workplace and marketplace, as well as in the community. According to the principles, businesses should ensure that children are protected from child labour, violence and neglect, unsafe products and marketing, environmental impacts, or harmful consequences of land acquisition. Businesses are to be proactive champions for children's rights, for example, through their efforts to make essential products for children's development easily accessible.

The big question is: will companies go to the effort of implementing these principles? Or will they go on with business as usual?

In recent years, we have seen a flurry of voluntary initiatives to guide businesses, as well as action by businesses, for example, on global child health issues. In 2011, the UN adopted the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights; there are also various sector-specific initiatives and codes of conducts, including for resource extraction. But most of these initiatives are weak by design. They avoid independent monitoring to verify compliance and public reporting of the human rights impacts of businesses. Unfortunately, that is the same for the new Children's Rights and Business Principles. Whether children like Aminata will benefit from them depends purely on the will of individual companies to act – as well as on the will of governments to push in that direction.

In Mali, neither the government nor companies have done nearly enough yet to address the problem of child labour and mercury use in artisanal gold mining. And they can only make progress if they work on it together: Mali has strong laws on child labour but domestic implementation is poor.

Businesses that mine and trade Malian gold, as well as refiners and retailers sourcing gold from the country, should become actors in the fight for children's rights. They should take steps to ensure their own supply chain is child-labour free, and carry out sustainable and effective remediation programmes to address child labour, mercury pollution or other harmful effects on children. They should also urge the Malian government to take strong action to end child labour, improve access to education in mining areas, and address the problem of mercury.

Unfortunately, in Mali the mining chamber has denied the existence of hazardous child labour and the mining ministry is trying to present the problem as minimal. But there is good news, too. Some Malian businesses and government actors – as well as NGOs – are keen to respect and protect children's rights. The labour ministry has developed strong laws and policies on child labour, and the environment ministry is leading international efforts for a mercury reduction treaty.

The Children's Rights and Business Principles will not be a magic solution to the problems of children in Mali and around the world. But for those businesses that seek to contribute to positive change, the principles will provide useful guidance for the realisation of their human rights responsibilities. That way, one day Aminata can stop doing dangerous work and go to school instead.

*Aminata is a pseudonym to protect the girl's identity.

Juliane Kippenberg is a senior researcher in Human Rights Watch's children's rights division