The crystal blue waters and bright, hot day begged for a jump in the surf. But my friend, a refugee from Ethiopia, just wouldn't go near the ocean. "I haven't gone swimming for years," he said, shaking his head sadly, "Ever since the regime tortured me when I was a student. They stuck my head in dirty water until I thought I would drown."

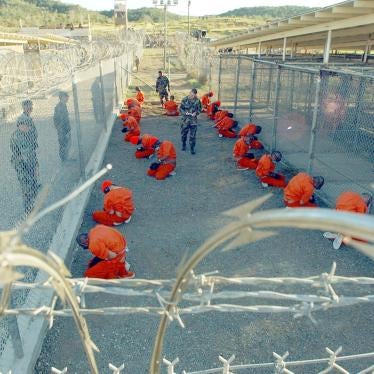

People tend to think of torture as physical. Torture conjures up images of the thumbscrews in the Tower of London and the rack during the Spanish Inquisition. Action movies to historical dramas focus on the infliction of severe physical pain that leave a body scarred, maimed or disfigured.

But torture is as likely to be mental as well as physical. The iconic photo of the Abu Ghraib torture scandal -- the hooded man on a box with outstretched arms -- was being subjected to psychological torture. The wires attached to his arms went nowhere -- he merely believed he would be subjected to electric shock.

The Convention Against Torture has long established torture as being either "physical or mental." The US anti-torture statute also adopts this definition. Even before the Geneva Conventions, the US military opposed psychological torture such as "waterboarding" -- pouring water into a detainee's nose and mouth until he believes, like my Ethiopian friend, he will drown. After World War II, the US military successfully prosecuted several Japanese soldiers who had subjected American prisoners to sleep deprivation and "waterboarding." And an American officer was court-martialed in 1968 for helping to "waterboard" a prisoner in Vietnam.

Distinguishing physical torture from mental torture is not always clear, which is one reason international law does not try to differentiate the two. However, in common understanding, three elements of psychological torture often get overlooked.

First, many coercive interrogation methods that are "only" psychological often cause lasting physical harm. According to the Physicians for Human Rights, psychological torture can have extremely destructive short and long-term physical health consequences, including memory impairment, headache and back pain, and severe depression with vegetative symptoms. For instance, sleep deprivation can result in hypertension and other cardiovascular disease, in addition to serious psychological problems.

Second, some methods of psychological torture have not traditionally been recognized as such. Placing a prisoner in indefinite solitary confinement, with little or no human contact for weeks or months or years, is likely to be far more destructive to an individual than a relatively brief infliction of physical pain, however cruel. Yet indefinite isolation is rarely labeled torture.

Third, the harm caused by mental torture, though unseen, can have a far more lasting impact on the individual than physical torture. The Minnesota-based Center for Victims of Torture says that people who have endured mock executions frequently relive their near-death experiences, inducing chronic fear and helplessness, and may feel as if they are already dead.

The US armed forces understood this in its new field manual on intelligence gathering. It specifically prohibits "waterboarding," mock executions and other primarily psychological methods of coercive interrogation.

Unfortunately, the Bush administration would still like to have us believe that mental torture isn't really torture. Last month July, the administration issued an executive order on the CIA's detention and interrogation program. Although there are some nice words about banning torture and other ill-treatment, the clarity and specificity of the army manual is missing, no doubt intentionally so.

The executive order tacitly endorses the CIA secret detention program, which allows indefinite incommunicado detention, itself a form of psychological abuse. There is no explicit prohibition of "waterboarding," a practice that the vice president and CIA director on down have refused to declare illegal. Administration officials have suggested that sleep deprivation remains permitted.

The Bush administration's recurring failure to openly and categorically ban torture deemed merely psychological places all Americans at risk. So long as these methods remain among the tools of CIA interrogators, the US will have no moral authority to complain about such techniques being used against Americans held abroad.

President Bush should rewrite the executive order to end CIA secret detentions and unlawful psychological as well as physical abuse. It is high time the administration stopped playing mind games with torture.