Most travelers to Papua New Guinea have heard of the country's high crime rate. What they don't know is that many Papua New Guineans are as scared of the police as they are of common criminals.

International donors should be very concerned about this. Poor policing has aggravated the rampant law and order problems that continue to hurt Papua New Guinea's development and stability. While most donors have left policing assistance entirely up to Australia, for some issues, such as HIV/AIDS prevention, international organizations and other governments are chipping in. Police violence undermines this desperately needed assistance.

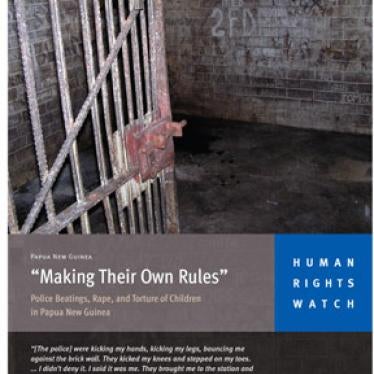

Severe beatings, rape and torture are widespread police practices. Teenage boys and young men-typed as raskols (members of criminal gangs)-are frequent targets, although even politicians' children have been beaten. Boys as young as 12 years old have described to me being whipped on the face with umbrella spokes, burned on the back with 8 to 10 inch sticks of cured tobacco, beaten with crowbars, slashed and shot. These tactics are not hidden-they are business as usual.

In the five areas of the country I have visited to investigate police treatment of children, almost everyone I interviewed who had been arrested said they were beaten. Many showed me fresh wounds and scars that were consistent with their stories. Almost everyone else volunteered having seen police officers beat someone. Doctors and nurses confirmed attending cases of people badly injured by police. Social workers, staff of juvenile detention centers, and others working with child detainees told me the vast majority of children they worked with were beaten. One man told me that police beat him and forced him to fight naked with other detainees in a Port Moresby police station when he was 16 or 17 years old. As he put it: "We thought it was their job and we just had to accept it."

Girls and women, as well as boys and men, report being raped in the bushes, in police cars, in police barracks and in police stations-often by more than one officer. (This is called "pack rape" or "lineup sex" in Papua New Guinea.) Because girls and women are rarely charged, tried and sentenced, their contact with the police is often not formally recognized. One woman said that in August 2004, police officers offered her a lift in their car but after she got in, they headed in the wrong direction. "I was trying to open the door and jump," she explained, "but they said, 'if you do, we'll shoot.' One tore my shirt, then two used me. I was scared because they were drunk with guns. Then they dropped me out of the car. I walked and I was crying then. I was sorry for my body."

Sexual abuse by police-especially targeting sex workers and men and boys engaged in homosexual conduct-may also be fueling Papua New Guinea's burgeoning AIDS epidemic. Experts believe that at least 80,000 people-3% to 4% of adults in the capital, the highest rate in the South Pacific-are living with HIV, at least half of whom are women and girls. They predict that infection rates by 2010 will easily reach 13% of adults.

Policing is not easy in Papua New Guinea. Crime rates are high, and the police by no means have a monopoly on violence. Other problems include tribal fighting in the highlands, and conflicts related to resource development and elections. The country's 5.6 million people speak more than 800 languages. The capital, Port Moresby, is not connected by road to any major city or town, and around 85% of Papua New Guineans live in rural areas where police presence and authority is limited. In a number of regions, police simply do not operate at all, reflectingthe weakness of Papua New Guinea's state institutions.

Grossly inadequate resources also impede effective policing. The country still has the same number of officers as it did 30 years ago when the population was half its current size. Regular officers are supplemented by reserve and auxiliary police who are particularly poorly trained and paid. Police often lack the most basic tools to do their jobs, such as pens, notebooks and gasoline. The situation is made worse by corruption, which in turn fuels the government's erratic payment of police salaries and benefits. The minister of police, who has frankly acknowledged the severity of police violence, told me that he is trying to improve police salaries and living conditions as a first step towards reforming the culture of law enforcement.

In the face of such challenges, even government studies conclude that police are failing to perform basic tasks. Instead, police rely on on-the-spot punishment and extracting confessions, including through torture.

Not surprisingly, these tactics are ineffective as well as abusive. A 2004 review of the police force commissioned by the minister of police found a serious and accelerating decline in the force's success in fighting crime. The chances of being arrested for committing a crime are low, and, according to statistics, even lower for more serious crimes. Communities outraged by police violence refuse to cooperate with criminal investigations. Some crime victims are afraid to approach the police even for help. Women and girls describe being asked for sex when they do. A woman told me that when she reported to a commander in July 2005, one of his men raped her. She did not go back. In a recent survey of residents in Port Moresby, more than half said they felt less safe when members of a mobile police squad were around than when they were not.

There is no question that reducing police use of torture, rape, and excessive force is necessary for better policing. But to achieve that, the Papua New Guinea government and its international friends have to change their approach. Any serious effort to stop police violence must include three key components: public repudiation of police violence by officials; criminal prosecution of perpetrators; and ongoing, independent monitoring of violence by law enforcement officers.

Given the critical role of international donors in funding the police sector in Papua New Guinea, a serious effort to eradicate police violence in Papua New Guinea will require a far more active role on the part of the international community, and not just by Australia. Although not unaware of the problem, donors have not prioritized police violence or devised a coordinated strategy to stop it.

Australia, from which Papua New Guinea has been independent since 1975, remains the most significant and influential donor, providing hundreds of millions for police assistance. Canberra has earmarked close to $378 million in development aid for the fiscal year 2005 to 2006.

In 2004, Papua New Guinea and Australia agreed to an Enhanced Cooperation Programme worth $618 million in new police funding, which deployed more than 200 Australian Federal Police to patrol with Papua New Guinea police in several cities, and provided more Australian technical advisors to the government. According to the minister of police, in the few months that the officers were deployed, people started reporting more crimes; many ordinary Papua New Guineans told me they felt safer then. But the Australian police were withdrawn in May 2005, following a Papua New Guinea Supreme Court ruling that found the immunity agreement for Australian police unconstitutional. In August, the governments agreed to a much-reduced plan to keep the technical advisors, to deploy more advisers on corruption, and to send back 30 Australian officers to provide training but not to patrol. This looks far too much like past police assistance, which, Australian officials admit, has had little or no effect on police violence. Indeed, in recent years things appear to have deteriorated. The minister of police's 2004 review concluded that "discipline is in a state of almost total collapse" and that without discipline being restored, additional police resources will have little effect.

Why has Australian assistance had so little effect on police violence up to this point? One of the most glaring reasons is near complete impunity for Papua New Guinean officers and commanders who participate in, order, or ignore violence. The police remain a powerful and independent institution run by the police commissioner; under the constitution even the minister for police has no power of command over the force. At present, there is almost no willingness on the part of the police to investigate or prosecute its members. According to the police's internal affairs directorate, responsible for public complaints against the force, no police officers were convicted of crimes and none were imprisoned in the first nine months of 2004. Although 38 officers were ordered dismissed during the same period (not all for violence), local stations often do not serve or enforce dismissal notices.

Moreover, internal police investigations rely on local officers who often have little interest in policing their colleagues. The head of internal investigations in AIotau in Milne Bay province, on the eastern end of mainland Papua New Guinea, explained how he handled a typical case. A 14-year-old boy claimed that police assaulted and robbed him, he said, but the boy could not name the officers. (Police often do not wear nametags.) "If he's really concerned about his case, he should come back and assist me with my investigation," the officer told me. "He gave all the work to me and went away and expects me to do the work. Then I see they're not concerned about the case, so I just sit down."

In some areas, high-ranking officers are to blame; it is especially difficult even for motivated local officers to investigate their commanders. For example, in Wewak, East Sepik province, individuals told me that the provincial police commander personally helped pull down a family's house after arresting the son for breaking and entering.

With little or no penalty for violators, and few incentives for good practices, training by Australia and others doesn't hold up on its own. Classroom theory by itself cannot compete with what officers learn on the job. One officer in the Eastern Highlands explained to a United Nations Children's Fund/NGO researcher in 2004: "New recruits get into these practices [using women and girls kept in custody for sex] having learned from those before them." These practices, he said, are "now a 'tradition' in the police force" and are "accepted as normal by most policemen." The police commissioner told me in September 2005 that more training is urgently needed. If so, he must be willing to hold his officers accountable for following it.

Another problem is the failure to address the overall institutional culture of policing methods that encourage strongarm tactics. As a UN staff member working closely with the police explained to me: "Training that has been developed... doesn't go to the heart of the issue-that it's okay to bash or rape someone. Police really believe in the notion that it's OK to burn down someone's house." Australia, which does not take a human-rights approach to development, has not specifically targeted human rights in the more than 2,000 workshops for police it has funded in the last five years, although officials say human-rights issues are addressed during instruction on other topics.

At present, government structures external to the police that might hold police accountable and provide victims with redress have not been effective in diminishing police violence. Many in the justice system, such as judges and magistrates, appear to ignore or accept police violence. Papua New Guinea's ombudsman's commission, while widely commended for taking on government corruption, has a small human-rights desk, but as of early September, the desk was not handling individual cases of police abuse. Despite extraordinary costs to the state, successful civil claims fail to deter police violence because they are not borne by the police force or guilty individual officers. Procedural barriers also prevent many victims from pursuing legitimate claims.

An independent monitoring body outside the police force is urgently needed. This could be an existing body such as the ombudsman's commission, and the minister of police is asking for a police ombudsman to be created within the commission. However, this would require providing the ombudsman's commission with the resources and power to conduct credible investigations, which must, in turn, result in prosecutions where warranted. There are periodic initiatives to create a humanrights commission, and a proposal to restart the process is being drafted. However, a human- rights commission is likely years away. Responsibility for police monitoring should be assigned to an existing body in the meantime, and international donors should support monitoring mechanisms. They should also consider providing assistance for the development of local human-rights groups with the capacity for independent monitoring of police violence and agencies that can provide services for victims.

There is a bright spot, however, in the juvenile-justice system that an intergovernmental agency, with the support of UNICEF, has been creating from scratch. Last year, the first juvenile courts opened, and the government adopted policies to divert children from detention and halt the current standard practice of detaining children with adults. On paper, these policies look good, officers have been trained, and donors have provided resources. However, the government must now implement these policies. A critical component-one that has yet to be addressed-will be stopping police violence against children.

Zama Coursen-Neff is senior researcher for the Children's Rights Division.