On Jan. 25 in Geneva, the Working Group on the UN Human Rights Council's Universal Periodic Review (UPR) held its hearing on Nepal. The UPR happens once every four years for each UN member state and makes recommendations for improving the human rights situation in the country.

The government was represented by Sujata Koirala, then the Deputy Prime Minister of Nepal. She painted a rosy picture of rights reforms across various sectors. The government has committed to considering a bill to criminalise torture. Drafts of transitional justice instruments, in the form of the Disappearances Act and the Truth and Reconciliation Act, have been widely discussed. The drafting committees have been open to suggestions and all new drafts, although still far from perfect, have seen amendments rectifying certain problems. There are still concerns that these transitional justice mechanisms might be used as venues to avoid prosecution, but at least the drafting committees have shown an interest in dialogue on the matter. Koirala, at pains to project Nepal as a human rights friendly government, stressed that Nepal adopts a "rights-based and holistic approach" regarding the protection of its citizens. She emphasised in particular that Nepal is committed to ending impunity.

This presentation may have sounded good in Geneva, but the reality in Nepal is much different. Human Rights Watch and other rights groups have consistently and repeatedly demonstrated that impunity remains an ongoing problem. During the conflict, we published report after report documenting extrajudicial killings, disappearances, torture, and arbitrary arrests (see ). We have provided more than enough evidence and information for the government to bring the killers and torturers to justice. Yet virtually no one has been held accountable. Impunity for both the Army and Maoists remains almost complete.

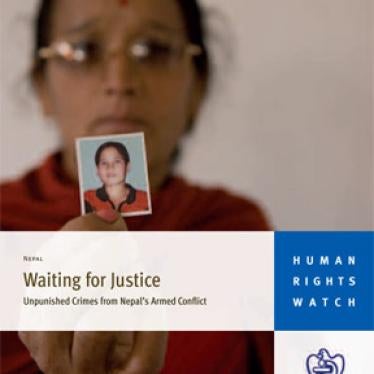

The main problem has been the refusal of the Army or Maoists, the two main perpetrators of human rights violations, to take action, or allow the police and courts to take action, against abusers in their ranks. Any small step forward in ending impunity has been met with denial or simple non-cooperation. When, through the intervention of OHCHR and pressure from rights groups, Major Niranjan Basnet was returned from peacekeeping duties to face allegations of his involvement in the torture and death of 15-year old Maina Sunuwar, the Army merely took him into its protective custody and publicly protested against his forced return. Yet in Geneva, where diplomats often don't have the facts at hand, Koirala asserted that the Nepal Army has a "zero-tolerance policy against all kinds of human rights abuses" and is a "disciplined" institution.

Impunity is so institutionalised that Supreme Court orders directing the Army and police to cooperate change nothing. In the case of Sarala Sapkota, for example, a May 2010 Supreme Court order to the Dhading District Police Office to investigate the case led to no action on the part of the police. A similar order from the Supreme Court into the case of Data Ram Timilsena from October 2010 has so far not been heeded. If Supreme Court orders can be blissfully ignored, lower court orders mean less than nothing.

Yet in Geneva, Koirala insisted that the judiciary is fiercely independent, without remarking on the fact that, whether independent or not, court orders are not worth the paper they are printed on and that the courts have become paper tigers whose rulings the government can wave around but in reality achieve nothing.

Efforts at reform are complicated by the lack of a stable government since the end of the civil war in 2006. Independent political analysts have long warned that the peace process in Nepal is floundering amidst bickering between the political parties as to the shape of the new constitution, already nearly one year delayed. The UCPN (Maoist), with the largest block of votes in Parliament, has effectively stalled any attempts by the other parties to forge a lasting cabinet. Calls by the Maoists for a unity government, with themselves at the helm, have met fierce resistance from the other parties. The creation of a nominal government last week has been beset with allegations of secret deals and backdoor handshakes that seriously affected its credibility within a matter of hours.

Yet this is a convenient excuse for the Army and Maoists. While they are in a seemingly endless political confrontation, they do share one trait: an aversion to holding abusers in their ranks accountable for human rights abuses.

Impunity is just part of the story that Koirala glossed over in Geneva. The traditionally disenfranchised caste and class groups, asylum seekers and refugees, women and other vulnerable populations continue to face systemic abuses. Torture, in spite of government denial, is still routinely used by security forces. Corruption fuels lawlessness, which in turn fuels rights abuses. Human Rights Watch recently documented extra-judicial executions, extortions, abductions and rape across a large part of the southern plains, a pattern of violations which the police effectively choose to ignore. The government claims to be in talks with 22 armed groups from the plains, but this seems to have had little impact on actually staunching the abuses in the region. Perhaps we can take some heart in the fact that Koirala stated that Nepal was committed to ending impunity. This at least signals an admission that impunity exists. But when will the government end its excuses and actually take action against abusers?

Perhaps it can start with Maina Sunuwar. This week marks the seventh anniversary of Maina's brutal killing in Army custody. Maina's case has long been held out to the government as an emblematic case over which it could, should it wished, take action to show that it is serious about justice for victims. The facts are hardly in dispute: the teenage girl, according to an Army court martial finding, died after torture while in Army custody. Those found guilty of her death were given cynically nominal sentences, which they had already served while in pre-trial detention and therefore were freed upon the court martial findings. Major Basnet admitted in his statement to the military that he had been present during Maina's torture, admitted that "she might have died due to water pouring [boarding], giving shocks etc," and admitted that he helped cover up Maina's death. This same Major continues to enjoy Army protection.

Nepal has to respond to the recommendations of the UPR Working Group in June 2011. It has time to bring Maina's killers to justice and to address some of the thousands of cases that have never even been investigated by the authorities. Yet up until now, reforms have been all talk and no action. Nepalis can be forgiven if they no longer trust pious words from politicians of all stripes that they are committed to justice and accountability. The government has a lot of work to do to gain their trust-and their votes at the next election.

Tej Thapa is a researcher in the Asia Division of Human Rights Watch.