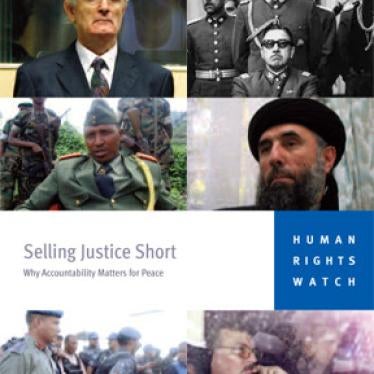

The thorny debate over whether pursuing justice for grave international crimes interferes with peace negotiations has intensified as the possibility of abusive national leaders being tried for grave human rights crimes has increased. In part this is because of the establishment of the International Criminal Court (ICC). The ICC is mandated to investigate and prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide in the course of ongoing conflicts. The call to suspend or ‘sequence' justice in exchange for a possible end to a conflict has arisen in conjunction with the court's work in Congo, Uganda, and most especially Darfur with the arrest warrant against a sitting head of state, Sudan's president Omar al-Bashir.

Some in the peace mediation field have argued that the possibility of prosecution poses a dangerous and unfortunate obstacle to their work. They fear that merely raising the specter of justice will bring an end to an already fragile peace process. Facing pressure to resolve an armed conflict, negotiators often feel pressed to push justice to one side.

For those acting in good faith, it is easy to understand the short term temptation to forego accountability for victims in exchange for an end to armed conflict, Sacrificing justice in the hope of securing peace is projected as a more realistic route to ending conflict and bringing about stability than holding perpetrators to account.

However, an analysis of the relevant facts documented in our recent report Selling Justice Short: Why Accountabilty Matters for Peace shows that out-of-hand dismissal of justice proves shortsighted. We believe that those who want to forgo justice need to consider the facts more carefully, many contradict oft-repeated assumptions. Because the consequences for people at risk are so great, decisions on these important issues need to be fully informed.

High Price

From the perspective of many victims of atrocities as well as human rights and international law standards, justice for the most serious crimes is a meaningful objective in its own right. Retributive justice through criminal trials is one means of respecting those who have suffered egregiously. Fair trials hold to account those accused and assert the rule of law in the most difficult circumstances.

But beyond the normative value of justice in its own right our research in many different conflict situations over twenty years has demonstrated that a decision to ignore atrocities and reinforce a culture of impunity may carry a high price.

While many factors influence the resumption of armed conflict, and we do not assert that impunity is the sole causal factor, we believe that the impact of justice is too often undervalued when weighing other important, but very different diplomatic and political objectives. In addition, our research indicates that the predicted negative consequences of pressing for accountability often do not come to pass.

Instead of impeding negotiations or a durable peace, remaining firm on the importance of justicecan yield short- and long-term benefits for peace. Indictments of abusive leaders and their resulting stigmatization can marginalize a suspected war criminal and may ultimately facilitate peace and stability.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina the indictment of Radovan Karadzic by the ICTY isolated him and prevented his participation in the 1995 Dayton peace talks. This contributed to Dayton's successful conclusion and the end of the war in Bosnia.

Similarly, the unsealing of the arrest warrant for President Charles Taylor at the opening of talks to end the Liberian civil war was ultimately helpful--and viewed as helpful--in moving negotiations forward. By delegitimizing Taylor both domestically and internationally, the indictment helped make clear that he would have to leave office, an issue that had been a potential sticking point in negotiations. He left Liberia's capital, Monrovia, a few months later. Since July 2008 and the request for an arrest warrant against Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir we have seen more strident objections calling not simply for a delay of justice, but an outright rejection of it. The Sudanese government has loudly and frequently pronounced that the warrant against al-Bashir would undermine peace talks between Khartoum and rebel forces in Darfur. However, the peace talks there have been paralyzed for a complex of factors - upcoming elections, a scheduled referendum on southern secession, to name a few - but the ICC process has been an easy scapegoat.

More recently, when Justice Richard Goldstone's UN report on alleged crimes in Gaza was issued, Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu brazenly declared that accountability for Gaza would destroy any prospect for peace in the conflict. The Prime Minister's statement conveniently overlooked the reality that there is hardly a credible peace process. The accompanying chorus of assent coming from governments that in other situations express support for accountability raises more than a whiff of a hypocritical double standard.

Further Abuses

Forgoing accountability, on the other hand, often does not result in the hoped-for benefits. Instead of putting a conflict to rest, an explicit amnesty that grants immunity for war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide may effectively sanction the commission of grave crimes without bringing the desired objective of peace. All too often a peace that is conditioned on impunity for these most serious crimes is not sustainable. Even worse, it sets a precedent of impunity for atrocities that encourages future abuses. Selling Justice Short documented that in Sierra Leone and Sudan.

In some situations, negotiators feel that turning a blind eye to crimes is not enough and that alleged war criminals must be granted official positions in order to persuade them to lay down their arms. However, we have seen that in places which have opted to incorporate such individuals into the government instead of holding them to account for their crimes or marginalising them, the price has been high.

Rather than achieving the hoped-for end of violence, Human Rights Watch has documented that in post-conflict situations, incorporating leaders with records of past abuse into the military or government has resulted in further abuses and has allowed lawlessness to persist or return. Recent events in Afghanistan and Democratic Republic of the Congo bear this out all too clearly. Including criminal suspects in government erodes public confidence in the new order by sending a message about tolerating such abuses and by further entrenching imounity.

International law and practice have evolved over the last fifteen years to the point where both peace and justice need to be the objectives of negotiations aimed at ending a conflict where the most serious crimes under international law have been committed. At the very least, peace agreements should not foreclose the possibility of justice at a later date.

As Archbishop Desmond Tutu has said, "As painful and inconvenient as justice may be, we have seen that the alternative-allowing accountability to fall by the wayside-is worse." Even decades after the crimes have occurred we have seen in places like Spain and Argentina that failing to address the past leaves open wounds that still demand attention.