I spoke recently with a young woman who was raped two years ago and had been told that her case had been closed, without the physical evidence that might have led to prosecution of her rapist ever being tested. She said she still woke up most days hoping the police would change their minds. "But," she said, "it's so stupid for me to hope for justice, isn't it?"

The news in recent weeks has been filled with reports about rape, all of it pointed to one truth: Even officials who are supposed to investigate and prosecute rape would rather not deal with it.

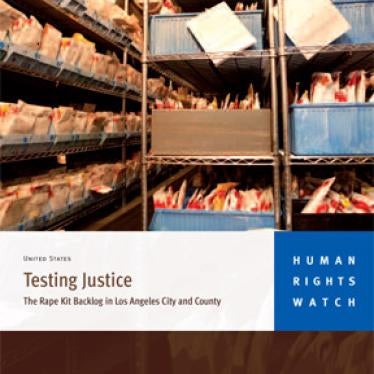

We read about the 11 women's bodies found at the home of a convicted sex offender in Cleveland-found years after the reports started coming in of frightening events taking place there. "CBS Evening News" reported finding at least 20,000 sets of physical evidence in rape cases sitting untested in police storage facilities throughout the country.

Then the National Institute of Justice released a report that found evidence from rape cases is less likely than evidence from other violent crimes to be sent forward for crime-lab testing.

Testing the physical evidence in a rape case, known as a rape kit, is very important. It can identify an unknown rapist, confirm the presence of a known suspect, affirm the victim's version of events or exonerate an innocent defendant. The prosecution and conviction rates for rape cases have risen considerably in jurisdictions that have made a commitment to test every kit.

Every year, nearly 200,000 people report to the police that they have been raped. Almost all are asked to submit to the invasive and sometimes traumatic process of having DNA evidence collected from their bodies. They assume this will help catch their rapist. They are often wrong. Thousands of kits throughout the United States remain untested, and the arrest rate for rape is less than 25 percent of reported case.

The hopeful news is that even in the midst of all the activity around health care and Afghanistan, Congress is turning its attention to the problem. Sens. Al Franken, Minnesota Democrat; Charles E. Grassley, Iowa Republican; Dianne Feinstein, California Democrat; and Orrin G. Hatch, Utah Republican, recently introduced the Justice for Survivors of Sexual Assault Act of 2009. The bipartisan legislation would require the federal government to collect data on untested rape kits in police and crime-lab storage facilities and require jurisdictions that get funds from federal DNA funding programs to make testing the rape kits a priority.

A companion bill was introduced in the House of Representatives on Nov. 20 by Rep. Carolyn B. Maloney, New York Democrat, and Rep. Dean Heller, Nevada Republican. We hope the House Judiciary Committee will hold hearings on the bill to focus on the need for action on this issue.

In 2004, Congress passed the Debbie Smith Act, named after a rape victim whose case was adversely affected by the rape-kit backlog, to provide money to states for rape-kit testing. But because the bill allows jurisdictions to use the money for any DNA testing, it often is not used to test rape kits. In fact, some grantees have not even used their funding even though they have large backlogs.

In March 2009, reporting from Human Rights Watch revealed a backlog of more than 12,500 untested rape kits in Los Angeles Police and Sheriff department facilities, though those agencies had received nearly $8 million in Debbie Smith Act funds from 2005 to 2008.

In October, the Detroit Police Department reported it had as many as 10,000 untested rape kits; it has never applied for Debbie Smith Act funds. "CBS Evening News" found 5,100 untested kits in San Antonio and 1,100 in Albuquerque, N.M. A dozen major cities told CBS they have no idea how many untested rape kits they have.

Without federal or state laws requiring law enforcement agencies to account for untested rape kits, there are no current comprehensive data on the number of untested kits in the United States.

The rape-kit backlog is clearly a national problem that requires a strong federal response. Untested rape kits represent lost justice for rape victims.

The proposed new law would require states receiving Debbie Smith Act funds to develop and carry out a plan to eliminate their rape-kit backlogs, including reducing any backlog by 50 percent within two years. The bill would use financial incentives to encourage state and local governments to take aggressive steps to eliminate backlogs and require every jurisdiction receiving certain grants to report annually on its untested rape kits.

No victim should be made to feel that hoping for justice is stupid or in vain. The Justice for Survivors of Sexual Assault Act of 2009 would go a long way toward ensuring that law enforcement agencies use all the tools at their disposal to investigate rape.

The evidence in thousands and thousands of cases sits untested in police storage facilities while victims wait for justice.