I am standing in the corridor of the Palais de l'Europe in Strasbourg, home of the Council of Europe [13]'s Parliamentary Assembly, awaiting my next meeting to discuss the human rights situation in Azerbaijan. It is at this moment I'm handed an invitation from the Azerbaijani ambassador, requesting the pleasure of my company at a jazz concert marking the 10th anniversary of the country's accession to the Council of Europe.

It is an important anniversary, no doubt, but there's not much to celebrate. Membership in the Council of Europe, Europe's foremost human rights body, is a privilege which comes with a number of responsibilities, and this oil-rich country is failing to meet many of them. Azerbaijan has certainly reformed a number of laws in consultation with the Council of Europe, and even released some political prisoners, but many of its commitments have remained paper ones.

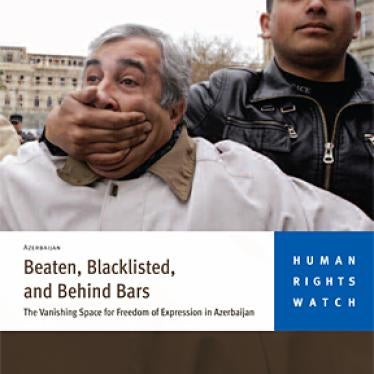

Azerbaijan continues to routinely flout the spirit of the Council of Europe. While supposedly committed to freedom of speech, not one opposition rally was sanctioned in Baku during the 2010 elections. Unsanctioned rallies such as the one in the photograph were dispersed with routine brutality.

One of Azerbaijan's promises, for example, was to guarantee freedom of expression and independence for journalists and the media. In reality, the government continues to be engaged in concerted efforts to limit freedom of expression. The authorities use criminal defamation and other laws and violent attacks to intimidate dissenting journalists and civil society activists, frightening many into silence. At least nine journalists have fled Azerbaijan in recent years [14], fearing repercussions for their work.

Senior Azerbaijani officials frequently bring criminal defamation charges against those who dare to criticize government policies or expose government corruption. It took three years and a European Court of Human Rights decision for the government to drop criminal defamation and trumped-up terrorism convictions against the outspoken editor Eynulla Fatullayev. [15] Despite the Court's call for his immediate release, Fatullayev remains in prison on new and bogus charges of drug possession.

The government paid compensation for damages - as the Court required - but to an account the authorities froze when they pressed terrorism charges against Fatullayev. Although the convictions were revoked, the account remains frozen, making the transfer appear cynical at best.

In another case, one of the most gratuitous applications of criminal defamation laws, Education Ministry officials brought charges against Alovsat Osmanli, [16] a mathematician, physicist and textbook author. His crime was that he publicly criticized the ministry in January 2010 for errors in math textbooks.

Another commitment by Azerbaijan was to ensure free and fair elections. The OSCE reports [17] from the November 2010 parliamentary elections indicated that Baku has a long way to go to meet this obligation. It should come as no surprise that only one opposition candidate won a seat on the 125-member legislative body, the Milli Mejlis [18].

The election also took place in a context of severely curtailed freedoms of expression and assembly. At no point during the entire election campaign, for example, did the government authorize an opposition rally in the centre of Baku. Police swiftly and often violently dispersed unauthorized protests, just as often arresting peaceful demonstrators and the journalists who were there to document police conduct. It is sadly symbolic that Azadlig ["Freedom"] Square - the central public square in Baku where opposition supporters used to gather - has now been turned into a parking lot.

Yet the Council of Europe welcomed [19] Azerbaijan's "peaceful" elections, with any criticism it had expressed in largely muted tones. Several officials at the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly tried to justify the approach in terms of maintaining cordiality with the Azerbaijani government. (I wonder, though, how they feel about the people of Azerbaijan?)

Yet another accession commitment concerned the release of political prisoners. The government did release some, but over the years it has arrested dozens more opposition supporters. Others still remain imprisoned on politically motivated charges. The Council of Europe's special rapporteur on political prisoners in Azerbaijan has four times requested [20] to visit the country, but the government has yet to cooperate with him.

At the ten year point of Azerbaijan's membership of the Council of Europe, it will certainly take more than just a jazz concert if the country is to prove its commitments to the principles that organization stands for. Releasing Fatullayev and decriminalizing dissent would certainly be steps in right direction. There would be no better way for Azerbaijan to celebrate its membership in Europe's foremost human rights body than by upholding its accession commitments.