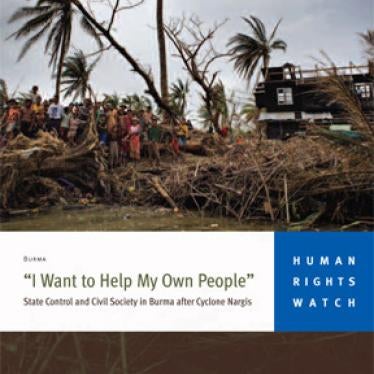

Cyclone Nargis struck southern Burma two years ago, on the night of May 2-3, 2008. It destroyed much of the Irrawaddy Delta, killed an estimated 140,000 people, and severely affected some 2.4 million others _ making it one of the worst natural disasters to strike Southeast Asia in generations.

Burma's ruling State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) delayed a major international relief effort, stranding aid and humanitarian workers for weeks in Bangkok, even as Burmese civil society responded admirably by rushing to the delta with whatever they could gather to assist survivors.

Why didn't the SPDC want too many foreigners in the country? One major reason was the cyclone threatened to derail a long-planned constitutional referendum, step four in the SPDC's ``Seven Step Roadmap to Disciplined Democracy''. Step Five is the holding of ``free and fair elections'', now scheduled to happen some time in 2010.

At roughly the same time that Cyclone Nargis was making landfall in Burma, the UN Security Council issued a presidential statement on May 2 calling on the Burmese government to ensure the referendum scheduled for May 10, 2008, would be free and fair.

``The Security Council underlines the need for the Government of Myanmar [Burma] to establish the conditions and create an atmosphere conducive to an inclusive and credible process, including the full participation of all political actors and respect for fundamental political freedoms.''

That was certainly wishful thinking. Since 1990, when the previous democratic elections delivered a clear win to the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD), the military junta had methodically set the stage for an ersatz democratic system. They rejected the 1990 election results and convened a National Convention in 1993 to write a new constitution. This convention met episodically, depending on security exigencies in Burma, prompting many to view it as a marker to buy time for the military to consolidate their rule.

It was effectively moribund for years, until the Road Map was released in 2003. This set out a process to complete the elections the military government had promised. During the 18 years from the 1990 elections to the constitutional referendum in 2009, political parties and their members were slowly squeezed into illegality, exile, prison or irrelevance.

The NLD was reduced to a defiant shell as its leader Aung San Suu Kyi was kept under house arrest and other party leaders were imprisoned. Ethnic opposition groups that reached ceasefire agreements with the government were frustrated by the SPDC's refusal to discuss political grievances yet feared armed retaliation by the Tatmadaw (Burma Army) if they breached the ceasefire pact.

Following demonstrations in Rangoon in August and September 2007, the SPDC weathered intense international outrage over its violent suppression of the monks, activists and ordinary citizens who marched for an end to military rule. By early 2008, Bur ma's prisons were overflowing with more than 2,100 political prisoners, representing a doubling of the number of political activists in jail from the previous year.

The text of the draft constitution was only formally released to the public in limited printings in March 2008, two months before the referendum. The constitution is replete with repressive provisions _ reserving seats for serving military officers (one-quarter in the lower house of parliament, one-third for the upper house), providing sweeping powers for the Tatmadaw, including control over key ministries and immunity from civilian prosecution, and setting out provisions to limit basic rights of citizens.

SPDC censorship and limitations on access severely hampered Burmese and foreign media trying to cover the referendum, compounding the limited access to information on the process available to the average citizen.

State-controlled media was heavy-handed, carrying incessant propaganda exhorting citizens to vote for the new constitution. Billboards erected throughout urban areas proclaimed: ``Let's approve the Constitution to shape our future by ourselves''; ``To approve the State Constitution is a national duty of the entire people today''; ``Let's cast `Yes' vote in the national interest''; ``Democracy cannot be achieved by anarchism or violence, but by the Constitution''.

In one of the only public opinion polls conducted ahead of the elections, Burma News International (BNI), a consortium of exiled media organisations, interviewed more than 2,000 people throughout Burma in April 2008 to gauge their responses to the referendum. The poll found that 83% of eligible voters planned to cast votes, with 64% saying they intended to vote no. A majority, 76%, claimed they would vote based on their conscience, not just coercion by the authorities. But 69% of respondents said they did not know what was in the constitution. There was no domestic or international election monitoring body permitted to observe the referendum.

One week after Cyclone Nargis hit, the first stage of the referendum was held throughout the country on May 8, in a total of 278 out of 325 townships in Burma. Polling in the 47 townships (40 in the Rangoon division and seven in the Irrawaddy division) badly affected by the cyclone was postponed to May 24. The SPDC's Commission for Holding the Referendum reported the total population in Burma was 57.5 million and people over the age of 18 and eligible to vote numbered 27.4 million. Yet where these figures came from is unclear since Burma has not conducted a nationwide census since 1983 and the SPDC does not control sizeable areas of the borderlands where civil war still simmers.

The repressive local government machinery of the Burmese state was responsible for ensuring a referendum result called for by the SPDC's generals and they left nothing to chance. The Village Peace and Development Council (VPDC), or Ya Ya Ka, and local military units were instructed to produce the right result by top military officials only concerned with a result, not a process. Local officials, cadres from the USDA, the government-backed mass movement, representatives of the Auxiliary Fire Brigade and Myanmar Red Cross Society, and military and police personnel either forced people to vote, or collected name lists of household and small community members that were all then fraudulently cast as ``yes'' votes by the referendum officials. It's one of the fundamentals of the SPDC's repressive rule _ construct a system where popular fear to defy the military is augmented through overlapping mobilisation of military, police and government-controlled social organisations to ensure obedience to the SPDC's dictates.

Burmese citizens from cyclone-affected areas interviewed by Human Rights Watch in the past several months remembered how the referendum process further complicated their desperate efforts to recover from the cyclone. While few overt cases of intimidation or threats were reported, many people described how the entire organisation of the referendum was coercive, and distracted from basic concerns of survival.

Htar Htar Yi, a 36-year-old woman from Laputta township in the delta, said the referendum process was more restrictive than the 1990 elections in which she voted as an 18-year-old. ``I experienced voting in 1990. Then I could vote freely as I liked, but this time was very different. We had no freedom to vote. I did not give any vote. The village authorities collected names of all family members for voting. I told a village official that I wanted to vote as I liked but he said he had already voted for us. We have no right to speak out because we are living under their power. They made all votes from the village for them [the SPDC].''

Sein Win, a Ya Ya Ka head in Dedaye township, arranged his village's vote on May 24, by turning it into a raffle to conceal that the whole process was rigged _ prizes such as instant noodles and nails were handed out to people who came forward and voted ``yes''. ``People from our village don't know what the constitution is. It's good that they don't know. If they knew, that would be a problem. If our villagers voted `yes', we might be favoured by the government while distributing assistance,'' Sein Win remembers.

Kyin Maung, a 57-year-old man from Dagon, near Rangoon, said that despite the low turnout at the polling stations in his area on May 24, a high percentage of residents had their votes tabulated. ``The referendum was arranged by the Ya Ya Ka and USDA. They set up polling stations in the schools and monasteries. The USDA members, women's groups [MWAF], firemen and Red Cross members were there to supervise the referendum. I went to vote at the polling station. In some areas in my town, local authorities arranged advance ballots on behalf of voters and later they told people that there was no need to go to the polling station as they did it all for them. About 75% of voting in our area was like that. Only about 25% voted individually,'' Kyin Maung said.

In some cases, the authorities included the dead or missing from the cyclone in the vote count. May Khin, a 45-year-old woman from an isolated village in Laputta, whose daughter went missing in the cyclone, said she allowed authorities to take the names of both her and her daughter as instructed. ``Soon after Nargis, the authorities came and collected names from every household. I told them that I don't know whether my daughter is alive or dead. But they took both of our names. The Ya Ya Ka arranged polling stations in the village school. Not many people went to vote because most of us had given the advance ballot. If they asked me to vote, I have to vote. In order to get food and a place to stay, we had to vote.'' Ma Mei Mei, a young woman from Dedaye township said the same: ``We were told just to cast a `yes' vote. At the time, people were struggling hard to survive. We just did what we were told.''

A Christian pastor from Rangoon who was supporting church members in Pathien township said that authorities were using displaced survivor facilities to gather names. ``When the people came into the camps the authorities registered them, but it was also a `yes' vote for the referendum. Many people refused to go to the new camps, so they had to hide in other people's houses.''

In one of the starkest examples of the twisted process, the authorities forced political prisoners at Insein prison in Rangoon to vote, in direct contravention of the Referendum Law (Chapter V, Preparing Voting Rolls, section 11, (d), 3), which states that one category of citizen not to be included in the voting rolls are ``persons serving prison terms, having been convicted under order or sentence of a court for any sentence''.

Htet Aung, a dissident imprisoned in Insein at the time said: ``We were asked to vote three or four days in advance of the referendum. The prison authorities read the guidelines and explained to us how to vote. They collected ballots at every room [cell]. We had to mark the ballot in front of them while they were taking photos and video of us. They could see clearly what we marked on the ballots.''

At the end of May, the government announced the final national results _ a 92% nationwide ``yes'' vote resulting from a 98% voter turnout. The SPDC claimed that 99.07% of the voters eligible to vote on May 8 actually cast ballots. In cyclone affected areas that voted on May 24, the SPDC reported that 93.44% of the population cast votes _ an unbelievable number given the challenges to survive that people were facing just two weeks after the cyclone _ and announced 92.93% in the cyclone jlaffected regions voted in favour, versus 5.99% who voted ``no''.

The way the SPDC conducted the referendum in the aftermath of Nargis is instructive of how the elections will likely be conducted later in 2010, within a nation-wide environment of intimidation constructed to ensure the right result for the military government. But there are also important differences. The referendum was a simple yes or no vote on a constitution most people in Burma had never read. The forthcoming elections will entail voting for candidates to a national bi-cameral parliament, and to provincial-level assemblies.

The voting process will be more complex, the choices more varied and campaigning more widespread.

Yet just as the SPDC ruthlessly and single-mindedly pushed through its referendum just three weeks after Cyclone Nargis, continuing an electoral charade while hundreds of thousands of survivors waited desperately for assistance, the broad results of the 2010 elections are already pre-determined: Burma will have a civilian front parliament for continued military rule. A slightly more sophisticated, or less brutally inept, authoritarian system, but one no less ruthless or sinister.

David Scott Mathieson is Burma researcher for Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch's report, `I Want to Help My Own People: State Control and Civil Society in Burma After Cyclone Nargis', was published on April 29.